CBS is unraveling — and it goes beyond Bari Weiss

Wednesday, February 25, 2026

CBS is unraveling — and it goes beyond Bari Weiss

Anderson Cooper departs and Stephen Colbert goes off-script as the network struggles to define its future

In the span of months, one of America’s most storied broadcast institutions has managed to alienate its most recognizable late-night host and lose one of its most respected journalists, all while inviting scrutiny over whether it is voluntarily bending the knee to political pressure from the Trump administration. The optics are catastrophic.

CBS looks to have made a strategic blunder when it announced plans last year to cancel “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert” but decided to keep host Stephen Colbert on air until May 2026. The decision created a lame-duck host with a nightly platform and a growing sense of grievance. On Monday, Colbert told his studio audience that CBS lawyers had called his show “in no uncertain terms” to block an interview with Texas Democratic Senate candidate James Talarico. According to Colbert, the network didn’t just want to censor the content — it wanted to censor the censorship itself, informing him that he couldn’t even mention that he’d been prohibited from airing it.

“Because my network clearly doesn’t want us to talk about this,” he told his audience, “let’s talk about this.” He ultimately posted the interview to YouTube, where it has since drawn more than 5.2 million views — far more than it ever would have attracted as a routine late-night segment. (CBS said it had “not prohibited” Talarico’s interview from running but admitted it had “provided legal guidance” and given Colbert’s team “options for how the equal time for other candidates could be fulfilled.”)

CBS handed the shovel to the very man they were trying to bury, and he dug himself out. Colbert knows he has nothing to lose now.

It’s amazing how long we’ve known about the Streisand effect, the phenomenon where an attempt to censor or suppress information ends up drawing more attention to it, yet institutions still can’t resist stepping on the rake. CBS handed the shovel to the very man they were trying to bury, and he dug himself out. Colbert knows he has nothing to lose now. It’s worth noting that his public criticism of CBS parent company Paramount Skydance’s $16 million to settle Donald Trump’s lawsuit over a 2024 “60 Minutes” interview with Kamala Harris — a lawsuit that legal scholars widely regarded as meritless — is widely believed to be the real reason CBS canceled “The Late Show.”

The pretext CBS used to object to Colbert’s interview with Talarico originated from a January notice from the Federal Communications Commission issued by the agency’s chairman, Brendan Carr, a Trump ally who has spent his tenure weaponizing regulatory ambiguity to intimidate broadcasters. The notice warned that late-night and daytime talk shows could no longer assume they qualify for the “bona fide news exemption” from the equal time rule, a protection that has been in place since Jay Leno’s producers won it in 1996. Carr hasn’t formally repealed the exemption. He has merely threatened to — and watched as networks trip over themselves to comply with a rule that doesn’t yet exist. Colbert put it plainly on air: CBS was “unilaterally enforcing” guidance that had not been made law. No one forced their hand; they just folded.

The FCC’s lone Democratic commissioner, Anna Gomez, also called out both the network and the Trump administration. Gomez wrote on X that CBS’s decision is “yet another troubling example of corporate capitulation in the face of this Administration’s broader campaign to censor and control speech” and made clear that “the FCC has no lawful authority to pressure broadcasters for political purposes or to create a climate that chills free expression.”

Layered on top of all of this is the arrival of Bari Weiss as editor-in-chief of CBS News. Weiss built her brand at The Free Press as a contrarian voice fluent in the grievances of people who believe mainstream media has become too liberal. She was installed by David Ellison after his acquisition of Paramount and almost immediately began leaving her mark with shifts in content and reports of chaotic decision-making behind the scenes.

