Breaking the Fourth Amendment

Last night, we learned from a report in the Associated Press that ICE, contrary to longstanding Fourth Amendment jurisprudence, is taking the position that it can enter people’s homes without a judicial warrant. Instead, they believe that an administrative warrant suffices. An administrative warrant is a form signed by an “authorized immigration official,” which means an executive branch employee who can be fired if they displease the president. It’s not difficult to see the problem here.

The Fourth Amendment provides that: “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.” It’s the reason your home can’t be searched by the police without a search warrant that has been supported with probable cause to believe that evidence or fruits of a crime will be found there.

ICE seems to be arguing that if they think a non-citizen for whom there is a final order of deportation is in a house, they can blow right past the Fourth Amendment, take the doors off the house if they aren’t admitted voluntarily, and go right in. But the Fourth Amendment doesn’t change just because ICE says so.

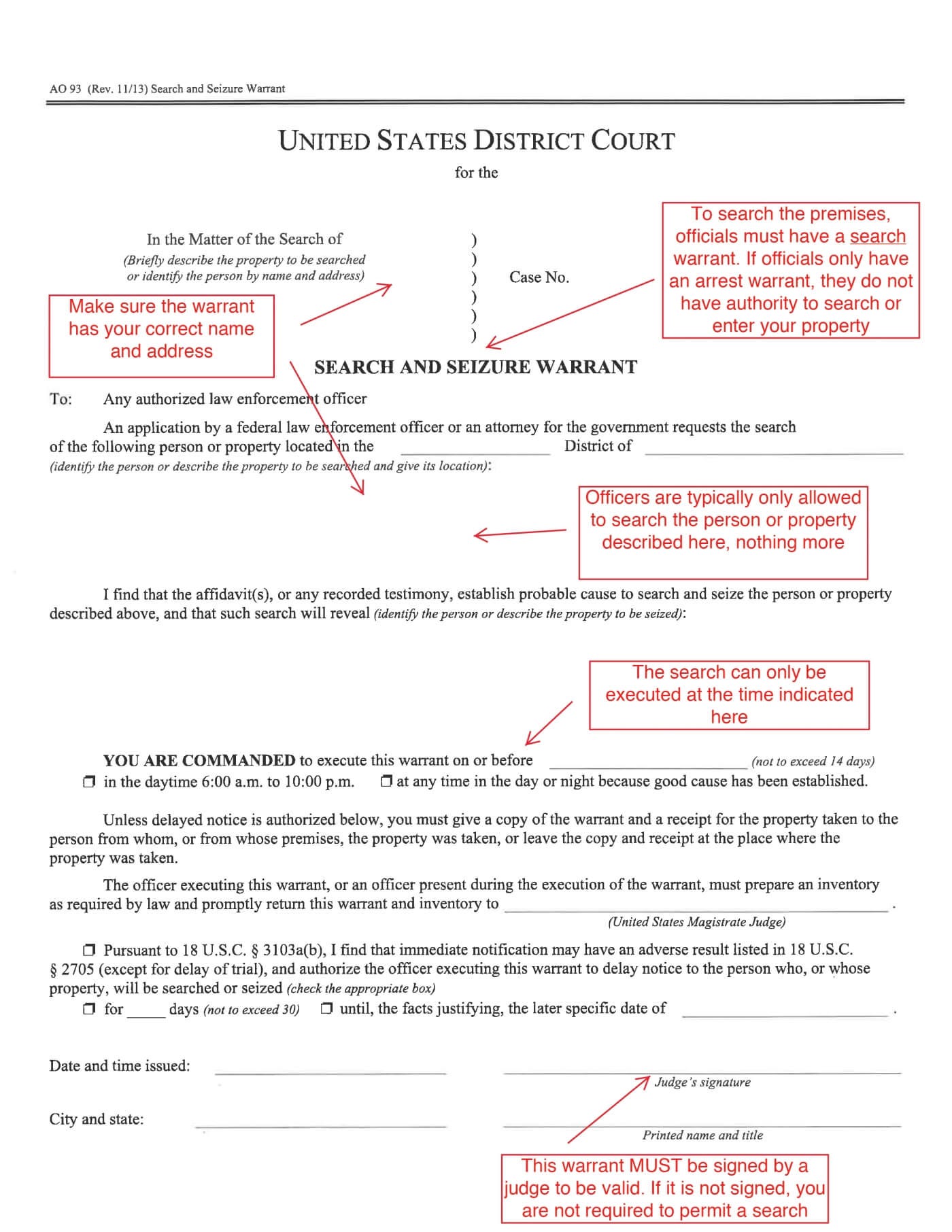

The Supreme Court has made it clear that a search warrant must be signed by a “judicial officer” or a “magistrate.” Their signature on the warrant says that they have reviewed the evidence that the agents believe constitutes probable cause to justify a search, and they agree that it is sufficient to breach the wall otherwise established by the Fourth Amendment and allow law enforcement into a private home (or car, or private areas of a business, etc.). The idea is that a detached, neutral judge—not someone involved in investigating a case or “on the same side” as law enforcement—should evaluate the evidence before a search warrant or an arrest warrant is issued.

