Justice Department withheld and removed some Epstein files related to Trump

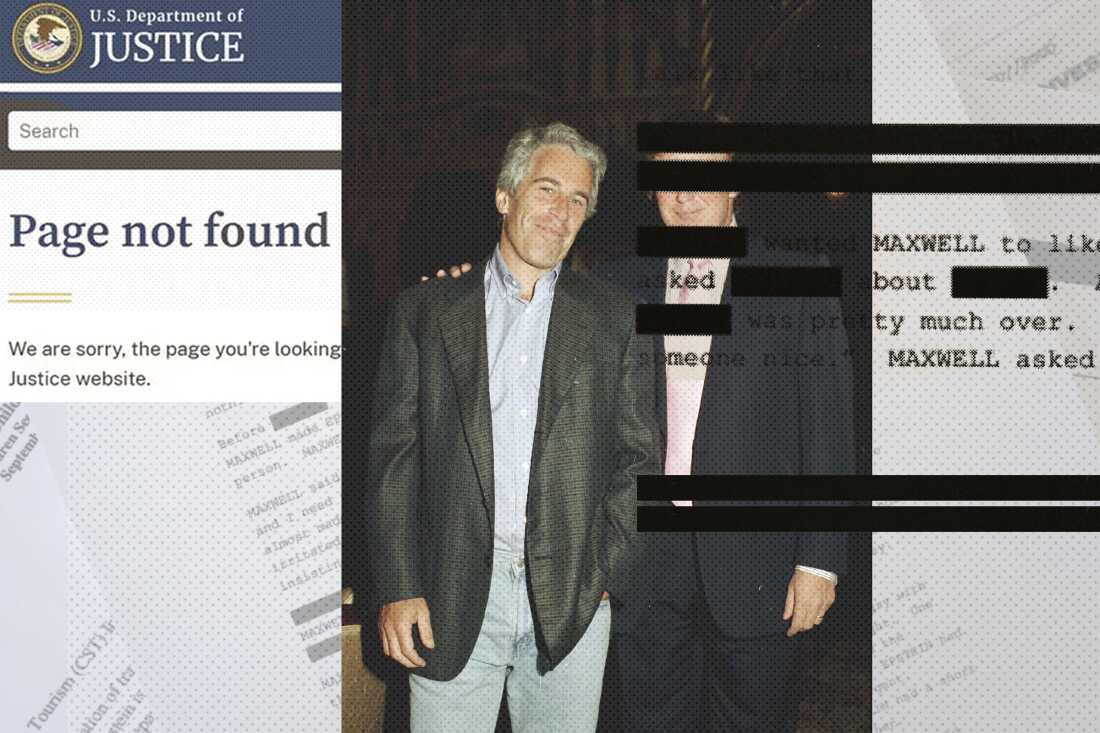

The Justice Department has withheld some Epstein files related to allegations that President Trump sexually abused a minor, an NPR investigation finds. It also removed some documents from the public database where accusations against Jeffrey Epstein also mention Trump.

Some files have not been made public despite a law mandating their release. These include what appear to be more than 50 pages of FBI interviews, as well as notes from conversations with a woman who accused Trump of sexual abuse decades ago when she was a minor.

NPR reviewed multiple sets of unique serial numbers appearing before and after the pages in question, stamped onto documents in the Epstein files database, FBI case records, emails and discovery document logs in the latest tranche of documents published at the end of January. NPR's investigation found dozens of pages that appear to be catalogued by the Justice Department but not shared publicly.

The Justice Department declined to answer NPR's questions on the record about these specific files, what's in them and why they are not published. After publication, the Justice Department reached out to NPR, taking issue with how its responses to questions were framed. Department of Justice spokeswoman Natalie Baldassarre reiterated DOJ's stance that any documents not published are privileged, are duplicates or relate to an ongoing federal investigation.

Following NPR's reporting, the House Oversight Committee's ranking member, Rep. Robert Garcia, D-Calif., released a statement about the missing files.

"Yesterday, I reviewed unredacted evidence logs at the Department of Justice. Oversight Democrats can confirm that the DOJ appears to have illegally withheld FBI interviews with this survivor who accused President Trump of heinous crimes," Garcia stated.

Democrats on the House Oversight Committee have already been investigating this allegation against the president and will now open a parallel investigation into the DOJ's decision not to release these particular documents.

Other files scrubbed from public view pertain to a separate woman who was a key witness for the prosecution in the criminal trial of Epstein's co-conspirator, Ghislaine Maxwell, who is serving a 20-year prison sentence for sex trafficking. Maxwell is seeking clemency from Trump.

Some of those documents were briefly taken down and put back online last week, while others remain hidden, according to NPR's comparison of the initial dataset from Jan. 30 with document metadata of those files currently on the Justice Department's website.

NPR does not name victims of sexual abuse.

When asked for comment about the missing pages and the accusations against the president, a White House spokeswoman told NPR that Trump "has done more for Epstein's victims than anyone before him."

"Just as President Trump has said, he's been totally exonerated on anything relating to Epstein," White House spokeswoman Abigail Jackson told NPR in a statement. "And by releasing thousands of pages of documents, cooperating with the House Oversight Committee's subpoena request, signing the Epstein Files Transparency Act, and calling for more investigations into Epstein's Democrat friends, President Trump has done more for Epstein's victims than anyone before him. Meanwhile, Democrats like Hakeem Jeffries and Stacey Plaskett have yet to explain why they were soliciting money and meetings from Epstein after he was a convicted sex offender."

The White House has previously pointed to a statement from the Justice Department that says the Epstein files contain "untrue and sensationalist claims" about the president.

