Monopoly Round-Up: The Slow Death of Banking in America

Crypto interests came after the local banker last week in a bitter Congressional fight. They didn't win, but it's not over. Plus, the "Mamdani effect" is real, and Canada aligns with China.

Lots of monopoly-related news this week, as usual. A Canadian deal with China shows the world turning against America, Trump nominated a billionaire to run his antitrust policy at the Federal Trade Commision, and Mayor Zohran Mamdani seems to be off to a great start. And a lot more..

But before getting to all of that news, I want to highlight an important moment on Capitol Hill last week that could dictate the future of finance in America. On Thursday, the Senate Banking Committee abruptly canceled its meeting, known as a mark-up, to write little-noticed legislation to deregulate the financial system. And the reason is that two of the more powerful forces in D.C. - the banking lobby and the new MAGA-powered crypto world - came into conflict. The result, so far, is a stalemate.

I haven’t written about crypto for a few years, because there’s not much to say beyond “they did a lot of bribes in a bribe-prone system.” But depending on what happens next, we could be looking at the end of an iconic American figure, the local banker, and his or her replacement with something very different. The context of the legislative fight is, as you see in lots of other areas, the decline of the productive institutional fabric of America.

Culturally speaking, banks have a weird place in America, as they are the institutions that control permission to use resources. The endless number of bank heist movies, often with plucky burglars as heroic figures telling bank customers they needn’t worry because it’s not their money at risk, suggests that there’s a lot of skepticism of financial power in general. But there are two types of bankers, the generous local elite and the extractive beancounter. These represent a traditional populist vs oligarch framework.

Take the holiday classic film It’s a Wonderful Life. It’s about a small town banker named George Bailey, played by Jimmy Stewart. Bailey’s help financing useful things in Bedford Falls, like houses and businesses, contrasts with the avaricious Harry Potter, who is a stand-in for Wall Street.

There’s a reason for these cultural totems. Americans have always understood that distant control of credit is dangerous, the theme of movies such as Wall Street, Margin Call, and The Big Short. They also see that local control of credit and payments is key to self-sufficiency. Local banks uses to be, and to some extent still are, the powerhouse of American cities and towns.

That said, there have always been a variety of financial institutions to serve different kinds of customers, including large corporations. There are three kinds of banks in America, the small bank, the regional bank spanning a few states, and a few dozen national mega-banks. Local banks, a la George Bailey, are more efficient with better service and more commercial lending. According to the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, roughly half of U.S. assets were held in small banks, which did most of the productive lending. In 2020, small and regionals held just 17% of industry assets, but offered 46% of bank lending to new and growing businesses.

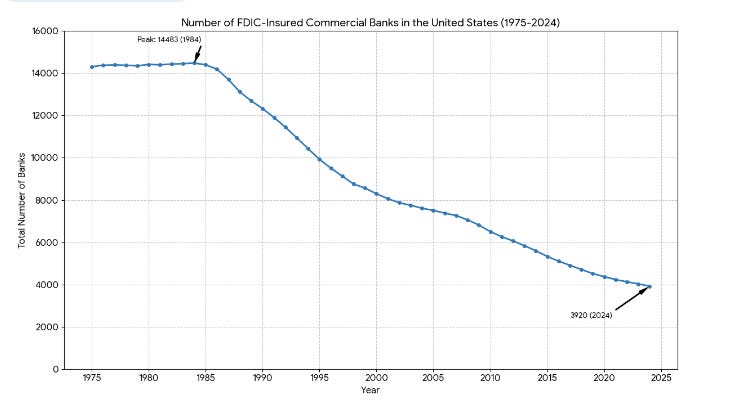

In the post-war era, this mix of banking was relatively stable, with roughly fourteen thousand local banks and thrifts serving as mortgage and commercial lenders, and check clearing institutions. But in the early 1980s, policymakers sought to consolidate the sector, enacting a series of deregulatory laws to encourage bank failures and mergers. The result is that today we have fewer than four thousand banks, and by the end of the Trump administration, we may have fewer than a thousand.

