Friday, January 31, 2025

Jim Acosta defined CNN under Trump.

Jim Acosta defined

CNN under Trump. Now he’s gone ‘independent.’

The longtime anchor

signed off with a typically defiant message.

January

31, 2025 at 6:30 a.m. ESTToday at 6:30 a.m. EST

On Tuesday morning, Jim Acosta said goodbye to

his 10 a.m. CNN audience with a familiar message: “Don’t give in to the lies.

Don’t give in to the fear. Hold on to the truth and to hope. … I will not give

in to the lies. I will not give in to the fear.”

That’s a sampling of the anchor-chair defiance that CNN’s

leaders wanted to move to a time slot when much of the United States is asleep.

Prior to his departure, Acosta was offered a

two-hour show from midnight to 2 a.m. Eastern time — one hour longer than his

morning gig and airing from 9 p.m. to 11 p.m. on the West Coast. That offer was

part of a CNN schedule realignment that saw Wolf Blitzer move to a 10

a.m.-to-noon slot, in a partnership with co-host Pamela Brown, along with a

number of other adjustments.

“I think that there was an effort on both sides to make it

work,” said a knowledgeable CNN source, adding that the offer would have

enabled Acosta to dominate late-breaking news events, such as Wednesday

night’s plane crash over

the Potomac River.

Acosta turned down the offer to become CNN’s midnight guy.

President Donald Trump reveled in the goings-on in a Truth Social post, calling Acosta a “sleazebag” and mocking the proposal to

move him to the “Death Valley” of the cable news lineup. Not a great moment for

CNN.

Acosta’s decision prompted a fair bit of commentary that

he’d be a fine fit on

MSNBC. He went, instead, to an outlet with a bit more ideological diversity.

“As you could see earlier today, this was my last day at CNN, and I did want to

jump on Substack Live here for a moment and say, welcome to my new venture.

I’m going independent, at least for now.” He has already racked up 109,000

subscribers.

Planted amid a flurry of headlines from the Trump White

House, Acosta’s move was a moment unto itself, if only because it punctuated a

sharp break from how CNN approached the first Trump presidential term. It’s all

about tone: CNN reacted again and again with chyronic outrage to the first-term

initiatives and antics of Trump, with Acosta a prominent representative. He

antagonized Trump at news conferences, sparred with the president’s press

secretaries at briefings and saw his White House press pass revoked in 2018

after he refused to surrender the microphone during a Trump news conference.

CNN rallied around him and filed suit to have it reinstated.

“Thanks to everybody for their support,” Acosta tweeted at the time. “Let’s get back to work.”

Acosta forged his public news persona when CNN was under

the leadership of Jeff Zucker, a zone-flooding sort of news boss who leveraged the chaos of the Trump era for ratings

and buzz. CNN was out front as a target of Trump’s media-bashing and out front

in pushing back. In a memorable August 2018 clash, Acosta asked White House

press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders to declare that the news media assembled

in the briefing room were not the “enemy of the people,” a phrase that had been

used by Trump. She declined the invitation.

CNN has undergone a great deal of management turnover since

those contentious days and is now under the ownership of Warner Bros.

Discovery. Chairman and CEO Mark Thompson, formerly of the New York Times, runs

the organization. As reported by Oliver Darcy of Status, Thompson instructed top network talent before the

inauguration “to be forward-thinking and to avoid pre-judging Trump.” Darcy, a

former CNN reporter, also remarked in a recent podcast that the current management has fostered a “very

different CNN in tone” when it comes to coverage of Trump.

Maybe so, though it’s easy to romanticize the pugilistic

version of CNN under Zucker. Remember, for example, that CNN, amid its zeal

over the first-term Trump, attributed undue credibility to the Steele dossier,

a document claiming all sorts of Trump-Russia collusion that has fallen apart

under the scrutiny that time affords. Pressed to come clean in 2020, CNN did not. Former CNN staffer Chris

Cillizza recently posted a thread on X explaining

that he’d “screwed up” in dismissing Trump’s

pet theory that the coronavirus originated in a Chinese lab.

