Excising the Cancer in Our Institutions

We need to start thinking about how we are going to separate the sheep from the wolves in sheep's clothing.

One thing that was clear from Attorney General Pam Bondi’s testimony temper tantrum in front of the House Judiciary Committee this week is that the Justice Department as we knew it is gone. Over. Kaput. Buh-bye. I had predicted as much with the FBI last August, but I thought the lawyers might last a bit longer. Nope. The Justice Department’s workforce is now so drained that it’s advertising for lawyers on X — and the main criteria appears to be that you support Trump:

Just as context, working for the Justice Department used to be one of the most competitive, prestigious jobs you could get as a lawyer. Only a select few joined the entry-level honors program right out of law school. Most people — even top law students coming out of top law schools — spent several years working for law firms before vying for highly coveted spots at U.S. Attorney’s offices across the country or at Main Justice.

Now you send a DM on X to some guy named Chad.

The FBI and the Justice Department are the two agencies I pay the closest attention to, but this same “hollowing out” — through a combination of mass firings and/or resignations — has happened across our government. For the agencies that weren’t eliminated entirely, like USAID, the ranks are slowly being replaced by Trump loyalists, who must make it clear to whoever is hiring them that their loyalty is to the President, not the Constitution. That “loyalty test” is becoming obvious when we see journalists being arrested, search warrants executed against state election facilities, and the attorney general acting like a mean girl on crack in the halls of Congress. To use John Dean’s famous phrase, there’s a cancer in the presidency — and it’s now spread to every corner of our federal government.

There is obviously going to have to be a reconstruction of sorts to rebuild the institutions that have been hobbled, decimated, and corrupted (and a deconstruction, in the case of the White House ballroom). But this will present a dilemma regarding how to deal with the people who will be currently serving as civil servants when Trump leaves power. How do you separate those who were there when he took office and stuck it out, believing they could do some good (or perhaps cancel out the bad) until things returned to “normal,” and the loyalists hired by Chad and others like him? Are there gradations in between that should matter?

One possibility to address this problem is to just do exactly what the Trump administration did: mass firings. Purge everyone, and then hire again from scratch. This has a nice “clean slate” feel to it, but it doesn’t exactly help build stability. For one thing, it looks like a tit-for-tat, and in doing so creates a norm that every administration that comes in can just purge everyone in the federal civicl service and start over. (It’s hard to create a bright line rule that differentiates “righteous” purges from ones that aren’t.) Another possibility is to not necessarily fire everyone, but make them reapply, so that they get reassessed — perhaps with a full background check or whatever other kind of vetting was normally done that got jettisoned by the Trump administration. But that is slow and cumbersome, and it also potentially allows people who were complicit in really bad things to slip through the cracks and stay.

I’ve been thinking a lot about another approach I have come across in my book research that was taken in the Allied occupation zone after World War II, during the process of denazification. The Allies faced a very difficult problem, which was how to identify various levels of culpability and provide commensurate consequences — but to do so in a way that preserved democratic values of transparency, due process, and fairness.