Of course, the world isn’t the same as it was forty five years ago. Since the 1980s, finance has changed. We are a capital markets driven economy, not a bank-driven one, and we use credit cards not checks, apps and ATMs more than branches. Bailouts have replaced proactive regulation, and we now have four giant Too Big to Fail banks that span multiple lines of business from investment banking to brokerage services. But local economies still depend on local banks, and there are fewer and fewer of them.

The business of a bank is pretty simple. Banks make loans, by either lending directly to consumers or business, or by buying commercial or government bonds. They finance those loans with deposits, usually from local customers who want a safe place to keep their money and earn a bit of interest. Deposit are guaranteed by the government, so they are as good as cash. The spread between what they pay for deposits and what they from loans or bonds is their profit margin.

Banks like getting deposits from customers, because it’s cheap. On the other side of the ledger, banks make loans. There’s a myth that banks accept deposits and make loans with those deposits. That’s not true, banks first make loans and then find the deposits to finance those loans. If they can’t get enough deposits from local customers to match their loans, they will acquire higher cost deposits in various money markets. If they have deposits and not enough loans, they can just put their extra cash at the Fed, and make a guaranteed 3.6%.

Profits are easy, as the Fed gives high rates to banks while banks offer low returns to depositors. This dynamic is particularly the case for the largest banks. JP Morgan, for instance, made $96 billion in net interest margin in 2025.

Banking is a great business, because mostly you pay customers a small amount for the use of their money, and get the government to guarantee you a profit. You can make more if you actually do the work to lend money, but you don’t have to.

In return for this easy profit via a government safety net, bankers accept regulation. As the brilliant scholar Saule Omarova notes, the best way to understand banks is as franchises from the government. Bankers safeguard the nation’s money and payments system, and are well-paid for it, but it’s fundamentally a public and not a private duty. That’s why there are banking charters from the state.

The rise of crypto parallels the consolidation and corruption of banking. From the 1980s onward, small town bankers, like everyone else during the neoliberal era, became heavily oriented around removing rules against speculation and froth. The low interest rate environment of the New Deal gave way to a high interest rate world, and that put enormous pressure on the balance sheets of bankers who had lent money more cheaply. That, plus the turn of the Democrats away from protecting small towns in favor of consumer rights, led to a sharp anti-government sentiment among local bankers.

Over time, the banking lobby, which was fragmented into many parts, unified and became part of the Reagan-Bush GOP establishment. Bankers of all stripes get their free money from the government, they lend money to businesses and consumers, they overcharge on credit cards and overdraft fees, they spend some of their free money on lobbyists, and they hate on regulators and disinterested liberals. That’s what they do. It’s who they are. And it’s worse the closer you get to D.C. Since the financial crisis of 2008-2010, bank lobbyists have become solidly right-wing advocacy organizations, instead of advocates for their members. They are now just partisan Republicans, culturally as conservative as soybean farm owners or white evangelical Christians.

The financial crisis shook the banking establishment, as it did everyone else. The bailouts created disillusionment, which paved the way for libertarians to create a new unregulated payments and speculative regime, seemingly untethered to the state. While anti-monopolists argued for a renewal of public institutions to tamp down on concentrations of wealth and power, the crypto world went the opposite way, arguing that it was the very existence and power of public institutions that led to the crisis in the first place.

Crypto was ideological, at first framed around utopian rhetoric and the blockchain. Unfortunately, there were no actual real use cases for productive ends, it was entirely a way of scamming or speculating without rules. During the 2010s, when the Federal Reserve kept interest rates at zero and engineered a set of bubbles, crypto was one of the more prominent ones. In 2021, I wrote an article titled “Cryptocurrencies: A Necessary Scam” describing the ideological goal of crypto.

Fortunately, regulators kept crypto hived off from the real economy, so as the bubble blew up, it didn’t much matter. In 2022, when Sam Bankman-Fried and a host of crypto institutions collapsed in an orgy of fraud and leverage and money laundering and sanctions evasions, crypto seemed to be over. But it wasn’t, because of the power of the banking lobby, the weakness of Joe Biden’s administration, and the general pro-deregulation consensus in Congress.

