Earlier this week, my friend and colleague John Sipher sent me a thoughtful piece he wrote about the Epstein files, arguing that the dumping millions of documents without any way of sorting or filtering the content holds the potential to further erode the legitimacy of the justice system. He writes:

The proper place to assess this kind of material is inside a professional justice system, where trained investigators and prosecutors can evaluate credibility, corroborate claims, discard dead ends, protect victims, and bring charges only when evidence and law justify it. A mass release does the opposite. It turns investigatory material into a public scavenger hunt, where the loudest interpretation wins, and where “being mentioned” becomes “being guilty.”

Given our shared intelligence backgrounds, I get where he is coming from. Those of us who have worked in top secret arenas with classified, national security information can get worn down by conspiratorial thinking, when we know how these decisions were actually managed behind the scenes and the harm that might result from disclosing national security secrets. In these cases, I would probably agree with him that the internal processes that are were in place in these agencies did an overall good job in balancing the need for transparency and public accountability with national security.

The problem with applying that perspective here is that the Epstein files don’t implicate national security. More importantly, the one thing we do know is that the system Sipher describes — where prosecutors and agents sift through evidence and make decisions on accountability — broke down when it came to Epstein, and even failed completely in the case of the 2008 “sweetheart deal” that allowed him to walk free for another eleven years. Which necessitates a new mechanism for accountability.

There is an additional problem, which I highlighted in my “complicity cheat sheet” for the Epstein files that I wrote last month: The criminal justice system is actually a poor vehicle to address accountability in a sprawling network where people facilitated criminal activity — even if they didn’t participate in it themselves — by lending social legitimacy, signaling personal approval and even admiration, or choosing to turn a blind eye. As Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche put it earlier this week, “It’s not a crime to party with Jeffrey Epstein.”

Exactly. That’s the problem.

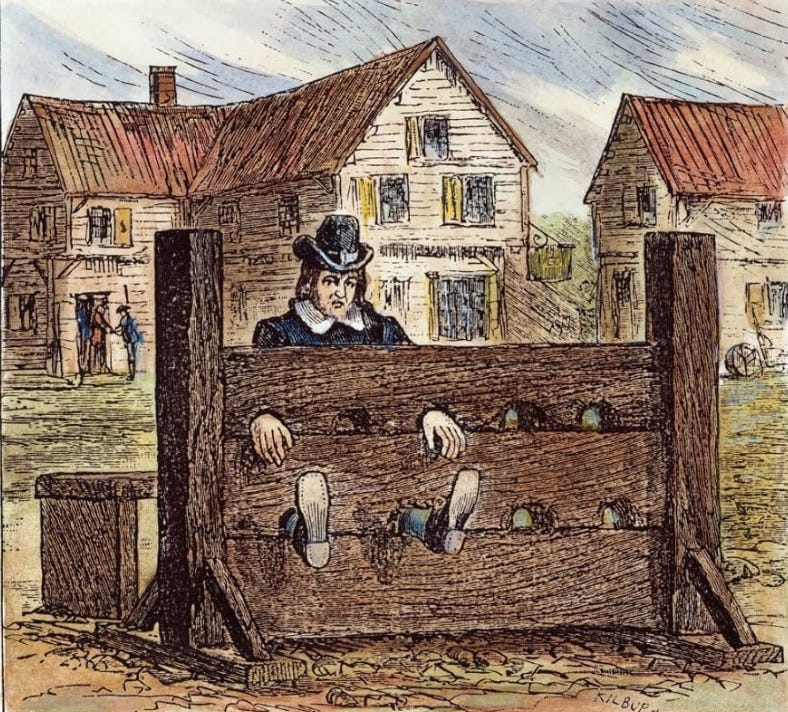

Enter “shame sanctions.” In the world of criminal justice, shame sanctions refer to a category of penalties that are designed to publicly stigmatize people for their wrongdoing as a way of forcing individual accountability and deterring similar behavior from others. You probably remember Hester Prynne from your high school American literature class, who was forced to wear the scarlet letter “A” on the front of her dress for committing adultery. That’s a shame sanction. As this University of North Caroline article notes, other, more contemporary shame sanctions include things like:

A DWI offender [being] ordered to place an identifying bumper sticker or special license plate on his or her car, or to wear a special bracelet;

Men convicted of soliciting prostitutes [being] required to have their names and faces displayed on a local access television program popularly known as ‘John TV’;

A shoplifter required to wear a court-provided t-shirt reading ‘My record plus two six-packs equals four years.’

These are all examples of a type of shame sanction that involves communicating the nature of a person’s transgression to the public, fittingly categorized as “public exposure” sanctions. (Other forms of shame sanctions include “debasement,” such as ordering a slumlord to stay a night in one of his rat-infested units (this really happened), and “apology,” which is pretty much exactly that: making someone take accountability in writing, to their victim.) The purpose of shame sanctions is to use the threat of social stigmatization to reinforce norms and deter others from engaging in similar behavior in the future.

The release of the Epstein files is basically a public exposure shame sanction. And the norm it is reinforcing through the social stigmatization is: Partying with a guy who is obviously into nubile girls may not be a crime, but it’s morally repugnant and makes you unfit to hold positions of trust or high social status.

We’ve seen this norm reinforced already. At Harvard University, Larry Summers, the university’s former president (!), was forced to step down from his teaching position. Just this past week, Brad Karp, the chairman of Paul Weiss, a major New York law firm (and the first to cave to Trump’s executive orders targeting law firms), stepped down because of the ties that the Epstein files revealed.

The Brad Karp revelation reveals another reason that the release of the files is so important, given the current political context: If only the Trump administration is aware of who is in the files, that is enormous leverage that can be used against the very powerful people in the files to comply with Trump’s increasingly unhinged demands. I personally have to wonder whether knowing that trump could “out him” drove Karp’s decision not to fight the executive order (which was quickly slapped down in court when other firms did). It’s why the ongoing redactions of individuals who are clearly complicit to some degree in Epstein’s activities are not only in violation of the law, but pose a potential threat to the rest of us since they control some of the most important and powerful companies and institutions in the world.

Even if it were functioning robustly and with integrity, I don’t think any of these people could, or would, be charged with a crime. And I should add that I wouldn’t want the Justice Department to make a decision, on its own, to release investigative files just to embarrass individuals who don’t meet the threshold to be indicted — I think we can see the potential for abuse that would create. That’s why the process used to create the transparency here — bipartisan agreement by legislators who are directly accountable to the people — matters. This “punishment,” created by legislators through a fair and representative process, is as legitimate as one given by a court.

The Epstein files are precisely the kind of thing that we couldn’t leave to the justice system to sort out, because what allowed it to happen was the reassurance Epstein got from so many people who had an awareness of his activities that they would keep his secret. Sunlight, and shame, is the only antidote for that.