US entrepreneur Howard Tullman has built one of the most successful tech incubators in the world. He explains what makes Chicago’s 1871 special… and why commercial property is ripe for disruption.

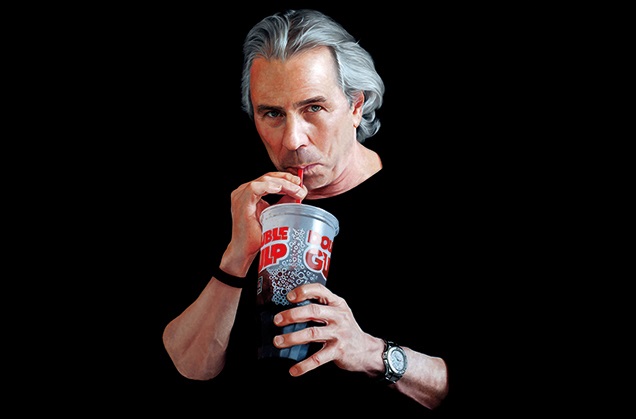

Howard Tullman has that rock-star aura that America lends to successful entrepreneurs. In casual clothing, with swept-back silver hair, he could easily pass for 15 years younger than the 70 he turned last month. He says he gets by on three hours’ sleep and fizzes with energy - thanks at least in part to the three litres of Diet Coke he confesses to drinking every day, from giant 7-Eleven ‘double gulp’ cups.

The serial entrepreneur has launched more than a dozen technology start-ups over a career spanning five decades. He is currently the chief executive of 1871, a tech incubator in Chicago’s iconic Merchandise Mart building, which he took over at the end of 2013, just over a year after it was launched. The incubator, aptly named after the year of the great fire that both destroyed Chicago and brought about its rebirth, is now recognised as not only one of the largest tech hubs in the world - but one of the best.

Tullman also regularly lectures on entrepreneurship, is a prolific blogger, avid art collector (he has more than 1,500 pieces), is writing a screenplay - and sits on a host of non-profit and civic boards.

To say he is busy is an understatement. I was lucky enough to catch up with him at the British Council for Offices’ annual conference in Chicago in May and to ask him what lessons he had for other tech incubators looking to emulate 1871’s success, why he thinks the Google office model is no longer the future - and why the traditional property agent’s days are numbered.

Before we can begin, Tullman needs some soda. He is brought a plastic cup of ice cubes and a regular can of Coke, which then sits unopened on the table - caffeine is his poison, not sugar. Instead, he crunches on an ice cube and sets about explaining the secrets of 1871’s success - one of the key elements of which, he says, was building in some real business rigour.

“One of the first orders of business was to address the fact that it was not a ‘tech treehouse’ but it was intended to be a place where we create real businesses and real jobs,” he says. “So we put in place some metrics to measure progress and we had to tell some companies that their businesses were not likely to be successful, so they either needed to change or do something else.”

An intense hothouse

The incubator runs more than 75,000 sq ft in the Merchandise Mart - a 3.5m sq ft art-deco behemoth that is the largest office building in the US, other than the Pentagon - and will expand into a further 50,000 sq ft of space later this year. It is now home to more than 325 early-stage, high-growth digital start-ups, and around 75 businesses have graduated (which generate a collective revenue of around $26m (£17m), have raised around $16m in capital and created about 1,700 jobs).

Work space at 1871

Prospective start-ups have to pitch to be a member of the hub - where fees range from $150-$450/month - and competition is fierce. “It’s not really a community centre,” says Tullman, crunching on another ice cube. “We don’t take everybody - we actually form a conclusion as to whether we think they have a realistic prospect of being successful and if we don’t think they do then we don’t admit them.”

Tullman also put in place some industry-specific accelerator programmes within 1871 in key areas, such as real estate, education, technology, food and financial technology - a move he says is crucial when building an incubator.

“You have to figure out that you can’t be all things to all people, so I think you have to say ‘here are the three or four areas that we are going to have expertise in’ - and that has to be credible. So, if you’re in Washington DC, I think you want to have an incubator which has an expertise that is unique to how you deal with the federal bureaucracies. I mean, someone in Miami just isn’t going to open something like that.”

He says 1871 also worked to boost its educational offer, by offering business and technology programmes to its members to help them to fill gaps in their knowledge, experience and skills.

“We regard the education that we provide as supplementary to the basic job, and the basic job is helping them to build a business, grow it, raise additional financing, help them with technology issues they’re going to encounter, help with regulatory issues and eventually send them on the way to be a sustainable business,” he says.

“You have to make a commitment to more than real estate - you have to make a comprehensive commitment to resources; you have to figure out how to connect to the universities, to the venture community, to the city or state wherever you are, so all of that is present, because those are all aspects of the successful development of these businesses.”