There’s an editorial lane for CNN as it approaches Trump’s

second term: Investigate the daylights out of Trump’s initiatives; grill his

top lieutenants in prolonged interviews; and report the results to CNN’s

audience. Meanwhile, ditch the editorial froth that piled up in the early Trump

years — a more sober approach that appears to be taking hold among CNN’s

mainstream peers as well. “The philosophy now is to cover this administration

in a tough but fair way based on reporting,” said the CNN source.

CNN on Tuesday issued a cheery press release touting

its digital performance in 2024 and healthy TV ratings in key categories. And

last week, Thompson announced layoffs as

well as a new digital strategy — fueled by a $70 million investment from its

parent company — to capture an audience that is gradually but inexorably

migrating away from linear television to everything else. That makes CNN about

the millionth company in recent decades to pair staff reductions with plans for

digital conquest. Don’t dismiss the company’s prospects, however, considering

that Thompson was a key player in

bringing about the financial recovery of the New York Times from 2012 to 2020.

Thompson’s initiatives will all collide with CNN’s peculiar

audience crisis. No matter how it positions itself vis-à-vis Trump 2.0, the

network’s public image remains rooted in its treatment of first-term Trump —

meaning conservatives would sooner pony up for the DEI Network than for CNN

subscription products. Hold on to hope, as Acosta might say.

WE USED TO HAVE HEROES - NOW WE HAVE LYING SCUMBAGS LIKE TRUMP

“Not surprised. Disgusted.” — Capt. Chesley

“Sully” Sullenberger¹, on Donald Trump’s

attempt to blame the DCA tragedy on DEI.

Sully is the pilot who safely landed a

passenger plane in the Hudson River in

2009, in what became known as the

“Miracle on the Hudson.” He made the

comment on Lawrence O’Donnell’s show

after what seemed an heroic effort not to

He Is the Same Awful Man

Thursday, January 30, 2025

Trump’s Chaos Strategy Is Already Blowing Up in His Face

Trump’s Chaos Strategy

Is Already Blowing Up in His Face

An interview with New Republic writer

Timothy Noah, who argues that Trump’s funding-freeze fiasco shows that he’s a

“weak president” whose vaunted “chaos strategy” is already running into

trouble.

r/GGreg Sargent: This

is The Daily Blast from The New Republic, produced and

presented by the DSR network. I’m your host, Greg Sargent.

On Wednesday, Donald Trump’s administration rescinded the memo that instituted his disastrous

spending freeze in what looks like a surrender in the face of a national

outcry. Soon after, Trump went before the cameras and pushed

a bizarre lie about $50 million in U.S. taxpayer money supposedly

being spent on condoms for Hamas in Gaza. This kind of thing is often described

as a “flooding the zone” strategy, in which Trump throws so many lies and

abuses of power at us that we can’t keep up. Checkmate libs, Trump wins! But

what if this chaos strategy actually isn’t all that clever after all? What if

it’s more likely to backfire? Today, we’re talking about this with The New

Republic’s Timothy Noah, author of a good

new piece arguing that Trump’s chaos strategy is all about creating a

pretext to consolidate power. Tim, thanks for coming back on.

Timothy Noah: Thanks for having me.

Sargent: Let’s start with Trump’s lie about condoms.

Here’s what Trump said on Wednesday about the process of rooting out waste,

fraud, and abuse that his government is supposedly undertaking now.

Donald Trump (audio voiceover): In that process, we

identified and stopped $50 million being sent to Gaza to buy condoms for Hamas.

Fifty million. And you know what’s happened to them? They’ve used them as a

method of making bombs. How about that?

Sargent: Tim, MAGA is pushing this one hard. Press

secretary Karoline Leavitt made this claim from the White House press podium; a

State Department spokesperson also pushed it. The Washington Post’s Glenn

Kessler looked at it and found that it’s made up. He asked

Leavitt and the State Department spokes for documentation, and they had

nothing. They’re really struggling to prove that their hunt for waste and abuse

is yielding anything at all. What are they trying to do with this?

