The

Moment That Should Have Changed Everything

OCT 07, 20205:50 AM

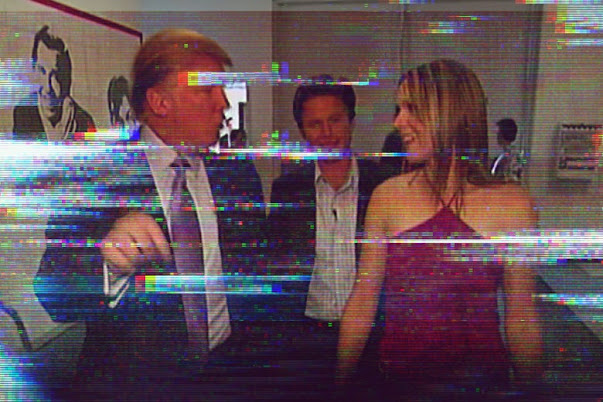

Four years ago this week, news broke that the Republican nominee for

president, Donald J. Trump, had been caught on tape talking with Access

Hollywood host Billy Bush about his habit of sexually assaulting

women. In that 2005 conversation, the then-Apprentice star bragged

about grabbing women “by the pussy,” kissing women before they can stop him,

and “moving on” a married woman “like a bitch.” Trump already had image

problems that didn’t square with either party’s idea of presidential behavior,

but the tape offered testimony (from the offender’s own mouth) that he was more

than just a boor: He was a predator, and he’d been caught confessing. The case

against him seemed complete. The “businessman” whose casinos declared

bankruptcy and whose “university” was beset with fraud allegations had

established his Republican bona fides on birtherism and campaigned on building

a wall and imprisoning his opponent. Now it turned out he was proud of

assaulting women. Everyone could hear the truth for themselves. And nearly

everyone with a platform who did—it can be hard to remember that this was

true—thought this would be the ignominious end of an ugly reality TV candidacy.

It seemed like the defining, karma-laden October surprise of the election.

Misogyny isn’t rare—Hillary Clinton’s campaign made that crystal clear—but no

one really thought a broad swath of the American public would find sexual

assault not just electable but charming. That moment was not so different from

the peculiar and pivotal moment we’re living through in October of 2020, with

the president infected with a deadly virus whose seriousness he has downplayed

for months. Only in 2016, the certainty that it was over for Trump when

the Access Hollywood tape dropped was even more universal. The

day after the tape was released, Mike Pence condemned what he had heard. Trump

even gave something that passed for an apology. It would be the final

concession he would make on the record to societal expectations of good

behavior.

Then the spin began: We heard the “locker-room talk”

defense—which effectively turned the world into a metaphorical “locker room”

where men could be indulgently absolved of anything misogynistic they said,

provided they weren’t addressing women. It was an ugly exercise in special

pleading, but Fox News beat the drum and we know how it ended: An event that

everyone at the time saw as manifestly disqualifying got repackaged as no big

deal, and also somehow “fake news.” It even produced a handy shorthand about

how Trump is a victim persecuted or held to impossible standards. We now know

what that “victim” of the terrible media was up to: Trump spent those weeks in

October trying to keep Stormy Daniels quiet about the affair they’d had while

Melania was home with their newborn son, Barron.

In other words, it was an inflection point that didn’t come

to pass, a moment when everything should have changed and didn’t. The Access

Hollywood tape proved that either Republicans no longer reacted to

scandal, one of their biggest political tools, or they had never been serious

about the “family values” version of decency they’d spent decades

professing—and saw a woman’s right to not be sexually assaulted as negotiable.

(A year later, Steve Bannon would describe the moment as a “litmus test” for

who Trump’s true supporters were.) Just a few days after the tape broke, and

after Trump denied the veracity of its contents at a presidential debate,

several women came forward to describe Trump doing variations of what Trump

said he’d done to them—confirming that this wasn’t idle “locker talk” but an

accurate description of his conduct. The Trump campaign called them

opportunists and liars, and many Republicans followed suit. For all that the

GOP claims to admire Melania Trump, by the time news broke in January 2018 that

Trump had cheated on her with Stormy Daniels and Karen McDougal, Republicans

were committed to a moral program that implicitly condoned the president

groping women, sexually assaulting them, cheating on his wife, and paying hush

money to cover it up. They’d already ignored more than a dozen specific

allegations of sexual assault; by continuing to support Trump, the Republican

position became not just politically expedient—it became the party platform.

Anything Trump had done to women would not be enough for them to abandon him.

Did this debase the office of the president? Certainly. More

importantly, perhaps, it clarified that the party in power had consciously

decided not to see women as equal citizens under the law, but it had also decided

that women were no longer worth protecting. The second bit matters: Inequality

for women is hardly new, but the patriarchal compromise has long been that you

sacrifice equality in exchange for masculine protection. In dispensing with

even lip service toward that principle, Republicans made the fine print of that

bargain—and their specific version of the offer—clear to more than half the

country: You get political subjugation, and we’ll side against

you with your assailant if you’re ever harassed or attacked.

Women shoulder a lot. Their rights have been deprioritized

by both political parties for decades. They are used to slights and oversights.

