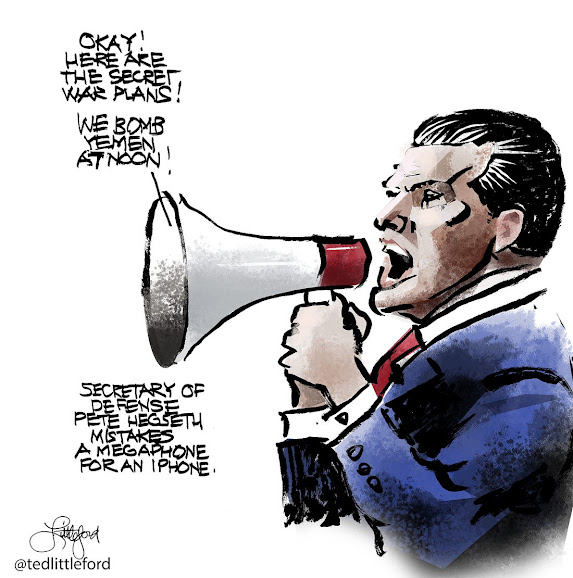

Hegseth Signal messages came from email classified

‘SECRET,’ watchdog told

The

revelation contradicts the Trump administration’s longstanding claims that no

classified information was shared by the defense secretary’s account during the

“Signalgate” scandal.

July 23, 2025 at 3:51

p.m. EDTtoday at 3:51 p.m. EDT

By Dan Lamothe

and

The Pentagon’s independent watchdog has received evidence

that messages from Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s Signal account previewing a

U.S. bombing campaign in Yemen derived from a classified email labeled

“SECRET/NOFORN,” people familiar with the matter said.

The revelation appears to contradict long-standing claims

by the Trump administration that no classified information was divulged in

unclassified group chats that critics have called a significant security

breach.

The messages about the bombing campaign, posted in at least

two group chats using the unclassified messaging app Signal, are the focus of

an inquiry by the Defense Department inspector general’s office requested in

April by Republican and Democratic members of the Senate Armed Services

Committee.

The strike plans had been shared in a classified email with

more than a dozen defense officials by Gen. Michael “Erik” Kurilla, the top

commander overseeing U.S. military operations in the Middle East, and then were

posted in the unclassified group chats by an account affiliated with Hegseth on

March 15, shortly before the United States began attacking Houthi militants,

the people familiar with the matter said.

The “SECRET” classification of Kurilla’s email, which has

not previously been reported, denoted that the information was classified at a

level at which unauthorized disclosure could be expected to cause serious

damage to national security. The “NOFORN” label means it also was not meant for

anyone who is a foreign national, including senior officials of close allies of

the United States.

In accordance with government regulations, Kurilla sent his

sensitive message over a classified system, the Secret Internet Protocol Router

Network, or SIPRNet, four people familiar with the matter said, speaking on the

condition of anonymity to avoid reprisal by the Trump administration.

The message included a rundown of strike plans for the day,

including when bombing was expected to begin and what kind of aircraft and

weapons were to be used. The disclosure of the sensitive information drew both

criticism and bewilderment because the group chat inadvertently included a

journalist from the Atlantic magazine who is a frequent critic of President

Donald Trump.

The scandal has caused numerous Democrats and

at least one Republican to

call for Hegseth’s firing, and dogged the defense secretary through a series of

congressional hearings in June. Senior administration officials have repeatedly

insisted that no classified information was shared on Signal, though national

security experts and former top military officials have said that is highly doubtful.

Administration officials doubled down on those claims in

new statements to The Washington Post, touting its actions in the military

campaign against the Houthis in Yemen earlier this year and more recently in

strikes against Iranian nuclear facilities.

“The Department stands behind its previous statements: no

classified information was shared via Signal,” said Sean Parnell, a Pentagon

spokesman, in an emailed statement. “As we’ve said repeatedly, nobody was

texting war plans and the success of the Department’s recent operations — from

Operation Rough Rider to Operation Midnight Hammer — are proof that our

operational security and discipline are top notch.”

Anna Kelly, a White House spokeswoman, pointed out that the

Houthis, a militant group long affiliated with Iran, have since agreed to a

ceasefire and criticized The Post for continuing to scrutinize what happened in

the Signal affair, even as the Defense Department inspector general continues

to do the same at the request of lawmakers.

“This Administration has proven that it can carry out

missions with precision and certainty, as evidenced by the successful

operations that obliterated Iran’s nuclear facilities and killed terrorists,”

Kelly said in a statement.

Kelly added: “It’s shameful that the Washington

Post continues to publish unverified articles based on alleged emails they

haven’t personally reviewed in an effort to undermine a successful military

operation and resurrect a non-issue that no one has cared about for months.”

