Saturday, February 28, 2026

SECRETARY CLINTON'S OPENING STATEMENT TO THE HOUSE OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM COMMITTEE

SECRETARY CLINTON'S OPENING STATEMENT TO THE HOUSE OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT

Trump’s Attack on Iran Is Reckless

Trump’s Attack on

Iran Is Reckless

Feb. 28, 2026

In his 2024 presidential

campaign, Donald Trump promised voters that he would end wars, not start them.

Over the past year, he has instead ordered military strikes in seven nations.

His appetite for military intervention grows with the eating.

Now he has ordered a new

attack against the Islamic Republic of Iran, in cooperation with Israel, and

Mr. Trump said it would be much more extensive than the targeted bombing of

nuclear facilities in June. Yet he started this war without explaining to the

American people and the world why he was doing so. Nor has he involved

Congress, which the Constitution grants the sole power to declare war. He

instead posted a video at 2:30 a.m. Eastern on Saturday,

shortly after bombing began, in which he said that Iran presented “imminent

threats” and called for the overthrow of its government. His rationale is dubious, and making his case by video in the middle

of the night is unacceptable.

Among his justifications

is the elimination of Iran’s nuclear program, which is a worthy goal. But Mr.

Trump declared that program “obliterated” by the strike in June, a claim belied

by both U.S. intelligence and this new attack. The contradiction underscores

how little regard he has for his duty to tell the truth when committing

American armed forces to battle. It also shows how little faith American

citizens should place in his assurances about the goals and results of his

growing list of military adventures.

Mr. Trump’s approach to Iran is

reckless. His goals are ill-defined. He has failed to line up the international

and domestic support that would be necessary to maximize the chances of a

successful outcome. He has disregarded both domestic and international law for

warfare.

The Iranian regime, to be clear, deserves no sympathy. It has wrought misery since its revolution 47

years ago — on its own people, on its neighbors and around the world. It massacred thousands of protesters this year. It

imprisons and executes political dissidents. It oppresses women, L.G.B.T.Q.

people and religious minorities. Its leaders have impoverished their own

citizens while corruptly enriching themselves. They have proclaimed “Death to

America” since coming to power and killed hundreds of U.S. service members in

the region, as well as bankrolled terrorism that has killed civilians in the

Middle East and as far away as Argentina.

Iran’s government

presents a distinct threat because it combines this murderous ideology with

nuclear ambitions. Iran has repeatedly defied international inspectors over the

years. Since the June attack, the government has shown signs of restarting its pursuit of nuclear weapons

technology. American presidents of both parties have rightly made a commitment

to prevent Tehran from getting a bomb.

We recognize that

fulfilling this commitment could justify military action at some point. For one

thing, the consequences of allowing Iran to follow the path of North Korea —

and acquire nuclear weapons after years of exploiting international patience — are too great.

For another, the costs of confronting Iran over its nuclear program look less

imposing than they once did.

Iran, as David Sanger of

The Times recently explained, “is going through a period of

remarkable military, economic and political weakness.” Since the Oct. 7, 2023,

attacks, Israel has reduced the threats from Hamas and Hezbollah (two of Iran’s

terrorist proxies), attacked Iran directly and, with help from allies, mostly

repelled its response. The new recognition of Iran’s limitations helped give

rebels in Syria the confidence to march on Damascus and oust the horrific Assad

regime, a longtime Iranian ally. Iran’s government did almost nothing to intervene. This recent

history demonstrates that military action, for all its awful costs, can have

positive consequences.

A responsible American president could

make a plausible argument for further action against Iran. The core of this

argument would need to be a clear explanation of the strategy, as well as the

justification for attacking now, even though Iran does not appear close to having a nuclear weapon.

This strategy would involve a promise to seek approval from Congress and to

collaborate with international allies.

Mr. Trump is not even

attempting this approach. He is telling the American people and the world that

he expects their blind trust. He has not earned that trust.