But when a society makes its indifference to victims this apparent—when it

normalizes and excuses predators and then worships them—the entire intolerable

apparatus snaps into focus: How insult after insult is expected to be absorbed.

How assault gets metabolized and dissected into questions of intent rather than

effect. How the pursuer is sympathized with while the pursued party is

characterized as ungenerous or unforgiving or mean. How the predator isn’t just

unpunished or tolerated, but lionized.

The Me Too movement emerged in part as a lunge toward

accountability in the year after the Access Hollywood tape—and

after witnessing how the many Trump accusers who came forward were treated.

That the movement would suffer a backlash was apparent from the moment it

began. Correcting a mille-feuille of misogynistic habits was never going to

happen in one year or even three, and the stakes were sky-high. Some very rich

men lost their jobs or had to leave the public eye for a while. People do not

like that. There’s an underexamined cost to enforcing social

norms that prioritize equality over sexist defaults. Let’s face it: It’s awful

when a beloved author or actor or icon turns out to have been a sexual

predator, and not just because of the victim. Repeatedly having to choose

between famous and beloved men and their lesser known accusers starts to feel

like a lose-lose proposition. “Canceling” was read by some as a laughably mild

response to a sometimes criminal offense, and by others as an intolerable

extralegal intervention.

It was clear at the time just how much Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation saga in Trump’s second year, with Me Too still powerful but wobbling, was a part of the greater Trump cycle—how, as Trump’s pick, despite obvious and disqualifying defects, the judge became an avatar for a fight that the president and his party believed they had already won. Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearings would radicalize people on both sides of the question. Many Republicans found it terrifying to see a man questioned over assaults he may have committed as a teenager and retrenched to a “boys will be boys” posture that implicitly condones the assault of teenage girls so that teenage boys can make their sexual mistakes without negatively affecting their own futures. Democrats—women especially—were horrified by how Republicans treated Christine Blasey Ford and by how Kavanaugh conducted himself, raging at senators and at the American people, vowing revenge because someone dared to question his conduct. But Kavanaugh had learned Trump’s lesson: He first presented himself to the American people as a mild-mannered, kindly churchgoer. By the time of his hearing, he’d revised his performance to a Trumpian model that understands shouting as powerful and male anger, no matter how hysterical, red-faced, and unglued, as honest.

It’s a sign of how far down an ugly road we’ve traveled

that, when a bona fide rape accusation against Donald Trump emerged last year,

it sank like a stone. This was probably in part a demoralized learned

behavior—we knew by now that no accusations of this kind would dent his

support. It didn’t help that the Me Too movement was in full backlash; the fact

that Julie Swetnick, one of Kavanaugh’s three accusers, turned out to be less

than reliable (as would Tara Reade, Joe Biden’s accuser) scrambled an

overwhelmed public’s ability to meaningfully respond to allegations of sexual

misconduct. E. Jean Carroll’s description of Donald Trump attacking her in a

dressing room was extraordinary in that it understood this landscape: It

perfectly foresaw the conditions of its nonreception. Carroll grasped that

Trump was, politically speaking, scandal-proof. That didn’t change what had

happened to her, but it could, theoretically, free her up to tell her story a

different way. So she did. Carroll broke with the conventions and laid out her

narrative: rather than smash herself against public indifference toward the

president assaulting people because it clearly wouldn’t “sink him,” her account of being attacked situates him

among many such assailants in her life. It forefronts her personhood,

complete with her foibles, charms, defects, resilience, and whimsical

anecdotes. It subordinates Trump to a larger story about the forces that shaped

her. In the book from which that essay is excerpted, she quite originally

acknowledges her own occasional awfulness. The list of Hideous

Men she uses to structure the book comes to include her as a “Hideous Man” too.

And now, in yet another oft-buried headline, Carroll is

suing Trump for defamation and requesting that he submit a DNA sample to

compare with the dress she wore on the day of the alleged attack. While

Attorney General William Barr corruptly forces the Department of Justice to

represent Trump for a crime he allegedly committed long before he was

president, Carroll has spent the past few months interviewing the women Donald

Trump allegedly groped and harassed and publishing the conversations in the Atlantic. It’s a fascinating series both

for its candor and for how firmly it insists on the alleged victims’ right to

commiserate and talk about their experiences in any way at all. One detects in

these conversations a certain freedom that comes from not “mattering.”

So it’s worth pausing to reflect on how we got here. Trump

is running for reelection, and the 26 women who have accused him of sexual

misconduct are so far from being an issue in the campaign for president of the

United States that I had to Google the number to double-check. Bill Cosby was

taken down by the drip-drip-drip of additional accusations because his brand

was respectable. Trump has so blatantly annihilated any expectation that he

might behave decently that no one even bothers anymore. And so the man who

normalized sexual assault and made it a part of the power of his office is now

poised to replace a champion of women’s rights with his third Supreme Court

justice, a woman who has expressed her openness to eliminating gay marriage and

abolishing reproductive freedom. It’s not where I thought we’d be when

the Access Hollywood tape dropped four years ago. Not even I

thought misogyny could achieve this much.