Noah: Yeah, it is entirely made up. Trump says things

because he likes the way they sound. I do put forward this theory in my piece

that the way authoritarians consolidate power is to manufacture crises. And

that is clearly what the Trump team is doing. But I should add an

important caveat, which is that chaos comes naturally to Donald Trump. He is a

mentally disabled president of the United States—I think that’s the only way

you can describe it. He has a narcissistic personality disorder that’s well documented,

and he has had some decline in cognition that’s also been documented and

observed by a number of medical professionals and others.

So you have this crazy guy who is president of the U.S.

saying all sorts of things, and it creates mayhem. This is being channeled by

his aides to, as I say, manufacture crisis and manufacture chaos, but it

isn’t working.

Sargent: At least not yet, that’s for sure. The

administration has now rescinded the memo instilling that massive spending

freeze, which had caused chaos and confusion and threatened to have a huge

impact on all kinds of government programs. It’s a little unclear what happened

here. They seem to be still trying to pause some spending but this is

clearly a surrender, I think. You wrote in your piece that Trump probably

thinks turning off all that federal spending was also beneficial to his larger

strategy of consolidating power. How would that work exactly?

Noah: I don’t believe that either Donald Trump nor

Russell Vought, who is Trump’s yet unconfirmed nominee to run the Office of

Management and Budget, who the White House more or less confirmed has been

running this operation. I don’t think either one of them really understands

what they were talking about in this memo. It concerns something called federal

financial assistance. What is federal financial assistance as opposed to other

kinds of spending? This is outlined in a 1977 law that doesn’t make it hugely

clear.

What we know is that procurement of an object like an

aircraft carrier is not federal financial assistance. However, the purchase of

services is sometimes federal financial assistance, and sometimes not. As a

consequence, you had every agency in the federal government switching off every

switch it could because nobody really knows which falls into which

category. It was utter mayhem.

Sargent: Not only that but it’s clearly illegal. I want

to read a line from your piece, “No president in history, not even Trump in his

first term, ever logged so many illegal actions in so short a time.” So we’ve

got the purge of inspectors general, which was likely illegal designed to make

it a whole lot easier to be really profoundly corrupt at the

agencies. We’ve got the threat to prosecute state officials who refuse to

implement Trump’s mass deportations; that was clearly legally ungrounded. And

now this effort to usurp congressional power and turn off federal spending that

Trump doesn’t like—clearly illegal. I really do think we haven’t seen an effort

to consolidate power quite like this one, have we, Tim? Beyond the whole

question of what the role of chaos is, there’s a mechanical effort to

consolidate power unlike anything we’ve seen.

Noah: Right. And there’s even more impeachable offenses

that you didn’t mention. You mentioned one or two that I hadn’t mentioned. As I

said in my piece, it’s become kind of a parlor game. How many are there at this

point, nine days in? But it looks like he’s doing more than he really is, and

Trump thrives on the playacting part of being president. He says he’s done

things that he hasn’t done, claims credit for things that he can’t claim credit

for. And you’re seeing that here.

The main purpose, I think, of that OMB memo was to assert

that the president has the power to impound appropriated funds. Trump was

trying to just blunder his way into asserting this power over appropriations

that he doesn’t have. It led immediately to all sorts of lawsuits, entirely

foreseeable, and Trump withdrew. Trump is, I have argued, not a strong

president. He is a weak president. He has authoritarian tendencies,

but he’s weak. He’s mentally weak. He is subject vulnerable to all sorts

of manipulation by his aides. He tries to do all sorts of contradictory things.

He is not competent.