He instead treats allies

with disdain. He lies constantly, including about the results of the June

attack on Iran. He has failed to live up to his own promises for solving other

crises in Ukraine, Gaza and Venezuela. He has fired senior military leaders for failing to show

fealty to his political whims. When his appointees make outrageous mistakes —

such as Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth sharing advanced details of

a military attack on the Houthis, an Iranian-backed group, on an unsecured

group chat — Mr. Trump shields them from accountability. His administration

appears to have violated international law by, among other things, disguising a military plane as a civilian plane and shooting two defenseless sailors who survived an initial attack.

A responsible approach

would also involve a detailed conversation with the American people about the

risks. Iran remains a heavily militarized country. Its medium-range

missiles may have failed to do much damage to Israel last year, but it

maintains many short-range missiles that could overwhelm any defense system and

hit Saudi Arabia, Qatar and other nearby countries. Mr. Trump did acknowledge

this in his overnight video, saying, “The lives of courageous American heroes

may be lost and we may have casualties.”

He should have had the

courage to say so in his State of the Union address on Tuesday, among other

settings. When a president asks American troops and diplomats to risk their

lives, he should not be coy about it.

Recognizing Mr. Trump’s irresponsibility, some members of Congress have taken steps to constrain him

on Iran. In the House, Representatives Ro Khanna, Democrat of California, and

Thomas Massie, Republican of Kentucky, have proposed a resolution meant

to prevent Mr. Trump from starting a war without congressional approval. The

resolution makes clear that Congress has not authorized an attack on Iran and

demands the withdrawal of American troops within 60 days. Senator Tim Kaine,

Democrat of Virginia, and Senator Rand Paul, Republican of Kentucky, are

sponsoring a similar measure in their chamber. The start of hostilities should

not dissuade legislators from passing these bills. A robust assertion of

authority by Congress is the best way to constrain the president.

Mr. Trump’s failure to

articulate a strategy for this attack has created shocking levels of

uncertainty about it. He has called for regime change and offered no sense of why the world should expect

this campaign to end better than the 21st-century attempts at regime change in

Iraq and Afghanistan. Those wars toppled governments but understandably soured

the American public on open-ended military operations of uncertain national

interest, and they embittered the troops who loyally served in them.

Now that the military

operation has begun, we wish above all for the safety of the American troops

charged with conducting it and for the well-being of the many innocent Iranians

who have long suffered under their brutal government. We lament that Mr. Trump

is not treating war as the grave matter that it is.

Friday, February 27, 2026

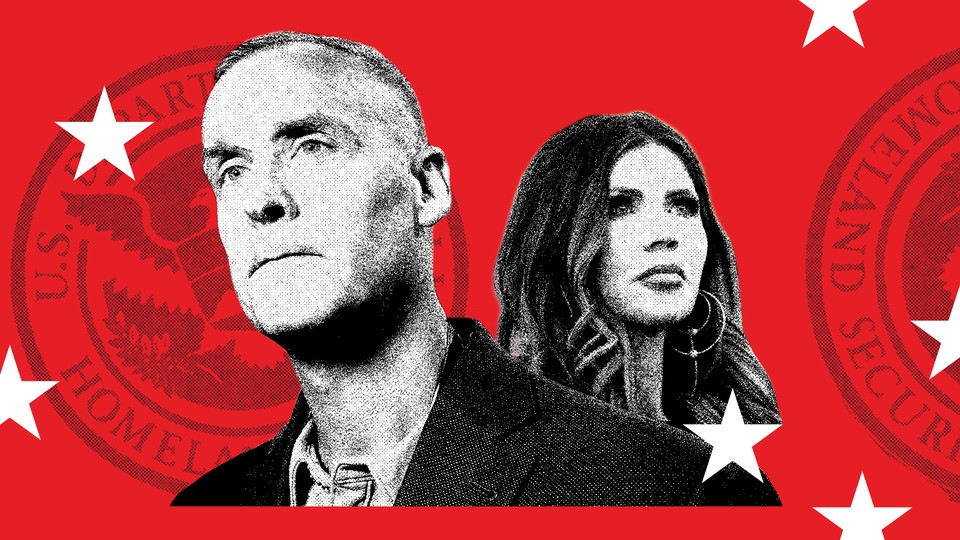

The First Couple of a Dysfunctional DHS

The First Couple of a Dysfunctional DHS

A forthcoming book reveals new details about Kristi Noem and Corey Lewandowski.

