This past weekend has been an incredibly dark one.

I went to bed Friday night with the shooting at Brown University pressed against me like a second skin. Another school shooting. Yet another goddamn school shooting. Another campus, another place where students should’ve been thinking about papers or finals or nothing at all, and instead were running, hiding, waiting for instructions no one should ever need. What scares me most isn’t only that it happened — it’s that another school shooting has become a sentence we all understand instantly now, without explanation, without pause.

Snow was forecasted for New Jersey overnight. Two to four inches, they said. When I went to bed, it was barely coming down, just a thin flurry, undecided, the kind that doesn’t promise anything yet. I didn’t know if it would amount to much by morning. I only knew the weight in my chest had nowhere else to go, and sleep came the way it does when you finally stop trying to outrun what you’re carrying.

By the time I woke, the world had changed quietly. Nearly ten inches of snow had fallen while I lay still. Every branch was heavy with white, bowed under it. Bushes softened into shapes they didn’t have the night before. Sound itself seemed padded, the morning blanketed and hushed. It took my breath away.

While that snow was settling here — soundless, grain by grain, rewriting the landscape in white — the world elsewhere was anything but still.

On Sunday, on a beach in Australia, people had gathered for Hanukkah. For light. For ritual. For the simple human faith that public joy is still allowed. They came with children and elders, food and folding chairs, assuming safety the way most of us do — without thinking about it. And then gunfire tore through that assumption.

People dropped before they could process what was happening. Parents moved without thinking, folding themselves over children, bodies answering fear faster than thought ever could. Strangers clutched one another in the sand, counting shots, doing the math no one should ever have to do. Time narrowed. Breath became deliberate. Children cried until someone made them stop — not with comfort, but with urgency.

I can’t make sense of how those two things can exist at the same time — the quiet outside my window and the terror on that beach. How snow can soften the world here while it’s being torn open somewhere else. How beauty can keep happening alongside brutality, indifferent to us, asking nothing, offering no mercy. The planet keeps spinning, keeps making room for both, while our bodies struggle to hold the contradiction without breaking.

What happened in Australia is horrific. And it is also the exception. Since they changed their gun laws, mass shootings there have been extraordinarily rare. Rare enough that when one happens, it shatters something instead of dissolving into routine. Parents aren’t trained for it. Children aren’t drilled for it.

One of the people killed was a man who survived the Holocaust as a child. He escaped genocide, carried that history in his body for decades, built a life anyway, only to be murdered eighty years later in another act of hate. I don’t know how to hold that without breaking. Survival, it turns out, isn’t protection in a world that keeps choosing violence.

Thirteen years ago yesterday, at Sandy Hook, six- and seven-year-olds were murdered in their classrooms. Parents were called in to identify their children by their shoes.

Since then, nothing has changed when it comes to gun violence — except for the lives that were destroyed that dark day, and the countless others shattered in its wake. These shootings are still shocking. They still knock the breath out of you — if you refuse to become numb the way some people want us to. What has changed is the expectation that we should absorb it quietly, accept it as background noise, and move on.

None of this is inevitable. It keeps happening because it’s been decided — quietly, deliberately — that the rest of us will carry the fear while others carry on untouched.

Charlie Kirk — someone I vehemently disagreed with on everything — once said out loud that a certain number of gun deaths are simply the “price of freedom.” He wasn’t talking about himself. He was talking about other people. People whose lives were expendable to him. I remember how it landed when I heard it — the chill of it, the ease, the way it demanded nothing of him at all.

It wasn’t an argument. It was a calculation. A sentence that only works if the bodies belong to other people.

And every time I see Erika Kirk on television — asked to speak about grief, about healing, about retribution — I can’t help but notice what isn’t being asked. No one presses on that sentence. No one asks whose life was an acceptable exchange for freedom. Whose child. Whose daughter. Whose son. Whose mother. Whose teacher. Whose neighbor. Whose husband. The question hangs there anyway, unanswered.

This is a rot that starts at the top — because yesterday, just two days after the shooting at Brown University, Donald Trump said that “things can happen.”

The sheer audacity of it. The way he said it — casual, unbothered, conversational, an afterthought. As if he weren’t talking about a family suddenly standing in the wreckage of a before and an after they didn’t choose. As if a life ending were no more consequential than a missed connection or a flat tire. Language so small it tried to erase the devastation it was pointing at.

Years ago, when my daughter was in third grade, I was across town at another elementary school, on the floor, doing something ordinary. Helping a child color. Or finish a puzzle. I don’t remember which, because it doesn’t matter. What matters is that it was a morning like any other. I was at work. My daughter was at school. I didn’t have to think about whether she was safe.

Then the principal arrived and asked us to step into the hallway — myself and a colleague whose son was in my daughter’s class.

The first thing she said was not to worry — a sentence that collapsed almost immediately under the weight of what came next. My daughter’s school was on lockdown. An active shooter response. Police already there.

Everything inside me dropped out at once.

Later, we learned it was a mistake. But inside her classroom, no one knew that. Teachers pushed chairs against doors. One child cried and couldn’t stop. Another whispered that the crying was going to get them all killed.

My daughter was eight.

That moment never gave itself back. It came with us. It’s why her backpack is bulletproof now — why she chose it, not because it’s cute or trendy, but because she already understands something no child should have to understand about school in this country.