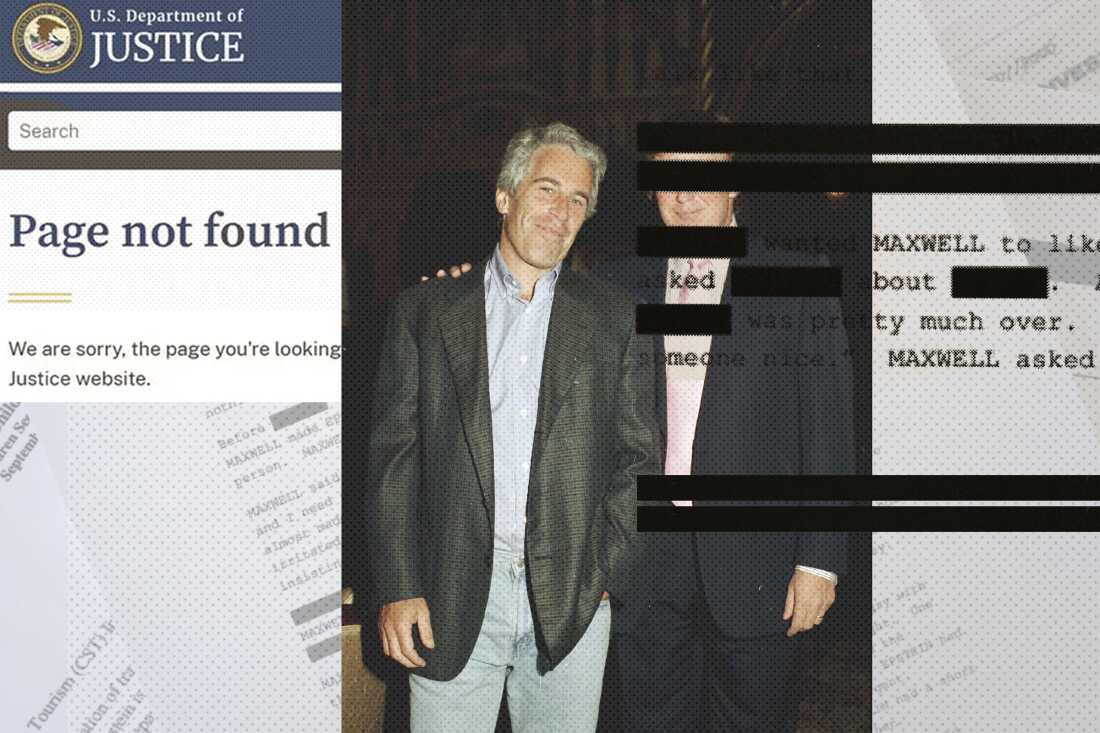

In January, Weiss announced 19 new paid contributors to CBS News with evident excitement, describing them as experts who would appear across the network’s broadcasts and digital platforms. Among them was Dr. Peter Attia, a wellness influencer and longevity podcaster with a large online following and a heterodox approach to medicine that has made him popular in right-leaning media. Three days after Weiss announced Attia’s hire, the Department of Justice released a new trove of the Jeffrey Epstein files — in which Attia’s name appeared more than 1,700 times. The emails were not ambiguous. In a June 2015 message, the wellness influencer wrote to Epstein that the worst part about being his friend was that “the life you lead is so outrageous, and yet I can’t tell a soul.” In another exchange from 2016, Attia made a crude sexual joke directed at the convicted sex offender. The files also revealed that Attia had, on at least one occasion, chosen to spend time with Epstein rather than visit his infant son, who had been hospitalized after entering cardiac arrest.

What followed inside CBS News was, according to multiple reports, a battle. Weiss refused to fire Attia because she saw it as “giving in to the ‘mob,'” while senior Paramount executives took the position that a man with hundreds of documented email exchanges with an accused child sex trafficker could not function as a credible expert contributor on a broadcast network. The situation reportedly required escalation to Ellison himself to resolve. (Notably, Weiss reports directly to Ellison — not to the head of CBS News nor to the president of Paramount.) Weiss’ reported rationale — that Attia’s “contrarian voice” was too valuable to lose — reveals that in her editorial calculus, the network’s credibility with its audience is less important than her commitment to a particular brand of heterodoxy.

This comes after Weiss infamously delayed a “60 Minutes” segment at the last minute in December that documented Trump’s deportation of migrants to the notorious CECOT prison in El Salvador. She was also reported to have privately disparaged the show’s correspondent Sharyn Alfonsi, who reported the segment, to journalists in off-the-record briefings.