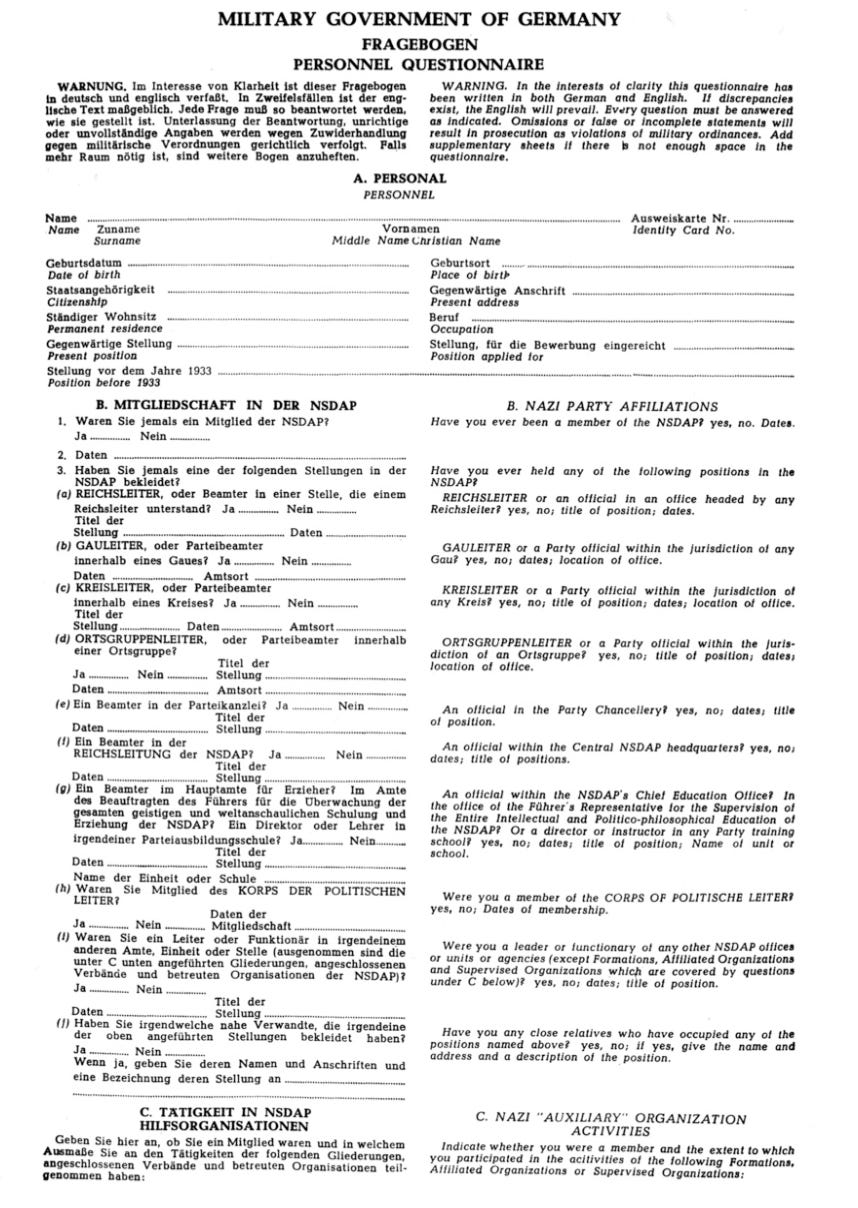

Their answer was to create Allied Control Council Directive 38, a sorting system based on questionnaires (Fragebogen) that assessed an individual’s involvement with the Nazi regime. These questionnaires inquired about personal history; secondary and higher education; professional and trade training; record of full time employment, experience and military service; membership and role in all types of organizations before and after the Hitler regime, especially the Nazi Party and its organizations; writings and speeches since 1923; income and assets since 1 January 1931; and travel and residence abroad.

Based on the answers to these questions, Germans were divided into five categories:

“Major Offenders” (Hauptschuldige): these included senior Nazi leaders, SS leadership, high-level party officials, and those directly responsible for major crimes;

“Offenders” (Belastete): individuals defined as “activists,” “militarists,” and “profiteers” who exercised authority, engaged in brutal acts, and materially benefited from or enforced Nazi policies;

“Lesser Offenders” (Minderbelastete): opportunistic individuals who joined the party for career, pressure, or social status. They either participated or cooperated with the regime but lacked decision-making power, or were akin to Offenders but “without having manifested despicable or brutal conduct”;

“Followers” (Mitläufer): passive participants, often party members in name only and people who went along without enthusiasm or initiative. (Mitläufer literally translates as “one who runs along with others”); and finally

“Exonerated Persons” (Entlastete): those who resisted, were coerced, or actively opposed the regime and suffered disadvantages as a result.

The law also established a special German tribunals (Spruchkammern) in the U.S. occupation zone to adjudicate the individuals once their level of culpability was determined from the questionnaire. One thing I found interesting was that the burden was on the individual to prove their innocence, rather than for the tribunal to prove their guilt, which reflected the presumption that everyone was complicit unless they could demonstrate otherwise.

The Frageboden/Spruchkammern system became increasingly ineffective as a sorting mechanism, partly because of the sheer volume of people that had to be processed (approximately 13.7 million Germans over the age of 18 were processed in the U.S. zone alone), and partly because the judges who were adjudicating the system were themselves complicit to some degree in the regime as well.

But cleaning up the federal government — and the civil service more specifically — could be a much more manageable task in this regard, one that might be more amenable to this type of “sorting.” One thing is for sure: There is no way to go back to “business as usual” when this is all over. Some deep surgery will be needed before we can return our governing institutions to a remotely healthy state.