And on the evidence of this particular example, neither are

his enablers. Surely, Vought have understood that this memo was going to

be challenged immediately in court. He ought to have been able to anticipate

that Trump could not tolerate the bad publicity surrounding it so that Trump,

even before there was a court judgment, withdrew the memo. These are all signs

of a weak presidency, but weakness can cause chaos too. And we’re

certainly experiencing a lot of chaos, a lot of fear, and a real degradation

of the ability of government to perform its functions.

Sargent: I want to get at your point about weakness and

failure here. An interesting thing is how this contrasts with Trump/MAGA

propaganda right now. That propaganda is relentlessly pushing the idea that

Trump and his allies are ruthlessly forging ahead with his agenda. You see it

all over Twitter. All of MAGA’s tweeting immense congratulations to

Trump, he’s crushing the libs, he’s doing this, he’s doing that.

Noah: You even saw it pronounced by John Harris in Politico, which I have to

say, I still haven’t gotten over reading that piece. I was deeply troubled by

that piece.

Sargent: And The New York Times had an absurd

piece today, essentially saying Trump has got his opponents on the run with this “flood the zone” strategy. The

amount of credulousness, the portrayal of Trump’s strategy as something savvy

and clever and effective, is just so deeply offensive coming from journalists,

isn’t it?

Noah: Yeah, it’s a transference because it’s hard for

us journalists to keep track of everything Trump is doing. But I guarantee

you it is not hard for the people who are going to be making court challenges

to these individual actions because each action has a different constituency

that is focusing on a particular topic and is at the ready to take Trump to

court when he does something illegal.

Sargent: Exactly. The real story here is that they’re

actually screwing up already. The spending freeze is getting reversed. ICE is

already leaking like crazy about how Trump’s demand for much higher arrest is

going to create major problems. The effort to undo birthright citizenship has

stopped in court. I don’t want to be too optimistic here. They’re going to do a

lot of damage—already are doing a lot of damage. But clearly what we’re seeing

now is that they’re not going to be able to roll over the bureaucracy and our

institutions, as easily as they thought, as easily as John Harris thinks, as

easily as that credulous New York Times piece portrayed, right?

Noah: That’s right. Even in the Republican Senate,

Trump was only barely able to get his defense secretary choice, Pete Hegseth,

through. I don’t believe he’ll be able to get Robert F. Kennedy Jr. through.

His whole decision to nominate Kennedy was really a reflection only of

Trump’s vanity.

One of the less attractive qualities of Trump is that he

deeply appreciates seeing people who previously denounced him come crawling on

their knees to him. And that endears him to such people. And in this case, he

rewarded Robert Kennedy Jr. with this nomination to which Kennedy is manifestly

unqualified for, argued with astonishing forcefulness by Carolyn Kennedy yesterday.

Sargent: And by Democratic senators on the Hill, on

Wednesday, we should point out that a number of Democratic senators absolutely

shredded RFK in the confirmation hearing. Can you tell me why you think he’s

not going to get in?

Noah: Well, the basic arithmetic is you’ve got

somebody who isn’t even a Republican, is up against big pharma on all sorts of

bottom-line issues. Republicans don’t like, in the best of circumstances, going

against the business constituency. And I think Trump’s commitment to RFK

Jr. is a weak one. Vaccination and fluoridation are not issues that Trump

really cares about one way or the other.

Sargent: I certainly hope you’re right about that. I

was thinking that he was probably going to get RFK; after today’s hearing, I’m

really not so sure. Tulsi Gabbard looks to me like she might be a very hard one

for some Republican senators to support as well.

Noah: Right. And with RFK, there is a

be-careful-what-you-wish-for component, which is we don’t know RFK to be

committed to eviscerating Obamacare and whoever Trump nominates in RFK Jr.’s

stead, I think, probably will be committed to doing that. And that’s not going

to be very good news.

Sargent: I want to try to pull all this together. Going

back to that ridiculous joke about condoms and Gaza, what we’re seeing here is

an effort across the board to degrade public life in every way possible. Having

the White House press secretary push that absurdity, having ridiculous legal

rationales for immense power grabs, Trump going out there and demanding of his

ICE agents that they hit arrest quotas as has been reported in The Washington Post, everything

is about taking public life and turning it into a big joke.