Early on, Weiss also expressed interest in wooing “60 Minutes” contributor Anderson Cooper away from his full-time role at CNN to anchor the “CBS Evening News,” before she settled on Tony Dokoupil. Cooper, in the end, chose to leave CBS entirely. According to reporting from Oliver Darcy’s Status newsletter, the editorial scrutiny Weiss applied to Cooper’s reporting — including a piece on the Trump administration’s differential treatment of South African refugees that had been in progress since last year — left his producer exasperated and the timeline for the segment unclear. As one insider put it, Cooper “wasn’t comfortable with the direction the show was taking under Bari, and is in a position where he doesn’t have to put up with it.”

Cooper’s reported judgment is a devastating verdict on the Weiss era from a nationally-known and widely-respected veteran correspondent, and comes one week after producer Alicia Hastey walked out of CBS News with a damning farewell note calling the newsroom atmosphere one of “fear and uncertainty.”

We need your help to stay independent

“Stories may instead be evaluated not just on their journalistic merit,” she wrote, “but on whether they conform to a shifting set of ideological expectations — a dynamic that pressures producers and reporters to self-censor or avoid challenging narratives that might trigger backlash or unfavorable headlines.”

Cooper’s exit raises questions about the future of “60 Minutes.” Other veterans like Lesley Stahl and Scott Pelley have already spoken publicly about concerns over the state of CBS News and its changing newsroom standards. Longtime “60 Minutes” executive producer Bill Owens resigned months earlier, making it clear that he believed the program’s editorial independence was under strain. The institution is not just losing talent; it is losing the credibility built over decades that no roster of podcasters can replace.

What we are watching is the systematic dismantling of institutional independence in real time at one of the most historically significant news and entertainment corporations in America. Stephen Colbert is leaving in May. Anderson Cooper is already gone. What CBS should be asking itself is not how to manage the departure of the people who made it matter, but whether anyone left in the building still believes the mission is worth defending.

Justice Department withheld and removed some Epstein files related to Trump

Justice Department withheld and removed some Epstein files related to Trump

Heard on Morning Edition

An NPR investigation finds the Justice Department has removed or withheld Epstein files related to President Trump.

The Justice Department has withheld some Epstein files related to allegations that President Trump sexually abused a minor, an NPR investigation finds. It also removed some documents from the public database where accusations against Jeffrey Epstein also mention Trump.

Some files have not been made public despite a law mandating their release. These include what appear to be more than 50 pages of FBI interviews, as well as notes from conversations with a woman who accused Trump of sexual abuse decades ago when she was a minor.

NPR reviewed multiple sets of unique serial numbers appearing before and after the pages in question, stamped onto documents in the Epstein files database, FBI case records, emails and discovery document logs in the latest tranche of documents published at the end of January. NPR's investigation found dozens of pages that appear to be catalogued by the Justice Department but not shared publicly.

The Justice Department declined to answer NPR's questions on the record about these specific files, what's in them and why they are not published. After publication, the Justice Department reached out to NPR, taking issue with how its responses to questions were framed. Department of Justice spokeswoman Natalie Baldassarre reiterated DOJ's stance that any documents not published are privileged, are duplicates or relate to an ongoing federal investigation.

Following NPR's reporting, the House Oversight Committee's ranking member, Rep. Robert Garcia, D-Calif., released a statement about the missing files.

"Yesterday, I reviewed unredacted evidence logs at the Department of Justice. Oversight Democrats can confirm that the DOJ appears to have illegally withheld FBI interviews with this survivor who accused President Trump of heinous crimes," Garcia stated.

Democrats on the House Oversight Committee have already been investigating this allegation against the president and will now open a parallel investigation into the DOJ's decision not to release these particular documents.

Other files scrubbed from public view pertain to a separate woman who was a key witness for the prosecution in the criminal trial of Epstein's co-conspirator, Ghislaine Maxwell, who is serving a 20-year prison sentence for sex trafficking. Maxwell is seeking clemency from Trump.

Some of those documents were briefly taken down and put back online last week, while others remain hidden, according to NPR's comparison of the initial dataset from Jan. 30 with document metadata of those files currently on the Justice Department's website.

NPR does not name victims of sexual abuse.

When asked for comment about the missing pages and the accusations against the president, a White House spokeswoman told NPR that Trump "has done more for Epstein's victims than anyone before him."