Biden never made a decision about his views on finance or political economy. His administration’s financial policy was led by Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, who was generally fine with crypto. His Commodities Futures Trading Commission was run by a crypto-friendly former Senate staffer named Rostin Behnam and his FDIC Chair Martin Gruenberg, was feeble. Biden did nominate crypto foe Omarova to be the head of the Comptroller of the Currency, but local bankers lobbied the Senate to block her, with a unified Republican opposition and a few corporate Democrats. A weak Yellen subordinate Michael Hsu took that spot. That same year, Biden renominated Fed Chair Jay Powell, who got confirmed.

The main opponent of crypto was Gary Gensler at the Securities and Exchange Commission, and he fought aggressively, but the courts rolled back his attempts to litigate in the sector. By late 2023, the price of bitcoin recovered. As it became clear that the scam economy could continue with enough political support, venture capitalist Marc Andreessen and Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong organized hundreds of millions of dollars of campaign spending. No one in politics had ever seen anything like Fairshake PAC, stocked with cash and run by feral operatives who were pretty open about their pay-to-play view of how Congress works. They ran over everyone in their way, in effect buying Congress and the regulatory apparatus behind Trump.

After Biden, the crypto industry had immense political leverage over a supine Congress and a friendly administration. Concerns over things like consumer protection ended, of course, but even more “serious” things like worries over national security and sanctions evaporated. Trump pardoned the Binance CEO Changpeng Zhao, and no one cared any longer that crypto was used to funnel money to Hamas and Venezuela.

The narrative around crypto changed, as crypto proponents dropped their naive ideological arguments. Industry proponents no longer argued there’s anything innovative, or that crypto is important for payments or any other purpose. It’s purely a mechanism to speculate. And the industry ended its commitment to a stateless approach. The trading side of crypto attacked stock market regulations, while the banking side demanded access to the banking franchise, including bank charters, access to the Federal Reserve safety net, and so forth. They started claiming they are bank-like, only better, and that the current banking order is lazy and protected by regulation.

And that brings us to the legislative fight last week. A few months ago, Congress did its first set of favors for the crypto industry, passing the Genius Act, which allowed for companies to issue “stablecoins,” which is to say, they can take dollar deposits as long as they back those deposits with actual dollars. However, they were mostly barred from paying interest on stablecoins. And the payment of interest on deposits is really key, because that’s what would allow stablecoin issuers and crypto exchanges to compete with banks over those cheap customer deposits that enable profits. It is an existential problem, not for the JP Morgan’s of the world, as they are so big it doesn’t matter, but for the rest of the banking sector, the local and community guys.

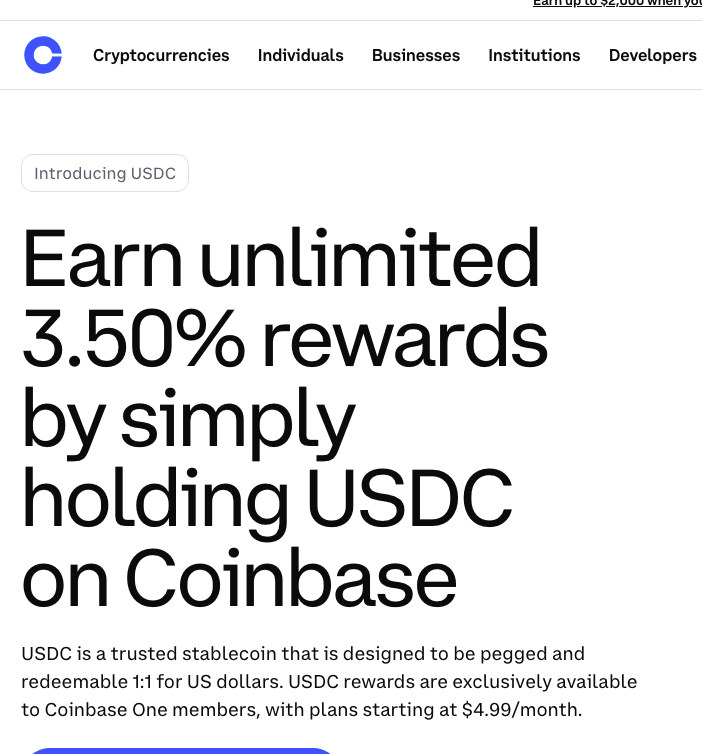

The most aggressive crypto firm, Coinbase, sort of offers interest on deposits, with what are called “rewards.” By calling them rewards instead of interest, Coinbase is trying to create a loophole in the Genius Act. But it’s a grey area, at best, and regulators could crack down.