In a Feb. 14 letter to members of Congress first reported by Politico, Attorney General Pam Bondi and Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche insist that no records were withheld or redacted "on the basis of embarrassment, reputational harm, or political sensitivity, including to any government official, public figure, or foreign dignitary."

First woman accuses Trump of sexual abuse

According to the newly released files, the FBI internally circulated Epstein-related allegations that mention Trump in late July and early August 2025. The list, collected from the FBI's National Threat Operations Center, included numerous salacious allegations. Agents marked most of the accusations as unverifiable or not credible.

But one lead was sent to the FBI's Washington office with the purpose of setting up an interview with the accuser. The lead was included in an internal PowerPoint slide deck detailing "prominent names" in the Epstein and Maxwell investigations last fall.

The woman who directly named Trump in her abuse allegation claimed that around 1983, when she was around 13 years old, Epstein introduced her to Trump, "who subsequently forced her head down to his exposed penis which she subsequently bit. In response, Trump punched her in the head and kicked her out."

Out of more than 3 million pages of files released by the Justice Department in recent months, this specific allegation against Trump appears only in copies of the FBI list of claims and the DOJ slideshow.

But a review of FBI case file logs and discovery documents turned over to Maxwell and her attorneys in the criminal case against her point to one place the claim could have come from — and how serious investigators took it.

The FBI interviewed this Trump and Epstein accuser four times. That is according to an FBI "Serial Report" and a list of Non-Testifying Witness Material in the Maxwell case that were also released under the Epstein Files Transparency Act.

Only the first interview, conducted July 24, 2019, is in the public database. That interview does not mention Trump.

Of 15 documents listed in a log of the Maxwell discovery material for this first accuser, only seven are in the Epstein files database. Those missing also include notes that accompany three of the interviews. The discrepancy in the file for the Trump accuser was first reported by independent journalist Roger Sollenberger.

According to NPR's review of three different sets of serial numbers stamped onto the files, there appear to be 53 pages of interview documents and notes missing from the public Epstein database.

In the first interview document, the woman discussed ways Epstein abused her as a girl and, in identifying him to investigators, showed a cropped photo of the disgraced financier. Her attorney said it was cropped because she "was concerned about implicating additional individuals, and specifically any that were well known, due to fear of retaliation."

The FBI agents noted it was a "widely distributed photograph" of Epstein with Trump.

A woman whose biographical details and description of Epstein's abuse found in the FBI interview also line up with details from a victim lawsuit. In the December 2019 filing, "Jane Doe 4" does not mention Trump, and the woman voluntarily dismissed her claims against Epstein's estate in December 2021.

Attorneys for this accuser declined to comment.

Elsewhere in the released Epstein files, someone in the FBI wrote on July 22, 2025, before the list and slide presentation were compiled, that Trump's name was in the larger case files and that "one identified victim claimed abuse by Trump but ultimately refused to cooperate."

Second accuser says she met Trump at Mar-a-Lago

The other woman whose mention of Trump made the DOJ's presentation appears in Maxwell discovery files released last month in what's known as a Testifying Witness 3500 material list.

In the first interview of six with the FBI conducted between September 2019 and September 2021, the second woman detailed how Epstein and Maxwell's abuse began while she was around 13 years old and attending the Interlochen Center for the Arts and described how, at one point, Epstein took her to Trump's Mar-a-Lago Club to meet him.

"EPSTEIN told TRUMP, 'This is a good one, huh,'" the interview report reads.

In a 2020 lawsuit against Epstein's estate and Maxwell, the second woman added that both men chuckled and she "felt uncomfortable, but, at the time, was too young to understand why."

That interview was removed from the DOJ's public files some time after initial publication on Jan. 30 and was republished Feb. 19, according to document metadata.

The Justice Department told NPR the only reason any file has been temporarily removed is that it had been flagged by a victim or their counsel for additional review.

Multiple FBI interviews with other people refer to the second woman's meeting with Trump while she was a minor and being abused by Epstein. One interview with a fleeting mention of Trump was removed from the public database and subsequently restored last week, while another interview with the woman's mother is still offline. After publication, the Justice Department said, the file required additional redactions and will be reposted soon.

In that conversation, the mother recalled hearing that "a prince and DONALD TRUMP visited EPSTEIN's house," which made her "think that if they are there then how could EPSTEIN be a criminal," according to NPR's copy of the file that was first published.

The possible omission of files that mention these women's particular allegations against the president come as the Justice Department has warned about other documents it has published in full that include what it calls "untrue and sensationalist claims" about Trump.

At the same time, the Justice Department has removed and reuploaded thousands of pages in recent weeks to fix improperly redacted victim names. That includes documents related to the allegations from these two women, who separately say they were around 13 years old when Epstein first abused them.

Robert Glassman, who represents the woman who testified against Maxwell, sharply criticized the Justice Department's handling of the Epstein files.

"This whole thing is ridiculous," he told NPR. "The DOJ was ordered to release information to the public to be transparent about Epstein and Maxwell's criminal enterprise network. Instead, they released the names of courageous victims who have fought hard for decades to remain anonymous and out of the limelight. Whether the disclosures were inadvertent or not—they had one job to do here and they didn't do it."

A DOJ spokesperson told NPR that the department is working "around the clock" to address concerns from victims and handle additional redactions of personally identifiable information that have been flagged.

"In view of the Congressional deadline, all reasonable efforts have been made to review and redact personal information pertaining to victims, other private individuals, and protect sensitive materials from disclosure," the statement reads. "That said, because of the volume of information involved, this website may nevertheless contain information that inadvertently includes non-public personally identifiable information or other sensitive content, to include matters of a sexual nature."

NPR's Saige Miller and Ryan Lucas contributed reporting.