"Just as President Trump has said, he's been totally exonerated on anything relating to Epstein," White House spokeswoman Abigail Jackson told NPR in a statement. "And by releasing thousands of pages of documents, cooperating with the House Oversight Committee's subpoena request, signing the Epstein Files Transparency Act, and calling for more investigations into Epstein's Democrat friends, President Trump has done more for Epstein's victims than anyone before him. Meanwhile, Democrats like Hakeem Jeffries and Stacey Plaskett have yet to explain why they were soliciting money and meetings from Epstein after he was a convicted sex offender."

The White House has previously pointed to a statement from the Justice Department that says the Epstein files contain "untrue and sensationalist claims" about the president.

In a Feb. 14 letter to members of Congress first reported by Politico, Attorney General Pam Bondi and Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche insist that no records were withheld or redacted "on the basis of embarrassment, reputational harm, or political sensitivity, including to any government official, public figure, or foreign dignitary."

First woman accuses Trump of sexual abuse

According to the newly released files, the FBI internally circulated Epstein-related allegations that mention Trump in late July and early August 2025. The list, collected from the FBI's National Threat Operations Center, included numerous salacious allegations. Agents marked most of the accusations as unverifiable or not credible.

But one lead was sent to the FBI's Washington office with the purpose of setting up an interview with the accuser. The lead was included in an internal PowerPoint slide deck detailing "prominent names" in the Epstein and Maxwell investigations last fall.

The woman who directly named Trump in her abuse allegation claimed that around 1983, when she was around 13 years old, Epstein introduced her to Trump, "who subsequently forced her head down to his exposed penis which she subsequently bit. In response, Trump punched her in the head and kicked her out."

Out of more than 3 million pages of files released by the Justice Department in recent months, this specific allegation against Trump appears only in copies of the FBI list of claims and the DOJ slideshow.

But a review of FBI case file logs and discovery documents turned over to Maxwell and her attorneys in the criminal case against her point to one place the claim could have come from — and how serious investigators took it.

The FBI interviewed this Trump and Epstein accuser four times. That is according to an FBI "Serial Report" and a list of Non-Testifying Witness Material in the Maxwell case that were also released under the Epstein Files Transparency Act.

Only the first interview, conducted July 24, 2019, is in the public database. That interview does not mention Trump.

Of 15 documents listed in a log of the Maxwell discovery material for this first accuser, only seven are in the Epstein files database. Those missing also include notes that accompany three of the interviews. The discrepancy in the file for the Trump accuser was first reported by independent journalist Roger Sollenberger.

According to NPR's review of three different sets of serial numbers stamped onto the files, there appear to be 53 pages of interview documents and notes missing from the public Epstein database.

In the first interview document, the woman discussed ways Epstein abused her as a girl and, in identifying him to investigators, showed a cropped photo of the disgraced financier. Her attorney said it was cropped because she "was concerned about implicating additional individuals, and specifically any that were well known, due to fear of retaliation."

The FBI agents noted it was a "widely distributed photograph" of Epstein with Trump.

A woman whose biographical details and description of Epstein's abuse found in the FBI interview also line up with details from a victim lawsuit. In the December 2019 filing, "Jane Doe 4" does not mention Trump, and the woman voluntarily dismissed her claims against Epstein's estate in December 2021.

Attorneys for this accuser declined to comment.

Elsewhere in the released Epstein files, someone in the FBI wrote on July 22, 2025, before the list and slide presentation were compiled, that Trump's name was in the larger case files and that "one identified victim claimed abuse by Trump but ultimately refused to cooperate."

Second accuser says she met Trump at Mar-a-Lago

The other woman whose mention of Trump made the DOJ's presentation appears in Maxwell discovery files released last month in what's known as a Testifying Witness 3500 material list.

In the first interview of six with the FBI conducted between September 2019 and September 2021, the second woman detailed how Epstein and Maxwell's abuse began while she was around 13 years old and attending the Interlochen Center for the Arts and described how, at one point, Epstein took her to Trump's Mar-a-Lago Club to meet him.

"EPSTEIN told TRUMP, 'This is a good one, huh,'" the interview report reads.

In a 2020 lawsuit against Epstein's estate and Maxwell, the second woman added that both men chuckled and she "felt uncomfortable, but, at the time, was too young to understand why."