In seeking comment from the White House, The Post disclosed

that four people familiar with Kurilla’s email verified its SECRET/NOFORN

classification.

\

The apparent creator of the main Signal group at issue,

former White House national security adviser Michael Waltz, was ousted from his job less

than two months after the episode was revealed in March. Numerous top

administration officials were also part of the group chat, including Vice

President JD Vance, Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Director of National

Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard.

Waltz, now Trump’s nominee to be U.S. ambassador to the

United Nations, came under criticism last week during his confirmation hearing

for refusing to concede the unclassified group chat was a mistake.

“I was hoping to hear from you that you had some sense of

regret over sharing what was very sensitive, timely information about a

military strike on a commercially available app,” said Sen. Chris Coons

(D-Delaware). “We both know Signal is not an appropriate and secure means of

communicating highly sensitive information.”

Waltz, who like Hegseth served as an Army officer before

entering politics, also insisted that “no classified information was shared.”

He did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

At a House Armed Services Committee hearing in June,

Hegseth, under questioning by Rep. Seth Moulton (D-Massachusetts), refused to say whether

the Yemen strike details later shared on Signal initially came to his office

over a classified system. The open event was not an appropriate venue to

address such questions, Hegseth argued.

“Classifications of any information in an ongoing operation

that was successful are not things that would be disclosed in a public forum,”

he said.

Moulton, a Marine Corps veteran, disputed that. “It’s not

classified to disclose whether or not it was classified,” the congressman said.

“And in fact, DoD regulations state that any classified information has to be

labeled with its classification.”

Moulton pressed Hegseth on whether he was trying to assert

that the information he received from Kurilla’s headquarters was unclassified.

Hegseth dodged.

“I’m not trying to say anything,” Hegseth responded.

The Defense Department inspector general’s office declined

to comment and has a general policy of not commenting on open cases.

Its review, whose findings are expected to be released

within a few months, poses another threat to Hegseth, whose six-month tenure as

defense secretary has been marked by infighting and dysfunction, including the

firing of numerous senior military officials and political appointees on

Hegseth’s own team and abrupt voluntary departures by

others.

Government regulations allow for the defense secretary to

declassify and downgrade classified information produced by the Pentagon, but

the Trump administration has yet to claim that such a process was carried out

before the sensitive information was shared over Signal. Two people familiar

with the evidence the inspector general’s office is reviewing said they were

aware of no such discussion having occurred before the scandal erupted.

NBC News reported in April about

the transfer of information from Kurilla’s message to the Signal chats, while

the Wall Street Journal reported in May that

the inspector general was scrutinizing one group chat that included Cabinet

officials and another that included Hegseth’s wife, Jennifer; his brother,

Phil; and his personal attorney Tim Parlatore. Jennifer Hegseth has no official role in the Pentagon,

while Phil Hegseth has worked as a liaison on matters pertaining to the

Department of Homeland Security, and Parlatore serves as a part-time military

aide in addition to being Hegseth’s personal lawyer.

Part of the emphasis of the inspector general’s review will

be to establish who posted messages that may have been classified in the group

chat under Hegseth’s name, people familiar with the matter said. In addition to

the defense secretary, Marine Corps Col. Ricky Buria,

then a military aide to Hegseth, had access to his personal phone and sometimes

posted information on his behalf, officials familiar with the matter said.

Individuals interviewed by the inspector general said Buria told colleagues

that he typed the controversial Yemen texts into Hegseth’s phone, people

familiar with the matter said. Buria has not spoken publicly about the matter

and did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Such information, before an operation, would generally

always be classified to protect the U.S. troops involved, security experts have said.

Retired Adm. William McRaven, the Navy SEAL officer who oversaw the raid that

killed al-Qaeda mastermind Osama bin Laden, said in April that

Hegseth’s team has not handled the controversy well and “clearly, the

information broadcast on Signal was classified.”

U.S. troops at all ranks are instructed on how to handle

classified information, and some have faced disciplinary action on numerous

occasions for not doing so correctly, sometimes at courts-martial.

Buria abruptly submitted retirement paperwork in April and

has since become a de facto chief of staff to Hegseth, a political position. He

frequently appears at the defense secretary’s side. Trump and Hegseth

recently authorized Buria to retire from the

Marines as a colonel, bypassing federal law stating that, in most

cases, a military officer of his standing must serve three years at a rank to

retire with it.

Exceptions can be granted with a waiver, the law states, in

cases “involving extreme hardship or exceptional or unusual circumstances.”

People familiar with the issue said such waivers are rare and typically

reserved for difficult situations, such as a service member needing treatment

for cancer or another serious illness.