On a winter night last year, shortly after Donald Trump was sworn into office, senior officials at the Department of Homeland Security assembled discreetly at a private home in Washington, D.C., to discuss what they saw as a gathering crisis inside the agency: the relationship between their new boss, Kristi Noem, and Corey Lewandowski, her adviser, enforcer, and rumored boyfriend.

The officials were under enormous pressure. Trump had recaptured the presidency amid a popular backlash against illegal immigration, and had promised a shock-and-awe program of mass deportations once he returned to power. Now DHS—conceived after 9/11 to protect the country from terrorist attacks—was being ordered to shift its focus and resources toward delivering on the president’s campaign pledge. This project, already controversial and logistically fraught, was being complicated by Lewandowski—a menacing, omnipresent operator who had no experience in immigration enforcement, but who was nonetheless quickly consolidating power at the agency. The officials had gathered that night to map the ways his relationship with Noem could destabilize the department. The conversation ran six hours.

The secret meeting, which has not been previously reported, is described in Undue Process: The Inside Story of Trump’s Mass Deportation Program, a forthcoming book by the NBC News reporter Julia Ainsley. The book is set to be published in early May, but The Atlantic obtained portions of it early.

The book, based on extensive reporting, depicts the Department of Homeland Security as a dysfunctional fiefdom in Trump’s Washington empire—tasked with carrying out the most aggressive immigration crackdown in U.S. history even as the agency’s internal culture is warped by the relationship between an ambitious, attention-thirsty secretary and her domineering right-hand man and alleged paramour. In Ainsley’s account, Lewandowski is involved in nearly every aspect of the agency: who gets heard in meetings, what information reaches Noem’s desk, which contractors get hired, and even what kind of detention facilities are built to hold arrested migrants.

Michael Scherer: The buzz in Kristi Noem’s home state

Noem and Lewandowski, both of whom are married with children, have denied a romantic relationship. “It’s bullshit,” Lewandowski told The Atlantic in October. A spokesperson for DHS said, “This Department doesn’t waste time with salacious, baseless gossip.”

But their rumored affair has been widely treated as an open secret in Washington—first whispered about in political and media circles, then chronicled in tabloids such as the Daily Mail, and, more recently, making its way into The Wall Street Journal, which reported that the pair flies around the country together in a luxury 737 with a private cabin in the back, and that the president frequently asks about the relationship. In Undue Process, Ainsley quotes unnamed officials describing the alleged affair as common knowledge. “They don’t hide it,” says one Customs and Border Protection official who interacted with them regularly. A member of Trump’s transition team, Ainsley writes, put it more crassly to her in January 2025: “Oh yeah, they’re still fucking.”

The reported affair has caused tension with the West Wing: When Noem tried to install Lewandowski as her chief of staff, the White House vetoed the move. Rumors about their relationship were already circulating too widely—and Stephen Miller, Trump’s deputy chief of staff and most influential immigration hawk, was personally repelled by their apparent infidelity, according to Ainsley’s book. (Miller, Ainsley writes, is a “hard-liner when it comes to monogamy in marriage,” though a quick survey of the White House org chart surfaces at least one exception to his purported no-adulterers rule.) When a CBP official sought Miller’s advice on how to navigate the new terrain at DHS, Ainsley writes, he warned, “Stay away from Corey.” Reached for comment, a White House official disputed this account, saying “Stephen has never had any conversations about these rumors nor expressed any thoughts or feelings on them” and “Stephen has never told anyone to stay away from Corey.”

Instead, Lewandowski was hired as a “special government employee,” similar to Elon Musk’s arrangement as the head of DOGE. The designation is supposed to cap government work at 130 days a year, but according to Ainsley, Lewandowski seemed to disregard the rule. Inside DHS headquarters, he began referring to himself as “chief adviser” to the secretary. (According to the DHS spokesperson, Lewandowski worked 115 days last year as a special government employee.)

