Monday, March 31, 2025

A Perfect Storm Is Brewing

Trump is killing jobs. Trump is killing your retirement. Trump is raising prices. Trump is causing inflation. Trump is causing a recession. Trump is causing a trade war. Trump is hurting kids. Trump is hurting seniors. Trump is hurting veterans. What is it about those messages that cuts politically? What is it about them that spells trouble ahead? Why do those messages matter going in to 2026? Because they’re the truth.

Meanwhile, out in the warming Spring waters of the political Atlantic, we’re seeing the early swirl of a perfect storm: a potential Category 5 hurricane forming. Nothing is certain yet; maybe it shifts north or south, fizzles out, or blows inland over empty territory. But storms this big have a way of finding land, and the signs are all there. Imagine an election where the damaging ripple effects of Trump’s spectacularly ill-conceived trade war have six full months to radiate through the economy—hitting the very voters Trump once claimed to champion: rural farmers, non-college whites, and blue-collar workers. Watch those golden promises melt into a haze of retaliatory tariffs and mass layoffs. Imagine an election where the DOGE cuts Social Security, Medicare, and veteran programs and benefit cuts—all accompanied by brazen breakages of the systems that deliver real care—send seniors to the streets in anger. The Third Rail is very real, and it can be fatal for any politician who grabs it. Imagine an election where Democrats almost ignore Trump in their attack ads and instead substitute Elon Musk. You should. He’s less popular, and doesn’t invoke the MAGA/GOP immune response to any critique of Trump. Imagine an election where Trump’s random obsessions—Greenland, Canada, the Kennedy Center—stop being nod-and-wink Republicans inside jokes about “owning the libs” in the D.C. bubble and become concrete anchors, dragging down every Republican clinging to his coattails. Imagine trying to defend invading Greenland when Michigan and Wisconsin are in an economic collapse because of auto tariffs. Imagine an election where Trump’s mumblecore ramblings and perpetual retcons—excused by the compliant Washington press corps for years—get harder and harder to spin. Remember the “Did the White House cover for Joe Biden’s decline?” obsession of a few weeks ago? That’s fluff compared to ignoring Donald Trump’s daily bouts of dimwit glossolalia. Imagine an election where America’s institutions, long asleep under normalcy bias, finally snap awake. We’ve seen some small and limited pushback against Team Trump’s ceaseless demands for total compliance. Some of the law firms he’s extorted and punished who complied — Paul, Weiss and Skadden — have poisoned their brands. The ones standing up — Wilmer Hale, Jenner and Block, Perkins Coie — will in the end of this be seen as fierce fighters for their clients and the country. Imagine an election where Trump’s casual betrayals of Wall Street and Silicon Valley—after they showered him with billions—start to sting. The “number go up” dream gets deflated by his random policy whiplash. Trump just floated that he’s going to screw them on the promised Musk-Zuck-Bezos-Blackrock tax cut. The number of Wall Street donors who’ve told me, “Yeah, I hate him, but for my firm I need support him because of the tax cut and economic growth.” Imagine an election where Democrats pivot to one simple message: “This is madness. He’s hurting you. We’ll stop it.” Imagine an election where Democrats recruit candidates who fit their districts, even if they’re more conservative than the coastal donor class would prefer. We saw it work in 2018 with Nancy Pelosi’s DCCC netting 41 seats by letting local candidates be themselves. Imagine an election where the anti-Trump forces beat the MAGA crew at their own attention-economy game—outmaneuvering Fox News, Elon’s troll-laden social media platform, and every right-wing echo chamber. It’s not easy, but the pieces are sliding into place. I am not, famously, a ray of sunshine. I have seen the Democrats snatch more defeats from the jaw of more victories than I can possibly count. This political zombie apocalypse has taught me to plan for the worst. (“How much ammo do you need?” “How much is there?”) |

Sunday, March 30, 2025

Thursday, March 27, 2025

Wednesday, March 26, 2025

LINKS TO RELATED SITES

- My Personal Website

- HAT Speaker Website

- My INC. Blog Posts

- My THREADS profile

- My Wikipedia Page

- My LinkedIn Page

- My Facebook Page

- My X/Twitter Page

- My Instagram Page

- My ABOUT.ME page

- G2T3V, LLC Site

- G2T3V page on LinkedIn

- G2T3V, LLC Facebook Page

- My Channel on YOUTUBE

- My Videos on VIMEO

- My Boards on Pinterest

- My Site on Mastodon

- My Site on Substack

- My Site on Post

LINKS TO RELATED BUSINESSES

- 1871 - Where Digital Startups Get Their Start

- AskWhai

- Baloonr

- BCV Social

- ConceptDrop (Now Nexus AI)