As the Supreme Court explained in Johnson v. U.S., in 1948: “The point of the Fourth Amendment, which often is not grasped by zealous officers, is not that it denies law enforcement the support of the usual inferences which reasonable men draw from evidence. Its protection consists in requiring that those inferences be drawn by a neutral and detached magistrate instead of being judged by the officer engaged in the often competitive enterprise of ferreting out crime.”

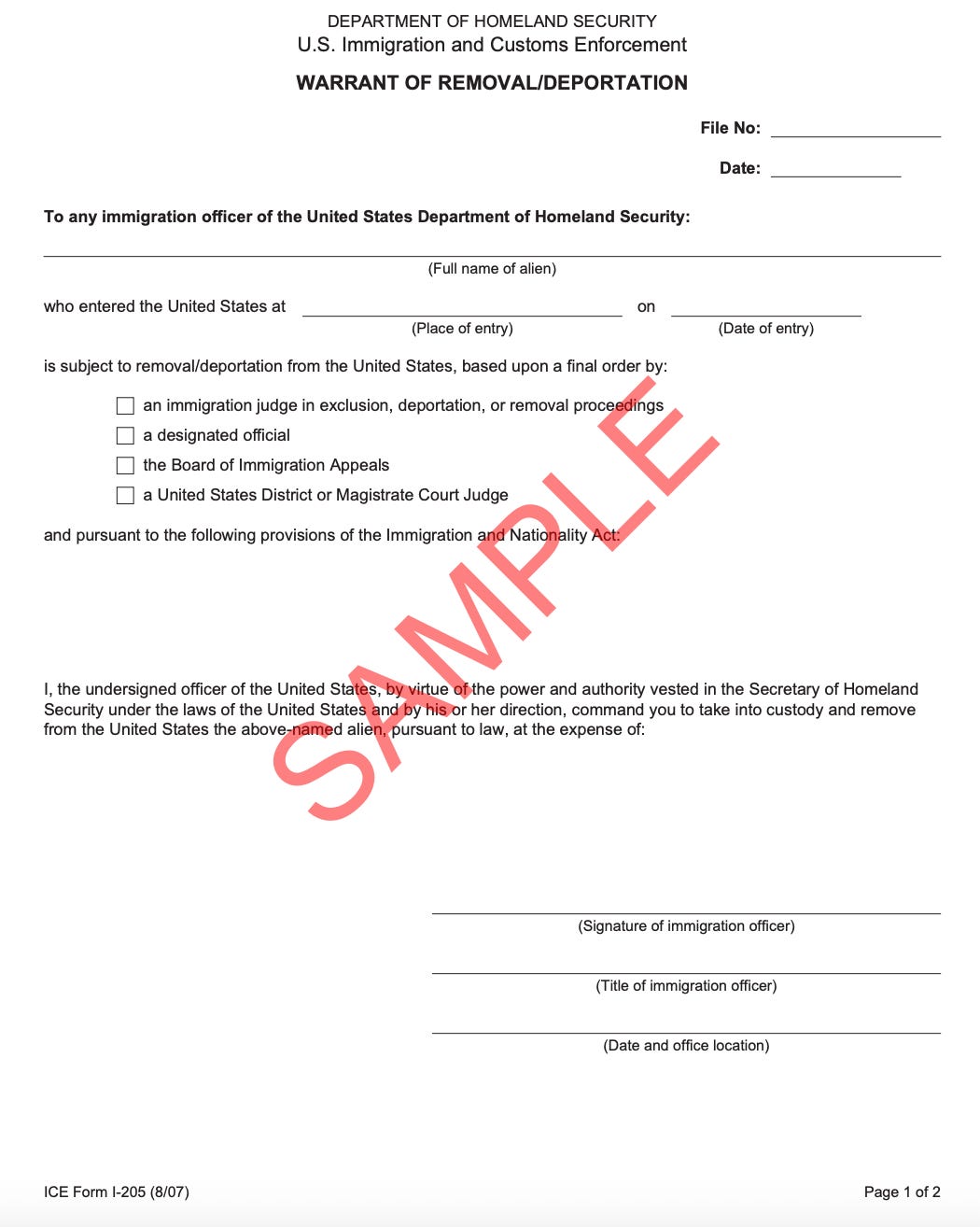

The Fourth Amendment means that if law enforcement comes to your door and says they want to search, the first thing to do is to ask to see the warrant. ICE’s new policy adds a wrinkle to this. Now, to make sure their rights are protected, people will have to determine whether the warrant is a lawful judicial warrant, in which case they must allow officers to enter, as long as the warrant is for the correct location, or whether it’s an administrative warrant, in which case they can deny entry.