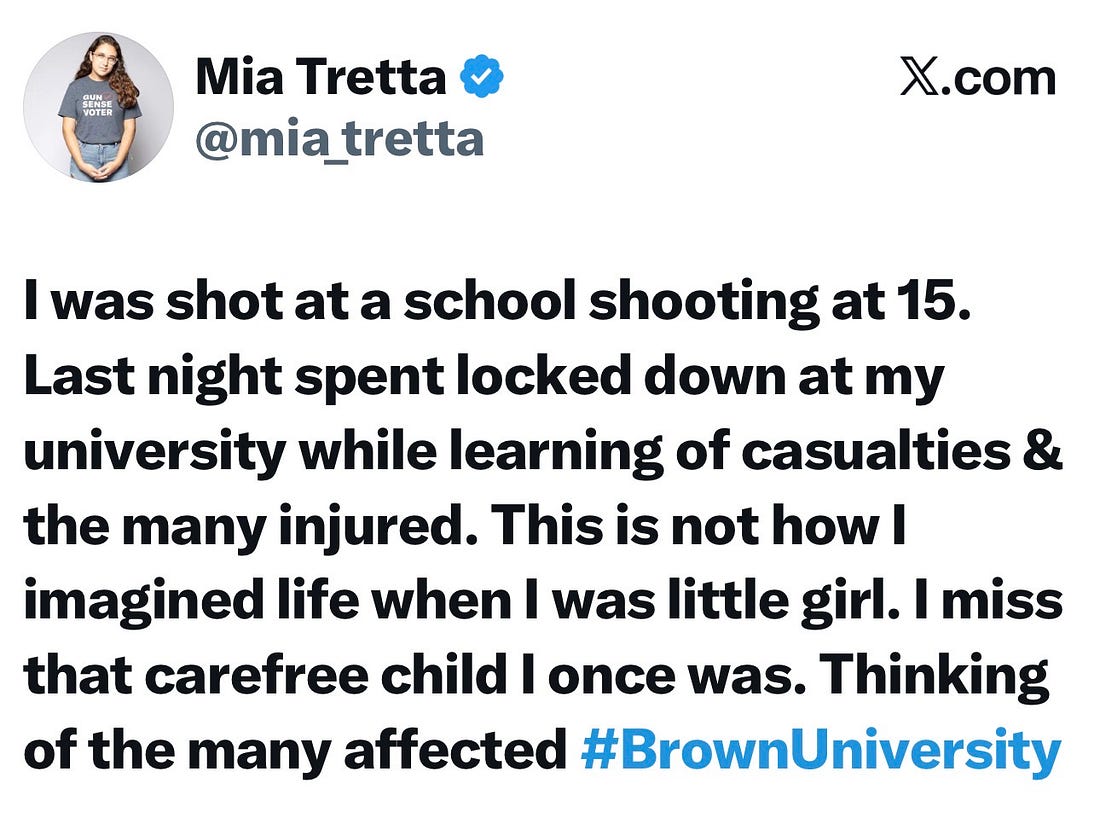

On Saturday, I read a post from my friend Mia Tretta. Mia survived a school shooting at fifteen. A bullet tore through her body. She watched her best friend die. She learned far too young what it feels like when safety disappears all at once. She goes to Brown now, carrying that history with her. The day after the shooting, she posted about it. She wrote, “I miss the carefree child I once was.”

That sentence stayed with me. Because that’s what keeps being taken. Innocence. Childhood. The unguarded years kids are supposed to get before the world teaches them to brace. We are raising children who learn too early how to scan rooms, how to find exits, how to live with fear folded quietly into their bodies.

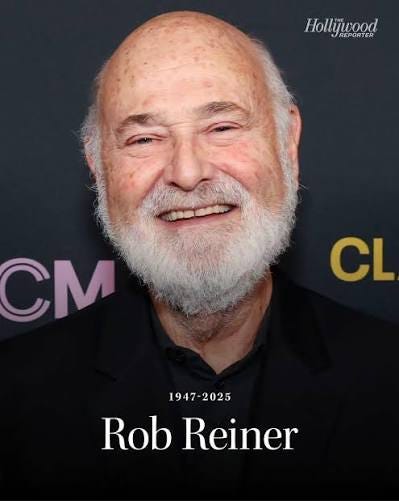

And just when I finally sat down to write — to try to put words to how all of this was landing — the news came in that Rob Reiner and his wife had been murdered in their home. I stopped mid-sentence, thumbs hovering over my phone, the letters suddenly gone. It was like the ground giving way again. Sadness layered on top of sadness on top of sadness. Every time I tried to stand up under it, something else came along and knocked me back down.

It’s Monday morning now, and I keep catching myself right on the edge of tears. That familiar pressure in the back of my throat. In my face. In my eyes. The kind that never quite breaks, just stays there, reminding you how much you’re holding. I know I’m not the only one feeling that way.

What makes it bearable is knowing I’m not carrying it alone. This community doesn’t ask anyone to be okay or articulate or brave. It just surrounds. It lets people show up tender and exhausted and overwhelmed, without needing to explain themselves. That quiet holding matters more than fixing anything ever could.

I’m grateful for you. For the way you see one another. For the way you let people feel what they feel without rushing them through it. If you’re reading this with that same tightness in your throat, that same welling behind your eyes, please know this: you are seen here. You are held here. And you are loved.