Noah: Trump offering to buy out federal employees, give

federal employees buyouts to retire. Where the money would come from is

anybody’s guess.

Sargent: Right. And this idea that Trump is this wizard

who can just throw us off with a magical distraction strategy, again, is

constantly treated with unbelievable credulousness by the press. Let’s

talk about that though. The degradation of public life is a thing that’s

happening.

Noah: It is a very, very ugly and mean moment in

American politics.

Sargent: You wrote about the degradation and the

spreading of meanness in U.S. politics and what that means for your newsletter.

Can you talk about that as well?

Noah: Yes, I have a Substack newsletter called Backbencher that

I use mainly to publicize pieces I write in The New Republic. Today,

I wrote about.... Well, I remember my mother telling me in 1968 after Robert

Kennedy was killed—I was 10 years old and my mother said, I don’t

understand what’s happening to this country. I have compared notes with

other people my age and just about everybody I have asked has said yes, they

had a parent say the same thing to them when they were 10 or 9 or 11.

Nineteen-sixty-eight was a terrible, terrible year. We saw

the assassination of Martin Luther King and of Robert F. Kennedy. Later, we saw

this awful mayhem at the Democratic convention. We saw an endless war in

Vietnam. It was a time that was as dismal as can be imagined. People were

saying, I don’t understand what’s happening to this country. And I

think people felt that way during Trump’s first term. I think they feel it more

powerfully now. And I think more and more people will feel that, many

people who voted for Trump in 2024 will feel that. It’s a sad moment. For those

of us who really believe in this country and believe in its government, it is

devastating to see what is being done in its name.

Sargent: Well, just as happened in 2018, we could see

in 2026 some similar backlash, one that is really all about reasserting decency

in public life and pushing back on the degradation of it, don’t you think?

Noah: Yes, I think that there will be a route, but

that’s a long way off. Even longer term ... I don’t know whether you agree,

this is a little out there, but I think the Republican Party is in the process

of disintegrating. Liz Cheney has said that, and I think she’s dead right.

Conservatives, serious conservatives are going to need to start looking for a

new party to create in its stead because the Republicans have really sold out

on just about every principle and have become—this is not an original thought—a

cult of personality. And that isn’t easily undone.

Sargent: Well, one has to hope that you’re right about

that. I’m not sure about the former piece, the idea that the Republican Party

is disintegrating, but the latter piece that any principled conservative really

should have no choice but to seek some alternative is clearly on. Timothy Noah,

thanks so much for coming on, man. Great to talk to you.

Noah: Thanks for having me, Greg.

Wednesday, January 29, 2025

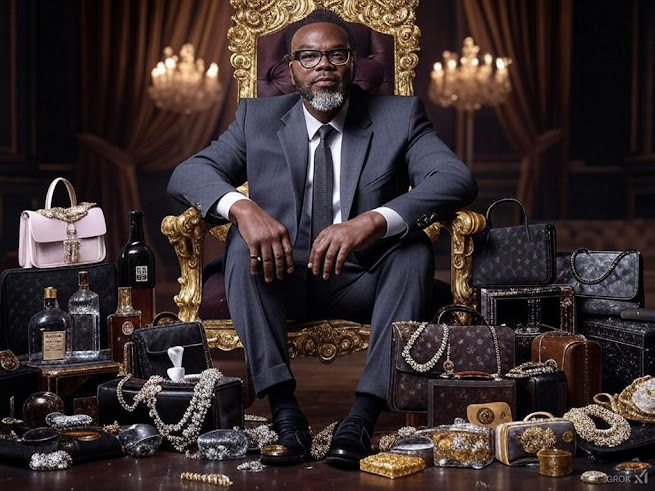

Chicago mayor's office accepted luxury gifts without properly reporting them: OIG

Chicago

mayor's office accepted luxury gifts without properly reporting them: OIG

By Will Hager

Published January 29, 2025 10:10am CST

Chicago mayor's office accepted luxury gifts without properly reporting

them: OIG

The Chicago Mayor's Office accepted gifts ranging from

designer handbags to jewelry on behalf of the City without publicly reporting

them, according to a new report from the Office of Inspector General.