This is an example of a judicial warrant, annotated by lawyers at the ACLU who use it as an example for training. You can see that it’s a district court form, and at the bottom, the signature block is for a judge. The warrant is only valid if it’s signed by a judge.

Compare that to an administrative warrant, which is not sufficient for Fourth Amendment purposes. Note that it requires the signature of an “immigration officer,” an executive branch employee. That runs afoul of the Court’s requirement of a neutral and detached magistrate. This warrant might permit agents to arrest the person who has a final deportation order if they are found in a public place. It doesn’t permit the search of a home.

But ICE’s new policy raises the concern that agents will go right on in, relying on the new policy. The whistleblower complaint that made it public alleges that the memo, signed by Acting ICE Director Todd Lyons, states, "Although the U.S. Department of Homeland Security has not historically relied on administrative warrants alone to arrest aliens subject to final orders of removal in their place of residence, the DHS Office of General Counsel has recently determined that the U.S. Constitution, the Immigration and Nationality Act, and the immigration regulations do not prohibit relying on administrative warrants for this purpose.”

DHS Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs Tricia McLaughlin unintentionally confirmed the illegality of the use of a DHS form I-205 as though it were a judicial search warrant. She said, "Every illegal alien who DHS serves administrative warrants/I-205s have had full due process and a final order of removal from an immigration judge. The officers issuing these administrative warrants also have found probable cause. For decades, the Supreme Court and Congress have recognized the propriety of administrative warrants in cases of immigration enforcement." Yes, administrative warrants may suffice for deportation. But they don’t make the Fourth Amendment irrelevant. ICE seems to be conceding that is the position that it’s now taking.

In a week where we’ve seen a protester held on the ground while chemicals are sprayed in their face and a five year old boy used as bait to lure his father before putting the child in deportation proceeding on his own—two stories that shock the conscience and conjure up black and white pictures of the Gestapo, violating the Fourth Amendment might seem like something that should take a backseat. But it’s equally important. The Whistleblower complaint says that the ICE policy authorizes agents to use “a necessary and reasonable amount of force to enter the alien's residence." Even without a lawful warrant, ICE may be instructing its agents to force their way into people’s homes illegally.

ICE knew the advice it was giving wouldn’t pass muster. Policies that provide operational guidance to agents are written, emailed throughout an agency, and often available publicly. That didn’t happen here. The whistleblower said it was “tightly held” at DHS. “The May 12 Memo has been provided to select DHS officials who are then directed to verbally brief the new policy for action,” the complaint states. “Those supervisors then show the Memo to some employees, like our clients, and direct them to read the Memo and return it to the supervisor.” Training on the memo was done verbally, but the policy was not provided in writing.

Nothing says agency leaders know they’re violating the law like that kind of unusual treatment.

Senator Richard Blumenthal said, “It is a legally and morally abhorrent policy that exemplifies the kinds of dangerous, disgraceful abuses America is seeing in real time. In our democracy, with vanishingly rare exceptions, the government is barred from breaking into your home without a judge giving a green light.”

Sunlight is a good disinfectant for government abuse. The hope here is that by exposing the policy, ICE will be deterred from using it in the future. It’s an outrageous abuse, as they seem well aware. But there are stories, including the two we discussed last night, that suggest there may be civil lawsuits against the agency in the offing and perhaps a more proactive attempt to get the courts to prohibit this practice. None of that would be necessary with an administration that was acting in good faith. But it’s abundantly clear that this one isn’t.

Evil triumphs when good people do nothing. That’s why it's important that we contact our elected officials in Congress and demand that they investigate and demand that ICE retract its policy. We know that this administration continues to push the limits once it gets started. At first, it may have been noncitizens with deportation orders. Some people may have thought it was okay, lawful, but awful. This week, it was a frail, elderly American citizen, forced out into the icy cold and detained after ICE entered his home without a judicial warrant. There is no telling where this will end up if we don’t shine a spotlight so bright that ICE can’t withstand it.

Thanks for being here with me at Civil Discourse. Your paid subscriptions make the newsletter possible, and your interest in learning and being engaged citizens makes it worthwhile.

We’re in this together,

Joyce