150 days of Kavanaugh stops, and it just keeps getting worse

Kavanaugh stops would always be bad. As a tool in the Trump administration's authoritarianism arsenal, they are worse. The consequences are everywhere.

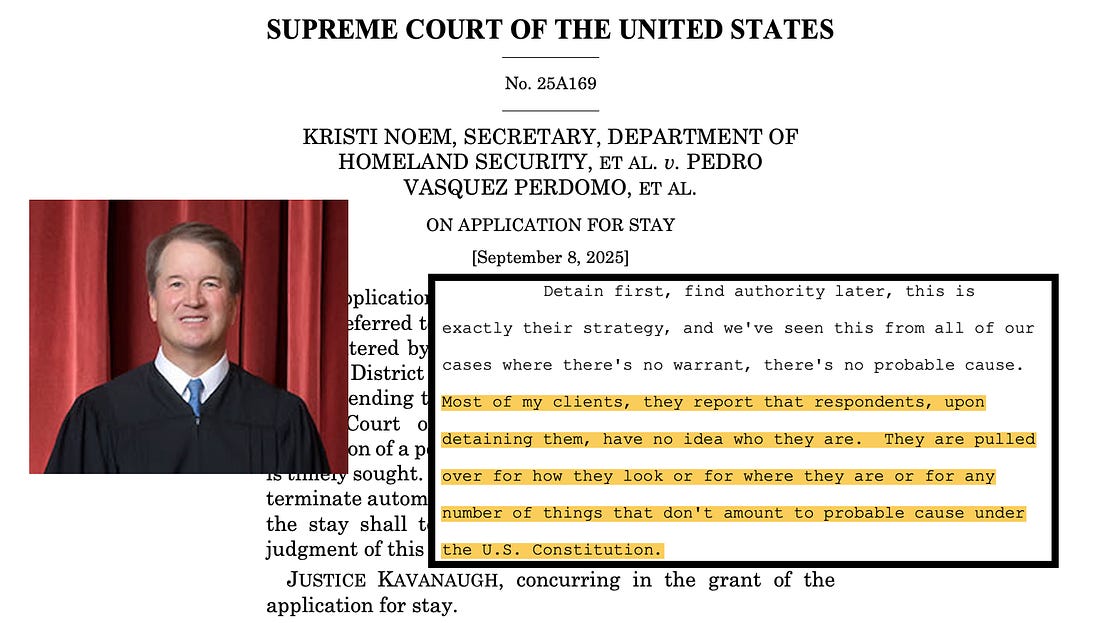

In December, Justice Brett Kavanaugh sought to use the National Guard case out of Illinois to blunt the impact of the September order from the U.S. Supreme Court that allowed what have become known as Kavanaugh stops.

Kavanaugh tried to use a footnote in his opinion in the National Guard shadow docket order to reframe part of an earlier opinion he wrote in Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo, another shadow docket order.

It has not mattered.

In fact, all evidence suggests that things are just getting worse.

The Trump administration’s extremist immigration enforcement efforts led to an order over the summer barring the federal government from racially profiling Latinos in low-wage jobs for immigration stops. The Supreme Court, over the dissent of the Democratic appointees, rejected the district court’s ruling, allowing the stops in a September 8 order.

It was in that order that Kavanaugh insisted that, “as for stops of those individuals who are legally in the country, the questioning in those circumstances is typically brief, and those individuals may promptly go free after making clear to the immigration officers that they are U.S. citizens or otherwise legally in the United States.“

It quickly became clear that Kavanaugh’s statement was not reflected in the reality of America under President Donald Trump’s authoritarianism.

At 50 days and 100 days, I covered some of the stories that show the reality — and my questions submitted to Kavanaugh about whether he stood by his statement.

We are now 150 days since the U.S. Supreme Court unleashed this racist enforcement tool, and the consequences are everywhere.

On Tuesday, in the midst of Operation Metro Surge, lawyers on both sides of ongoing habeas litigation in Minnesota bluntly acknowledged what the Supreme Court permitted the Trump administration to do.

As Kira Kelley, a lawyer with Climate Defense Project who has been representing people challenging their detention, explained to the court:

Detain first, find authority later, this is exactly their strategy, and we’ve seen this from all of our cases where there’s no warrant, there’s no probable cause. Most of my clients, they report that respondents, upon detaining them, have no idea who they are. They are pulled over for how they look or for where they are or for any number of things that don’t amount to probable cause under the U.S. Constitution.

Julie Le, the lawyer who was representing the Trump administration in court and had worked for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement before the surge, essentially acknowledged the same:

I share the same concern with you, Your Honor. I am not white, as you can see. And my family’s at risk as any other people that might get picked up too, so I share the same concern, and I took that concern to heart. But, again, fixing a system, a broken system, I don’t have a magic button to do it. I don’t have the power or the voice to do it. I only can do it within the ability and the capacity that I have.

I sent a request for comment on Wednesday to Kavanaugh through the Supreme Court’s Public Information Office about the transcript out of Minnesota, highlighting Kelley’s comment.

The result of this in Minnesota is, as Law Dork covered earlier this week, habeas petitions being granted — and often. As one of the lawyers behind those petitions, Kelley knows:

I think this would be a different story if these habeas petitions were frivolous, but we’re filing so many because there are just so many people being detained without any semblance of a lawful basis.

Beyond the direct result of Vasquez Perdomo, Law Dork has also reported on how the Trump administration — or, at least, Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem — is expansively using that shadow docket grant of authority to justify stopping virtually anyone.

As I was preparing this report, Wired’s Dell Cameron and Maddy Varner raised a further concern, publishing an alarming report on Thursday detailing one way DHS is using new technology:

Despite DHS repeatedly framing Mobile Fortify as a tool for identifying people through facial recognition, however, the app does not actually “verify” the identities of people stopped by federal immigration agents—a well-known limitation of the technology and a function of how Mobile Fortify is designed and used.

This is all the more alarming in light of the way the administration is expansively using that shadow docket grant of authority. As Cameron and Varner note:

DHS—which has declined to detail the methods and tools that agents are using, despite repeated calls from oversight officials and nonprofit privacy watchdogs—has used Mobile Fortify to scan the faces not only of “targeted individuals,” but also people later confirmed to be US citizens and others who were observing or protesting enforcement activity.

This is the world Kavanaugh and his fellow Republican appointees on the Supreme Court have allowed.

Does Kavanuagh still think he was correct when he wrote, “[A]s for stops of those individuals who are legally in the country, the questioning in those circumstances is typically brief, and those individuals may promptly go free after making clear to the immigration officers that they are U. S. citizens or otherwise legally in the United States,” in light of all that we now know?

As with my prior requests at 50 and 100 days, I have heard nothing from the justice.

If I do hear from Kavanaugh, I will let you know.