Yeelen Gallery director Karla Ferguson deployed something special at this year's Art Basel showcase: an exhibition exclusively exploring identities of black women.

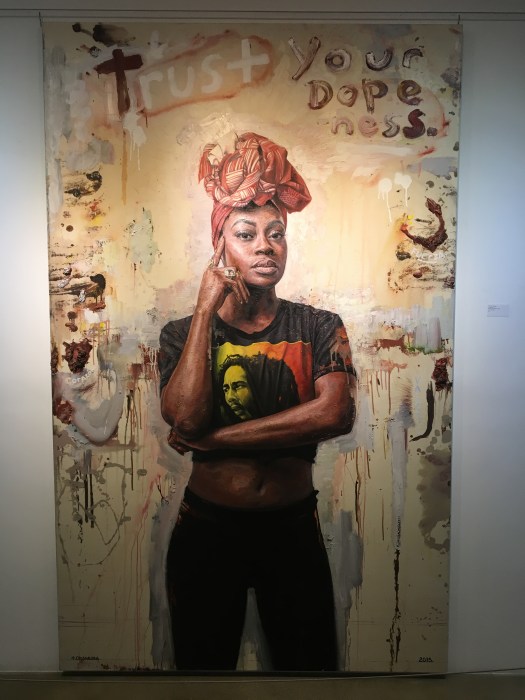

The exhibit, "what's INSIDE HER never dies…a Black Woman's Legacy," features portraits, drawings and larger-than-life paintings depicting women of color in various stages of the human experience. The perspectives range from everyday women to a series of familiar mothers of children who have been killed by police in the United States.

"The vision behind the exhibition was to show the beauty of women of color, not just physically or aesthetically, but mentally too, as well as to show their femininity, fragility and strength," Ferguson told NBCBLK.

Images from the exhibition first appeared in the latest edition of Poets & Artists Magazine, curated by Ferguson, and made their physical debut at the Yeelen Gallery in Miami's Little Haiti neighborhood during Art Basel in December. The show will be on display through February 28, 2016.

NBCBLK contributor Craig Stanley visited the gallery on opening night and caught up with the curator and artists to learn more about their powerful contributions.

Karla Ferguson, Curator & Director, Yeelen Gallery

How would you describe the connection between the pieces of this exhibition?

The common thread is identity and humanity. Each work adds to character of a Black Woman in that it develops a complex personality based on various life experiences, maturity level, stages of grief, pain and joy.

It challenges the viewer to see the subject as multidimensional, and allows me to contribute to the education and understanding of what being a black woman in USA is. It removes the cloak of invisibility and beckons the viewer to really see her. It also reminds them that they cannot destroy her essence because what's inside her will always be passed on.

What inspired you to choose this subject so showcase at Art Basel?

I try not to censor myself, and I find that the time we have on this planet as human beings is limited. I truly believe that if I have a voice and I understand a lot of the ways of the world- in my short time, that it's up to me, and based on my ancestors and the struggles that my people have had, that I need to speak up.

I will no longer be silent when I see injustice and when I see people being treated as second-class citizen in their own country. I have a legal background, and I understand racial profiling at the legal level, and to be targeted in a legal way.

I understand the difficulty there is to change a law with legislation. We don't have the full picture, we don't have the voice of all people participating in a democratic society. And so I find that, with art, of high quality and with strong messages, I believe it's one tool we can use for change.

------------

Sylvia Parker Maier

How did you come to depict mothers who've lost their children to police violence in this way?

I have a series called the currency series where I paint faces as coins, looking at faces as value. I explore the question of, what if in the 'end,' it's not about your monetary currency but your spiritual currency? And what if the more you value yourself, your higher currency is? How can we increase our value through that?

I was commissioned for the show, and asked to do something related to civil rights, in the image of victims, or perhaps a civil rights leader. I'd just come off of a tour of a painting, depicting the moment when Jesus meets his mother in the stations of the cross, and I began to wonder: what's Trayvon Martin's mother feeling? What are the moms feeling?

And being a mother, I wanted to paint the moms. I figured with the black lives matter movement [happening], dealing with value and the coins were appropriate.

What was it like to have these women pose for you?

I knew I'd be needing a lot of tissues, and it was really challenging because of the nature of the subject. I really wanted to serve them, and it was beyond the gallery--it was beyond anything. For me it was really about serving these mothers, serving their children, serving the dead. I wanted to do such a good job for them and bring it to completion. I kept thinking, "they're super women," and the strength in that was really what kept me going.

------

Tim Okamura

Describe your connection to these pieces.

It's something I've gravitated toward over time. As a figurative painter, I became attracted to the idea over time of representing women underrepresented in the history of traditional figurative art.

I look at portraits as a form a story telling, and I feel like these are the stories that haven't been told before, or at least very sparsely. So that become the lane I wanted to stay in, in terms of choosing subjects and stories, and really wanting to create positive imagery and positive messages surrounding these women I think are amazing representations of female strength.

What is your creative process like?

I always like to have part of it planned, and part of it unplanned. I sort of know what I'm doing with the figure generally, and I know what she's going to look like essentially. But I like to have some moments that are more spontaneous, allowing for happy accidents, and for a little bit of the emotion of the moment to come through.

That's what's happening with a lot of the paint technique, and even with some of the collage. It's very spur of the moment, like 'it needs this, it needs that.' I need to respond to how I'm feeling at that time. And that' s a lot of the fun for me: not knowing exactly in which direction things are going to go, but still making something happen that supports the basic idea I had in mind at the beginning.

----------

Jerome Soimaud

What did you want to accomplish with your pieces in this exhibition?

My idea was to bring to the show the spirit and the energy of women who have not yet—or may never, I hope for them— experienced the pain and suffering that the mourning mothers are experiencing for the rest of their life, and I thought it was important to get the two sides of life. You know, the hope, and the resilience. And I think that's also what the mother passes to daughter, that resilience.

Where there any difficulties getting through these series?

Each work is extremely challenging, and that's why I am interested in accomplishing it. For some, it's going to be the hair, to recreate the fluffiness of an afro, or the tiny details of as shaved head. The most challenging, but most important, I think is to give life. Life comes from the size of the eyes. What are the eyes are going to send to the viewer, what kind of energy? All of that comes with very tiny details of lighting, and it's very subtle.

What keeps you going while you're creating these pieces?

Love. Artists are very old kids, and kids function and work with love. When you have kids, they just want to say "I love you'' — that's the value, that's how they speak. I want to put love in my work, for love is the essence of me.