Lewandowski was a relative no-name in Republican politics when he was hired in 2015 to serve as Trump’s first campaign manager. He developed a reputation for vindictiveness and bullying; his brief tenure was marked by multiple physical confrontations with reporters and protesters. He was also accused of making sexually suggestive comments and unwanted romantic advances toward female journalists covering the 2016 campaign. (Lewandowski denied these allegations at the time.)

But his loyalty earned him a permanent place in Trump’s orbit, which Lewandowski has used in recent years to advance Noem’s political career—introducing her to key Trump-world figures and shaping her public image. Noem’s rise from governor of South Dakota to MAGA political celebrity was also abetted by her own refashioning. As Ainsley writes, Noem underwent an extensive physical transformation to conform to a certain MAGA aesthetic—including dental surgery and other apparent cosmetic enhancements—and, by 2024, she was traveling with a personal makeup artist. (The DHS spokesperson noted that Noem has not traveled with a makeup artist as secretary.)

She also has a flair for the theatrical. Shortly after she was installed in the Cabinet, she attended a pre-raid briefing for ICE officers in New York City. As career officials looked on in bewilderment, Noem walked onstage—in TV-ready makeup, coiffed curls, and a Kevlar vest—to a country song by Trace Adkins called “Hot Mama.” (“And you’re one hot mama / You turn me on. Let’s turn it up, and turn this room, into a sauna.”) The surreal spectacle helped earn Noem the nickname “ICE Barbie.”

Trump had reportedly considered tapping Noem to be his running mate in 2024. But her name was crossed off the short list after she disclosed in a memoir that she had shot an “untrainable” family dog years earlier. The story prompted widespread outrage and ridicule, and many observers assumed it sank her prospects of an administration post. But Ainsley reports that Trump actually saw this particular biographical detail as an asset in his homeland-security secretary—it was one of the reasons he chose her.

Nick Miroff: ‘Maybe DHS was a bad idea’

While Noem played to the cameras, Ainsley writes, Lewandowski was busy accumulating an “unchecked level of power” inside DHS. Officials were reluctant to question him out of fear that they’d be terminated by Noem, and a chill settled over any meetings that he attended. “She would ask, ‘Why is everyone so quiet?’ when it was plain to see people were afraid to speak up in front of Corey,” one of the CBP officials told Ainsley. “What are you going to do? Make an accusation? They’ll tear you apart,” the official said.

One policy that Lewandowski took a particular interest in, according to Undue Process, was migrant-detention centers. Inside the administration, Ainsley writes, a divide had formed over how to house the millions of immigrants Trump wanted to arrest. One group, which included “border czar” Tom Homan, favored scaling up the construction of traditional brick-and-mortar facilities. But Lewandowski was dead set on a cheaper, more austere solution: He envisioned shuttling detained migrants to tent cities in punishing locations. His lobbying ultimately led to the creation of the notorious “Alligator Alcatraz” facility in the Florida Everglades as well as a tent compound in Guantánamo Bay.

Lewandowski also took a heavy-handed approach to distributing DHS contracts, Ainsley writes, insisting that any expenditure over $100,000 be signed off by himself and Noem. Previously, a secretary’s sign-off was required only for expenditures of $25 million or more. The new policy prompted contractors to complain to the White House.

But even those within the administration who objected to his management of the department were reluctant to challenge him without a “smoking gun,” Ainsley reports. As one White House official put it, Lewandowski was like a cockroach who’d grown immune to insecticide—getting rid of him was easier said than done.

Thursday, February 26, 2026

Senate Majority Leader rejects Trump's call to eliminate filibuster to pass SAVE Act