That interview was removed from the DOJ's public files some time after initial publication on Jan. 30 and was republished Feb. 19, according to document metadata.

The Justice Department told NPR the only reason any file has been temporarily removed is that it had been flagged by a victim or their counsel for additional review.

Multiple FBI interviews with other people refer to the second woman's meeting with Trump while she was a minor and being abused by Epstein. One interview with a fleeting mention of Trump was removed from the public database and subsequently restored last week, while another interview with the woman's mother is still offline. After publication, the Justice Department said, the file required additional redactions and will be reposted soon.

In that conversation, the mother recalled hearing that "a prince and DONALD TRUMP visited EPSTEIN's house," which made her "think that if they are there then how could EPSTEIN be a criminal," according to NPR's copy of the file that was first published.

The possible omission of files that mention these women's particular allegations against the president come as the Justice Department has warned about other documents it has published in full that include what it calls "untrue and sensationalist claims" about Trump.

At the same time, the Justice Department has removed and reuploaded thousands of pages in recent weeks to fix improperly redacted victim names. That includes documents related to the allegations from these two women, who separately say they were around 13 years old when Epstein first abused them.

Robert Glassman, who represents the woman who testified against Maxwell, sharply criticized the Justice Department's handling of the Epstein files.

"This whole thing is ridiculous," he told NPR. "The DOJ was ordered to release information to the public to be transparent about Epstein and Maxwell's criminal enterprise network. Instead, they released the names of courageous victims who have fought hard for decades to remain anonymous and out of the limelight. Whether the disclosures were inadvertent or not—they had one job to do here and they didn't do it."

A DOJ spokesperson told NPR that the department is working "around the clock" to address concerns from victims and handle additional redactions of personally identifiable information that have been flagged.

"In view of the Congressional deadline, all reasonable efforts have been made to review and redact personal information pertaining to victims, other private individuals, and protect sensitive materials from disclosure," the statement reads. "That said, because of the volume of information involved, this website may nevertheless contain information that inadvertently includes non-public personally identifiable information or other sensitive content, to include matters of a sexual nature."

NPR's Saige Miller and Ryan Lucas contributed reporting.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

LINKS TO RELATED SITES

- My Personal Website

- HAT Speaker Website

- My INC. Blog Posts

- My THREADS profile

- My Wikipedia Page

- My LinkedIn Page

- My Facebook Page

- My X/Twitter Page

- My Instagram Page

- My ABOUT.ME page

- G2T3V, LLC Site

- G2T3V page on LinkedIn

- G2T3V, LLC Facebook Page

- My Channel on YOUTUBE

- My Videos on VIMEO

- My Boards on Pinterest

- My Site on Mastodon

- My Site on Substack

- My Site on Post

LINKS TO RELATED BUSINESSES

- 1871 - Where Digital Startups Get Their Start

- AskWhai

- Baloonr

- BCV Social

- ConceptDrop (Now Nexus AI)

- Cubii

- Dumbstruck

- Gather Voices

- Genivity

- Georama (now QualSights)

- GetSet

- HighTower Advisors

- Holberg Financial

- Indiegogo

- Keeeb

- Kitchfix

- KnowledgeHound

- Landscape Hub

- Lisa App

- Magic Cube

- MagicTags/THYNG

- Mile Auto

- Packback Books

- Peanut Butter

- Philo Broadcasting

- Popular Pays

- Selfie

- SnapSheet

- SomruS

- SPOTHERO

- SquareOffs

- Tempesta Media

- THYNG

- Tock

- Upshow

- Vehcon

- Xaptum

Total Pageviews

GOOGLE ANALYTICS

Blog Archive

-

▼

2026

(383)

-

▼

February

(198)

- CBS is unraveling — and it goes beyond Bari Weiss

- Justice Department withheld and removed some Epste...

- FASCIST FAILURE

- GRAND JURY

- The Truth

- TONY G TOPS A LONG LIST OF MAGATS WHO ARE PERVERTS...

- ANOTHER CRUSHING LOSS FOR TRUMP AND PIRRO WHO IS A...