The Brief

·

·

The Chicago Mayor's Office

failed to publicly report gifts, including designer handbags and jewelry,

accepted on behalf of the City, violating transparency guidelines, according to

a report from the Office of Inspector General (OIG).

·

·

When the OIG attempted to

access the gift log, officials were denied and directed to file a Freedom of

Information Act (FOIA) request, which was also ignored.

·

·

The OIG is now urging the

Mayor’s Office to follow public reporting rules and allow inspections of the

Gift Room to restore public trust.

CHICAGO - The Chicago Mayor's Office accepted gifts ranging from designer handbags

to jewelry on behalf of the City without publicly reporting them, according to

a new report from the Office of Inspector General (OIG).

The OIG said gifts accepted on behalf of the City should be reported to

the Board of Ethics and the city comptroller and those reports are required to

be made publicly available. Under an unwritten agreement dating back to the

late 1980s, gifts accepted by the Mayor's Office were instead logged in a book

that would be available for public viewing on the fifth floor of City Hall,

according to the OIG.

The backstory:

The OIG visited City Hall undercover and requested to see the logbook.

The Mayor's Office denied the request and directed OIG officials to file a

Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request.

Inspector general officials said they filed a FOIA request in a

"covert capacity" and the Mayor's Office failed to respond in a

timely manner, reflecting a denial of the request.

The OIG then sent an official document request to the Mayor's Office for

the logbook and received a spreadsheet detailing 380 gifts accepted by the

Mayor's Office "on behalf of the city" between Feb. 2, 2022 and March

20 of last year. Former Mayor Lori Lightfoot's logs included entries for 144

gifts received while Mayor Brandon Johnson's logs contained 236 entries.

Among the gifts given under the Johnson administration were Hugo Boss

cufflinks; Givenchy, Gucci, and Kate Spade handbags; a personalized Mont Blanc

pen; and size 14 men’s shoes, OIG officials said. Some of the gifts were stored

in the gift room and the others were in Mayor Brandon Johnson's personal

office, the inspector said.

The OIG visited the fifth floor to conduct an unannounced inspection of

the Gift Room and was denied access.

"When gifts are changing hands—perhaps literally—in a windowless

room in City Hall, there is no opportunity for oversight and public scrutiny of

the propriety of such gifts, the identities or intentions of the gift-givers,

or what it means for gifts like whiskey, jewelry, handbags, and size 14 men’s

shoes to be accepted ‘on behalf of the City,’" said Deborah Witzburg,

inspector general for the City of Chicago.

Under the Governmental Ethics Ordinance, city officials are generally

prohibited from accepting gifts of value over $50 unless they are

"accepted on behalf of the city."

What's next:

The OIG recommended that the Mayor's Office comply with "generally

applicable rules" for public reporting of gifts accepted on behalf of the

City. They also recommended that the Gift Room be made available for announced

and unannounced inspection by the OIG.

The Mayor's Office responded that it would allow OIG access to the Gift

Room with only "a properly scheduled appointment."

The Chicago Board of Ethics agreed with the OIG's recommendation of

public reporting. The Mayor's Office said it will work with the board to

transition to the new guidance.

Why you should care:

Witzburg said in a statement that the lack of transparency from the

Mayor's Office erodes public trust.

"It is perhaps more important than ever that Chicagoans can trust

their City government, and for decades we have given people no reason at all to

trust what goes on in the dark," Witzburg said. "These gifts are, by

definition, City property; if they are squirreled away and hidden from view,

people are only left to assume the worst about how they are being handled. If

we do not govern responsibly on the small things, we cannot ask people to trust

the government on the big ones."

FOX 32 has reached out to the Mayor's Office for a statement.