Trump’s speech to Congress on Tuesday continues to roil the American political landscape. The lead story in the NYTimes reflects a widespread anxiety that Trump will interfere with the 2026 midterms—a fear exacerbated by the warm reception congressional Republicans gave to Trump’s lies about the SAVE Act. See NYTimes, Trump’s Push for Election Power Raises Fears He Will ‘Subvert’ Midterms | The president appears to be undermining Americans’ faith in the outcome, at a moment when Republicans face an uphill climb to keep control of Congress. (Accessible to all.) The Times’ editorial decision to feature a story about election integrity following Trump’s speech reflects the mood of the electorate. Indeed, the most frequent topic of reader emails over the last two months has been the threat to the midterms. Will they occur? Will Trump rig the result? Will he use the FBI to seize ballots? Will Congress pass the SAVE Act? If so, will it disproportionately disenfranchise Democratic voters? Will ICE show up at the polls to intimidate voters? We must remain vigilant against voter suppression and election interference—and we must support those on the front lines of that effort, such as Marc Elias’s firm and his voter protection publication, Democracy Docket. On Wednesday, two reports suggest that some of our worst fears may not materialize. We can take nothing for granted, but we must also avoid fear-fueled repetition of threats to the midterms that normalize the very threats we seek to prevent. In his Tuesday speech, Trump called on Congress to pass the SAVE Act. His call to action was met by a standing ovation from Republicans. But under Senate rules, Republicans need 60 votes to cut off debate and bring the SAVE Act to the floor for a vote. Although the SAVE Act could become law with 51 votes on the Senate floor, Republicans need 60 votes to end debate (“cloture”) to bring the bill to the floor, a procedural requirement known as the “filibuster.” There are only two ways for the SAVE Act to pass in the Senate: convince seven Democrats to support the SAVE Act, or create a carve-out to the filibuster. Only one Democrat (John Fetterman) has said he will vote in favor of the SAVE Act. Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski has said she will vote against the Act, meaning that Republicans still need seven Democrats to pass the Act. Recognizing that Republicans don’t have the votes to overcome the filibuster, Trump used his speech to urge Republicans to create a carve-out to the filibuster to pass the SAVE Act. For more than six months, Senate Majority Leader John Thune has said that he does not support modifying the filibuster to pass the SAVE Act. Moreover, Senator Mitch McConnell is preventing the bill from being advanced out of committee, a necessary prerequisite for a floor vote, where the filibuster would block its passage. McConnell warned that creating a carve-out to the filibuster would “lay[] the groundwork for a leftwing election takeover” if Democrats retake the White House and Congress.” Here’s the important point: After Trump’s speech, GOP Leader John Thune reiterated his opposition to modifying the filibuster to pass the SAVE Act. See Democracy Docket, Despite Trump’s SOTU and MAGA pressure, Sen. Maj. Leader Thune in no hurry to change filibuster, vote on SAVE America Act. Thune’s post-speech statement that he opposes modifying the filibuster to pass the SAVE Act is big news—and goes some distance to quelling fears that the Senate will pass the SAVE Act. But many readers have raised a proposal being promoted by Republican Senator Mike Lee to use a “talking filibuster” to cram the SAVE Act through the Senate. The use of a “talking filibuster” is just another way of saying that Republicans will create a carve-out to the filibuster, which John Thune and Mitch McConnell are blocking. The following details about the talking filibuster are “in the weeds,” but I have received enough emails from worried readers about this possibility that it warrants a mention in the newsletter. Skip this analysis if you want; it is just a specific case of carving out the filibuster. The standing rules of the Senate allow senators to exercise the filibuster (i.e., prevent cloture of debate) merely by indicating their intent to do so. Think of this as a “silent” filibuster. Senators invoking a silent filibuster are not required to “hold the floor” through marathon speeches as in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. In contrast, under the talking filibuster, when Democrats run out of steam, the “talking filibuster” would be over, and the bill could advance to a floor vote for passage by the Republican majority. How does Senator Lee propose to force a “talking filibuster? There are two paths to doing so. First, Senate rules could be amended to force a “talking filibuster” on the SAVE Act. But amending Senate rules for a talking filibuster would require 67 votes to make that change—more than the number of votes necessary to overcome the filibuster! See Senate Rule XXII and Congressional Research Service, Filibusters and Cloture in the Senate Second, Republicans could use the “nuclear option” to change Senate rules by altering the “precedent” governing the applicability of the talking filibuster to the SAVE Act. Creating a new precedent requires only 51 votes and would circumvent the silent filibuster, substituting the talking filibuster, which ends when Democrats collapse from exhaustion or lose their political will to grind the Senate to a halt. See Wikipedia, Nuclear option. In other words, forcing a “talking filibuster” (which will eventually end) is the same thing as creating a carve out to the filibuster—which John Thune and Mitch McConnell oppose. So, saying that Republicans will use the “talking filibuster” to pass the SAVE Act is the same as saying that they will abolish the filibuster to pass the SAVE Act. They might (anything is possible), but Republicans do not want to do so because the filibuster allows Republicans to maintain minority rule. If the GOP abolishes the filibuster, Democrats will pass the John Lewis Freedom to Vote Act at the first possible moment. That bill will spell the doom of the Republican Party. In the words of Mitch McConnell, abolishing the filibuster to pass the SAVE Act will “lay the groundwork for a leftwing election takeover” by allowing passage of the John Lewis Freedom to Vote Act, thereby eliminating partisan gerrymandering and restoring the preclearance requirement of the Voting Rights Act that the Supreme Court dismantled in Shelby County v. Holder. I do not mean to suggest that people should relent in their pressure campaigns on their elected representatives in Congress. But neither should Democrats suffer under exaggerated fears that Republicans will pass the SAVE Act through a “talking filibuster.” John Thune and Mitch McConnell are using control over the Senate calendar to ensure that Republicans leave the filibuster intact. Separately, a DHS official told state election officials that ICE agents will not be at the polls in 2026. See HuffPo, DHS Official Says ICE Won’t Be At The Polls. Per HuffPo,