The art-deco Merchandise Mart building

But unquestionably, a major part of the success of the not-for-profit, which receives funding through corporate donors and city hall as well as its membership fees, is also its location in the Merchandise Mart, which is so big it has its own zip code. The building, which used to be known for the interior design showrooms, has rapidly evolved into a major tech cluster. Around 1m sq ft of space is now occupied by technology businesses, including Google-owned Motorola Mobility, which moved into 640,000 sq ft of space last year - an area equivalent to around 10 football pitches - after relocating from the north Chicago suburbs.

Tullman says the sheer size of the building and volume of visitors - it attracts 20,000 people a day - helps spark innovation. “All the synergies and happy accidents that stimulate innovation and change through new ideas - the building makes a lot of that possible,” he says. “We have our own rail station in the building, we have our own post office, we have more than 25 restaurants - it’s a unique situation.”

In many ways, 1871 looks like a fairly typical trendy office, with raw concrete, exposed services and ‘hip’ furnishings (albeit all recycled from around Chicago) - but Tullman says the space is rapidly evolving and they are now introducing more closed ‘traditional’ office spaces. “We’re getting rid of the open-plan office concept - we’ve got video that indicates that when people wanted to do anything serious or were trying to concentrate they got up and moved. And when they wanted to meet as a group they moved because the other people shushed them - so they needed to have a space. So we’re going to have some open areas, but we’re going to have a lot more ‘identity areas’: closed areas, conference areas, phone rooms.”

It’s not appealingin a 5,000 sq ft space to have a ping-pong table with people screaming and enjoying themselves

He believes this is also the way the commercial office world will move, as occupiers increasingly realise open plan may not actually be the best thing for their workers - and reduces productivity. “Open plan is cheap and landlords love it, but workers increasingly find it very disruptive. We’re seeing that the Google model just doesn’t work particularly well - it’s not successful,” he says.

“The Google model was that no engineer should have to walk more than 200ft to get food - just some crazy arse thing that they decided - but what you get is micro-kitchens that don’t bring people together and don’t have a quality offering and just result in a bunch of wear and tear and maintenance.”

The key is to offer quality work spaces that are not “novelties” but based around addressing the lifestyle needs of the new generation of millennial workers - such as bike rooms and showers - as well as providing the very best tech offering, such as super bandwidth, unparalleled connectivity for phones and top-grade speakerphones for conferences. “Nobody wants to go into a conference room and spend 20 minutes figuring out how to get the technology to work. They want to walk into a room and press one button and engage with somebody in a Skype conference, end of story - and if they can’t, they’ll do it on their own phone with FaceTime or something else.

“If companies go down the Google model route they’ll quickly become passé - they’ll be focused on food and a couple of other things that are not significant. It’s not appealing in a 5,000 sq ft space to have a ping-pong table with people screaming and enjoying themselves - after hours that’s fine, but during the day people want to work.”

Primed for disruption

The commercial property industry itself is also set for upheaval, believes Tullman. His thinking is partly informed by the real estate tech start-ups that are being incubated in 1871, where there is a dedicated real estate accelerator programme. Businesses in the programme include: CondoGrade, which assigns grades to condominium associations based on their financial health; HerbFront, which helps medical cannabis entrepreneurs connect with real estate owners and provides zoning and mapping tools; PeerRealty, which gives middle-market investors access to developers in hope of creating investment opportunities; and Megalytics, which aggregates third-party data in real time to give lenders a hand with risk assessment.

Tullman speaking at 1871

The start-ups are all focused on applying tech to the real estate industry, which Tullman says is ripe for innovation and disruption. “Real estate is going to be very challenged. The business of real estate has depended since the beginning of time on the inequality of information - and not good information. So, if you were a broker and you knew some space was becoming available, the last thing you would want to do is share that with other brokers, because they may have clients who would compete with you.

“So all of that - that basic premise that I’m a trained expert and I know something the market doesn’t know - will be the largest shift. In a relatively short period of time, we’re going to have perfect information and we’re going to have degrees of transparency that are going to completely change the real estate business, which is based right now

on relationships.

on relationships.

“Relationships won’t go away, but the client will say: ‘I don’t want only you exposing my property to only these four people, because there might be somebody in China who will pay 10 times that to buy my property and we need to take advantage of the fact that there are new entrants into these markets.’ That will be one huge change.”

So is he predicting an end to the commercial property agent, as we know it? “Yes,” is the emphatic answer, and with that, Tullman crunches on another ice cube and slaps the table. “We done?” he asks, jumping up as his mobile rings. And then he’s off, racing to his next meeting - and presumably a hit of Diet Coke - and leaving much for the property world to digest.

- Property Week was media partner at the British Council for Offices’ annual conference in Chicago