- Cubii

- Dumbstruck

- Gather Voices

- Genivity

- Georama (now QualSights)

- GetSet

- HighTower Advisors

- Holberg Financial

- Indiegogo

- Keeeb

- Kitchfix

- KnowledgeHound

- Landscape Hub

- Lisa App

- Magic Cube

- MagicTags/THYNG

- Mile Auto

- Packback Books

- Peanut Butter

- Philo Broadcasting

- Popular Pays

- Selfie

- SnapSheet

- SomruS

- SPOTHERO

- SquareOffs

- Tempesta Media

- THYNG

- Tock

- Upshow

- Vehcon

- Xaptum

Total Pageviews

GOOGLE ANALYTICS

Blog Archive

-

▼

2025

(1050)

-

▼

March

(47)

- THE ORANGE EXTORTIONIST

- IT'S FOR YOUR OWN GOOD

- THE ORANGE MONSTER

- A Perfect Storm Is Brewing

- MIKE JOHNSON NEEDS TO GET OUT OF THE CLOSET AND CO...

- MORONS ACROSS THE BOARD AND NOW CRIMINALS AS WELL

- HOWARD TULLMAN JOINS LISA DENT ON WGN RADIO TO DIS...

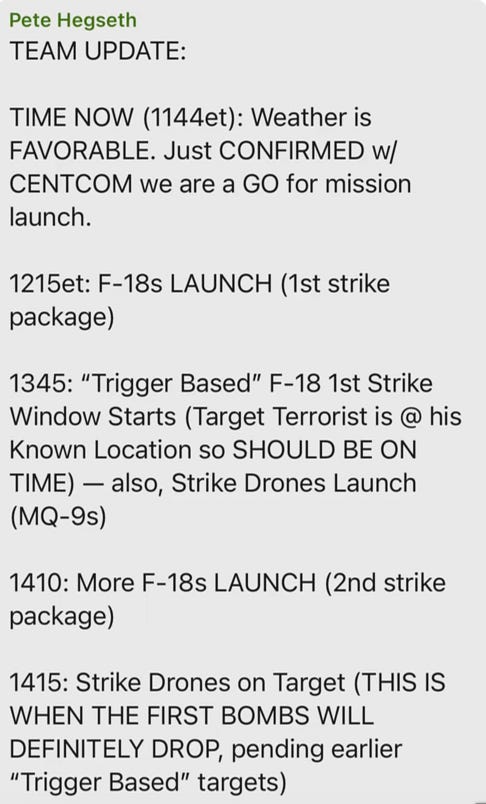

- DRUNK DEFENSE SECRETARY LEAKS WAR PLANS

- Trump Text Fiasco Worsens as Brutal Details Wreck ...

- Trump’s Angry Rant over Hegseth Fiasco Makes Scand...

- NEW INC. MAGAZINE COLUMN FROM HOWARD TULLMAN

- The Supreme Court Must Rescue Itself From Its Own ...

- Boasberg Will Not Relent

- PUTIN'S PUSSY

- Dept of Re-Education

- Howard Tullman Joins Lisa Dent on WGN Radio to Dis...

- Michael Gerson

- Joyce Vance

- WE WERE ALL WARNED

- WAKE UP!

- Chris Murphy

- Rahm Emanuel Is Gearing Up to Run for President

- NEW INC. MAGAZINE COLUMN FROM HOWARD TULLMAN

- DANA MILBANK - AD HOC

- Maga Morons - Musk Minions

- TRUMP'S TRASH

- TRUMP'S RECESSION IS ON ITS WAY

- TRUMP AND TESLA IN THE TOILET

- HOWARD TULLMAN JOINS LISA DENT ON WGN RADIO TO DIS...

- Trump’s Crazed Midnight Tirade Over Musk’s Unpopul...

- TRUMP SLUMP

- NEW INC. MAGAZINE COLUMN FROM HOWARD TULLMAN

- Electing an ignorant, narcissist president and sp...

- A Russian asset: Trump’s policy behavior confirms ...

- Will Harvard Bend or Break?

- WHO WILL STOP THE INSANITY? TRUMP IS CLEARLY NUTS ...

- VANCE

- FACTS TO SHARE WITH YOUR FRIENDS

- DANA MILBANK

- SPINELESS MAGAt SCUM

- HOWARD TULLMAN JOINS LISA DENT ON WGN RADIO TO DIS...

- ASHAMED OF TRUMP

- PUTIN'S PUSSY

- MORE SICK MESS FROM PRESIDENT MUSK

- NEW INC. MAGAZINE COLUMN FROM HOWARD TULLMAN

- CRAZY KENNEDY MEASLES

-

▼

March

(47)