Sounds good, right? Well, there is one very significant caveat. The person who gave the assurance is an election denier who backed Trump’s assault on the 2020 election and is now in charge of election security for 2026. We have reason to be skeptical of the DHS representative’s assurance. Still, it could have been otherwise. The DHS official could have evaded the question or given an equivocal answer. It is doubtful that anyone in the Trump administration would give such a forceful denial unless it represented the administration’s current policy. Trump could change that policy for no reason or for a silly reason, like eating a Big Mac gone bad. But, for now, the administration is saying that ICE will not be at the polls. As I said, it could be otherwise. Update on missing interviews of 13-year-old victim who alleges that Trump abused her.Earlier in the week, NPR and MSNow reported that the Epstein files produced by the DOJ were missing three interviews of a 13-year-old who accused Trump of sexually abusing her. The DOJ initially responded that any documents withheld fell within permitted exceptions to the Epstein Files Transparency Act. On Tuesday, the DOJ said the files might be related to an ongoing federal investigation. On Wednesday, the DOJ said it would produce documents mistakenly withheld. Per NPR,

The evolving position of the DOJ in response to the omissions suggests that they know they have a problem and they are looking for a way out. The issue of omitted FBI interview notes is gaining steam. Cries of “cover-up” are emerging. (“Rep. Garcia stated on the record, “There is definitely, in my opinion, evidence of a cover-up happening. Why are these documents missing?”) Those cries will only grow until the DOJ relents and releases the documents related to accusations against Trump. Such disclosure will not be the end of the inquiry; rather, it will be just the beginning. Cuba fires on boat with 10 people aboard; rescues survivors.Cuba claims that a boat with ten American residents who were allegedly attempting to infiltrate Cuba was destroyed by the Cuban Border Guard Troops. Four people were killed; the six survivors were “evacuated and received medical assistance,” per a government statement. See AP, Cuba says boat from Florida opened fire at its soldiers, starting fight that killed 4. The difference in treatment of survivors at sea by the Cuban government and the US government is striking. Cuba offered the survivors medical assistance (although they are being detained), while the US unleashed two Reaper Drones at two men clinging to a shipwreck. Trump’s surgeon general nominee is evasive about stance on vaccines.Here we go again. Trump has nominated Casey Means to be US Surgeon General. Although Means graduated from Stanford Medical School, she did not finish her residency and is not a licensed physician. Her most relevant qualification appears to be that she is the “sister of White House senior adviser Calley Means, one of Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s top advisers, and a prominent “Make America Healthy Again” influencer in her own right.” See The Hill, Trump’s atypical surgeon general pick faces Senate scrutiny: Key takeaways As to her stance on vaccines, in response to a question by Republican Senator Bill Cassidy, she “declined to say if she’d encourage other mothers to get their children vaccinated against measles.” No Democratic Senators should support Means, and the handful of Republicans who opposed Robert Kennedy should vote against Means. Last time around, Senator Cassidy was the deciding vote. Let’s hope he has learned his lesson. Concluding ThoughtsWhen I describe Trump’s declining favorability ratings, readers often respond, “Yes, but the Democratic Party’s ratings are abysmal, as well.” That is a classic case of a category error—comparing two things that are fundamentally different. Trump is a person with political positions and a known set of accomplishments and failures. In contrast, the “Democratic Party” is a collection of people with a wide range of viewpoints, experiences, and accomplishments. A better measure of the effect of Trump’s unfavorability ratings is the elections held over the last year between Trump acolytes and Democratic candidates. When voters compare two things in the same category—specific candidates—Democrats have been consistently winning by double digits. So, the generalized “abysmal ratings” of the Democratic Party writ large are not controlling in a contest between two flesh-and-blood candidates. Using Trump as a surrogate for dozens of Republican candidates in specific elections is logical because almost all Republicans defend Trump’s agenda and corruption without exception. Democrats, on the other hand, bring a variety of viewpoints to the table. There is a second way in which the alleged “abysmal ratings” for Democrats is not supported by the facts on the ground. A Washington Post-ABC poll revealed that Democratic voters are much more “enthusiastic” about voting in 2026. See WaPo, Republicans stare down epic voter enthusiasm gap ahead of 2026 midterms. Per WaPo,