- NEW INC. MAGAZINE COLUMN BY HOWARD TULLMAN

- Hey Team USA Men's Hockey, Congratulations, You Ju...

- TONY'S GOTTA GO NOW..

- DEMENTED DON

- Don’t let the media tell you this dumpster fire is...

- SAYS IT ALL...

- BIG QUESTION FOR TOMORROW NIGHT

- Trump Got Boycotted By Governors, Smacked Down In ...

- JOYCE VANCE

- EPSTEIN UPDATE

- The Decaying Legal Culture in the Defense Department

- Days after $5M donation, Trump administration back...

- Boycott the State of the Union

- Let’s take the win on tariffs.

- Kash Patel Takes a Victory Lap

- You Do Not, Under Any Circumstances, Gotta Hand It...

- STOP THE SAVE ACT

- Heaven and Hell in American Politics

- It's SOTU Time!

- Does Trump really think he can get away with this?

- The State Of The Union Is That We've All Had Enoug...

- ASHA

- Talking With Ro Khanna

- TRUMP BUTT KISSER STRIKES AGAIN

- DOWD

- HUBBELL

- FRUM

- HEATHER

- RAND PAUL

- FUCK FOX

- ROBERT HUBBELL

- HEATHER

- PAUL KRUGMAN

- BONDI BONANZA

- BORED OF SLEEP

- When White Racial Rescue Becomes a Foreign Policy ...

- NUTLICK

- He Studied Cognitive Science at Stanford. Then He ...

- HEATHER

- Please, oh please(!), send Cabinet secretaries to ...

- Stephen Colbert and the First Amendment

- QUIET PEDO

- EPSTEIN FOREVER

- Has Mass Deportation Become A Domestic Vietnam For...

- Taking Stock of the Roberts Court at 20—and the Sh...

- ROBERT HUBBELL

- TRUMP

- Epstein uber alles

- The DHS Death Spiral

- Bondi is Trump's Maxwell - Groomed by Perverts and...

- HEATHER

- THESE COMMENTS BY LYLE FASS CAME IMMEDIATELY TO MI...

- NEW INC. MAGAZINE COLUMN FROM HOWARD TULLMAN

- DAN RATHER

- THE WORST PRESIDENT IN HISTORY

- Is Artificial Intelligence the Next Great Bubble?

- The Epstein Files: The Blackmail of Billionaire Le...

- LET'S BE CLEAR - VANCE IS A CLASSLESS LYING PIG WH...

- Brace Yourself for the AI Tsunami 15.02.202622:0...

- The Bill Has Come Due

- Trump On President's Day - Rot, Failure, And Decline

- RFK JR IS CERTIFIABLE

- NOT ENOUGH

- Epstein ran the biggest sex ring ever and now Pam ...

- Marco Rubio's Munich Security Conference Speech

- The Squalor of the Epstein Class

- Insult everyone. Answer for nothing.

- The Worst President Ever

- How technology has already changed the world in my...

- Something Big Is Happening

- What Being a Billionaire Scion Taught JB Pritzker ...

- SAVE ACT IS ANOTHER MAGAt SCAM

- Pedo Protectors

- The Trump Administration Is Developing a Multi-Pro...

- A Dose of Hard Truths

- Welcome to the Voyage of the Damned

- A Fight Democrats Must Win

- HEATHER

- Excising the Cancer in Our Institutions

- Rethink what you're telling your kids.

- Worry, Don't Panic, Over Trump's Efforts to Subver...

- MORE STUPID AND OBVIOUS LIES FROM THE DEMENTED PER...

- The Friday Brief, February 13, 2026

- TRUMP

- The Nonresponse To Donald Trump

- You are no longer the smartest type of thing on Earth

- Ana Navarro torches her former drinking buddy Pam ...

- Will Progressives Stop Leading With Their Chins?

- When the Nation’s Top Lawyer Treats Ethics as Opti...

- What Trump Is the Best at, Hands Down

- CRUZ IS THIS ARROGANT CROOK, ONLY MORON WHO FITS T...

- BONDI IS A PEDO PROTECTOR AND AN EPSTEIN HOOKER AS...

- Court Absolutely Rips Hegseth Apart and *Blocks* P...

-

▼

February

(198)