The next piece of legislation pushed by the crypto world was called the Clarity Act, which has a number of elements, some of them involving rules around speculation. If it passes, we can expect very little regulation of the stock market, anti-money laundering, or insider trading going forward. But the fight that led to the cancelation of the markup of the Clarity Act is whether “rewards,” aka interest on deposits, are legal. Enter the banking lobby.

Community and regional bankers are not used to fighting with conservatives, because they haven’t had to. They did block liberal lawyer Omarova from becoming the bank regulator at the Office of Comptroller of the Currency. But they certainly aren’t used to dealing with feral and weird crypto MAGA online influencers with billions of dollars. That doesn’t make sense to them. And it should have been obvious that they were in the crosshairs of the crypto industry; the Federal Reserve just launched a rulemaking to give crypto a mini bank charter, which should scare the hell out of the local banks.

But they finally have started to get in gear, pointing to a Treasury report saying that $6.6 trillion of deposits might leave the banking system if crypto companies could pay interest on stablecoins. The Independent Community Bankers Association, the trade group for local bankers, mobilized its members against stablecoin rewards.

Much of the crypto world doesn’t care about stablecoins or banking; they are interested in removing the rules regulating speculation and gambling. For them, it’s a securities law matter. But for Coinbase, which makes roughly a billion dollars in revenue with stablecoins, that part of the bill does matter. And so Brian Armstrong pulled his support for the bill on the eve of the markup. There’s something a bit odd about Coinbase’s opposition, since they got 95% of what they wanted, and everyone else is fine with the legislation. But I don’t want to speculate too much on motivations, the point is Armstrong was unhappy with the final bill.

It’s not clear what happens now. The Senate Banking Committee has put enormous time and effort into this legislation, at the behest of crypto donors. But it really is an zero sum fight. If crypto exchanges can pay interest or rewards on stablecoins, then local banks lose their deposit base. If crypto exchanges can’t, then they won’t get access to cheap deposits. While Senators are desperate for some sort of compromise, it doesn’t look like there is one. Someone has to win and someone has to lose.

This battle is one where there is no good guy, but if there’s someone who is less bad, it would be the local bankers. They at least do lend into communities, and are subject to real regulation. Crypto is a disaster, and if we integrate crypto into the real economy, they will eventually demand their own bailout. But the critique that banks don’t pay much in interest on accounts is accurate. Furthermore, the credit card business is a bloated monopolistic mess. Still, those problems are largely about the Too Big to Fail banks, not the local guys, and the TBTF banks will be fine regardless.

Honestly, I’m exhausted by the question that we are forced to answer in this fight. Should credit allocation and payments be controlled by a set of lazy right-wing bankers who hate government, or a hungrier and deeply corrupt group of crypto scammers? It would be nice to have an alternative to those two interest groups. And eventually, we will, since it’s becoming clear that the state will have to take a much bigger role in credit allocation. But for now, the fact that crypto finally got stopped, at least temporarily, by the banking lobby, well at least it’s funny. And it does show how checks and balances are useful even when everyone involved is deeply flawed.

At this moment, I’ll take what I can get.

And now, the rest of the monopoly round-up news. Trump nominated a controversial billionaire to become a new antitrust and consumer protection enforcer at the FTC and his DOJ antitrust enforcers have been banned from speaking publicly. Plus, his belligerence finally had a real cost, as Canada explicitly allowed imports of Chinese electric vehicles in return for China importing more canola oil. This move will have the long-term effect of destroying the North American auto supply chain and likely allowing the Chinese to monopolize the global industry.

That said, there was one serious bright spot this week. There’s now something called “The Mamdani effect” as landlords are cleaning up their act in NYC after a brilliant start to the new mayor’s term. Plus a lot of Hollywood drama as Netflix co-CEOs disagree on their reason for acquiring Warner, and pro-private equity ex-Senator Kyrsten Sinema faces a lawsuit on how she plied a security guard with the rave drug molly and slept with him.

Oh, and the Supreme Court did something good on antitrust. For real. Read on for more, after the paywall...