The general finding in the WaPo/ABC poll is manifesting itself in the current Texas primaries, where voting is taking place as I write. See Mediaite, CNN’s Harry Enten Floored Dems Are Out-Voting GOP In Texas. Per Mediaite,

Of course, voting patterns can shift over the course of long voting windows, but as of now, the “enthusiasm” among Texas Democrats appears to be substantially higher than that of Texas Republicans. None of the above should cause you to relent in your efforts. But neither should we make the “category error” of comparing a generalized rating for the Democratic Party with enthusiasm for specific Democratic candidates running against Trump clones. We should not engage in self-delusion by telling “just so” stories, but neither should we increase our anxiety by comparing the popularity of “Granny Smith apples” to “fruit.” Talk to you tomorrow! |

LINKS TO RELATED SITES

- My Personal Website

- HAT Speaker Website

- My INC. Blog Posts

- My THREADS profile

- My Wikipedia Page

- My LinkedIn Page

- My Facebook Page

- My X/Twitter Page

- My Instagram Page

- My ABOUT.ME page

- G2T3V, LLC Site

- G2T3V page on LinkedIn

- G2T3V, LLC Facebook Page

- My Channel on YOUTUBE

- My Videos on VIMEO

- My Boards on Pinterest

- My Site on Mastodon

- My Site on Substack

- My Site on Post

LINKS TO RELATED BUSINESSES

- 1871 - Where Digital Startups Get Their Start

- AskWhai

- Baloonr

- BCV Social

- ConceptDrop (Now Nexus AI)

- Cubii

- Dumbstruck

- Gather Voices

- Genivity

- Georama (now QualSights)

- GetSet

- HighTower Advisors

- Holberg Financial

- Indiegogo

- Keeeb

- Kitchfix

- KnowledgeHound

- Landscape Hub

- Lisa App

- Magic Cube

- MagicTags/THYNG

- Mile Auto

- Packback Books

- Peanut Butter

- Philo Broadcasting

- Popular Pays

- Selfie

- SnapSheet

- SomruS

- SPOTHERO

- SquareOffs

- Tempesta Media

- THYNG

- Tock

- Upshow

- Vehcon

- Xaptum

Total Pageviews

GOOGLE ANALYTICS

Blog Archive

-

▼

2026

(398)

-

▼

February

(213)

- CLOWNS, MORONS AND FOOLS IN THE CABINET

- SECRETARY CLINTON'S OPENING STATEMENT TO THE HOUSE...

- IT'S ALWAYS ABOUT EPSTEIN

- Trump’s Attack on Iran Is Reckless

- The SOTU speech was a sad joke

- CBS IS TOAST - VERY SAD

- The First Couple of a Dysfunctional DHS

- Senate Majority Leader rejects Trump's call to eli...

- EdTech is Borrowing Zuckerberg's Playbook

- CRAZY AND CORRUPT ON DISPLAY

- A Republican’s Sex Scandal Could Paralyze the House

- John Roberts Is Losing Patience With Trump

- SE Cupp

- Heather - 2-24

- Heather 2-23

- CBS is unraveling — and it goes beyond Bari Weiss

- Justice Department withheld and removed some Epste...

- FASCIST FAILURE

- GRAND JURY

- The Truth

- TONY G TOPS A LONG LIST OF MAGATS WHO ARE PERVERTS...

- ANOTHER CRUSHING LOSS FOR TRUMP AND PIRRO WHO IS A...

- NEW INC. MAGAZINE COLUMN BY HOWARD TULLMAN

- Hey Team USA Men's Hockey, Congratulations, You Ju...

- TONY'S GOTTA GO NOW..

- DEMENTED DON

- Don’t let the media tell you this dumpster fire is...

- SAYS IT ALL...

- BIG QUESTION FOR TOMORROW NIGHT

- Trump Got Boycotted By Governors, Smacked Down In ...

- JOYCE VANCE

- EPSTEIN UPDATE

- The Decaying Legal Culture in the Defense Department

- Days after $5M donation, Trump administration back...

- Boycott the State of the Union

- Let’s take the win on tariffs.

- Kash Patel Takes a Victory Lap

- You Do Not, Under Any Circumstances, Gotta Hand It...

- STOP THE SAVE ACT

- Heaven and Hell in American Politics

- It's SOTU Time!

- Does Trump really think he can get away with this?

- The State Of The Union Is That We've All Had Enoug...

- ASHA

- Talking With Ro Khanna

- TRUMP BUTT KISSER STRIKES AGAIN

- DOWD

- HUBBELL

- FRUM

- HEATHER

- RAND PAUL

- FUCK FOX

- ROBERT HUBBELL

- HEATHER

- PAUL KRUGMAN

- BONDI BONANZA

- BORED OF SLEEP

- When White Racial Rescue Becomes a Foreign Policy ...

- NUTLICK

- He Studied Cognitive Science at Stanford. Then He ...

- HEATHER

- Please, oh please(!), send Cabinet secretaries to ...

- Stephen Colbert and the First Amendment

- QUIET PEDO

- EPSTEIN FOREVER

- Has Mass Deportation Become A Domestic Vietnam For...

- Taking Stock of the Roberts Court at 20—and the Sh...

- ROBERT HUBBELL

- TRUMP

- Epstein uber alles

- The DHS Death Spiral

- Bondi is Trump's Maxwell - Groomed by Perverts and...

- HEATHER

- THESE COMMENTS BY LYLE FASS CAME IMMEDIATELY TO MI...

- NEW INC. MAGAZINE COLUMN FROM HOWARD TULLMAN

- DAN RATHER

- THE WORST PRESIDENT IN HISTORY

- Is Artificial Intelligence the Next Great Bubble?

- The Epstein Files: The Blackmail of Billionaire Le...

- LET'S BE CLEAR - VANCE IS A CLASSLESS LYING PIG WH...

- Brace Yourself for the AI Tsunami 15.02.202622:0...

- The Bill Has Come Due

- Trump On President's Day - Rot, Failure, And Decline

- RFK JR IS CERTIFIABLE

- NOT ENOUGH

- Epstein ran the biggest sex ring ever and now Pam ...

- Marco Rubio's Munich Security Conference Speech

- The Squalor of the Epstein Class

- Insult everyone. Answer for nothing.

- The Worst President Ever

- How technology has already changed the world in my...

- Something Big Is Happening

- What Being a Billionaire Scion Taught JB Pritzker ...

- SAVE ACT IS ANOTHER MAGAt SCAM

- Pedo Protectors

- The Trump Administration Is Developing a Multi-Pro...

- A Dose of Hard Truths

- Welcome to the Voyage of the Damned

- A Fight Democrats Must Win

- HEATHER

-

▼

February

(213)