Monday, August 31, 2020

Friends

Bill Gates: Of all the things I’ve learned from Warren, the most important thing might be what friendship is all about. As Warren himself put it a few years ago when we spoke with some college students,

“You will move in the direction of the people that you associate with. So it’s important to associate with people that are better than yourself. The friends you have will form you as you go through life. Make some good friends, keep them for the rest of your life, but have them be people that you admire as well as like.”

Sunday, August 30, 2020

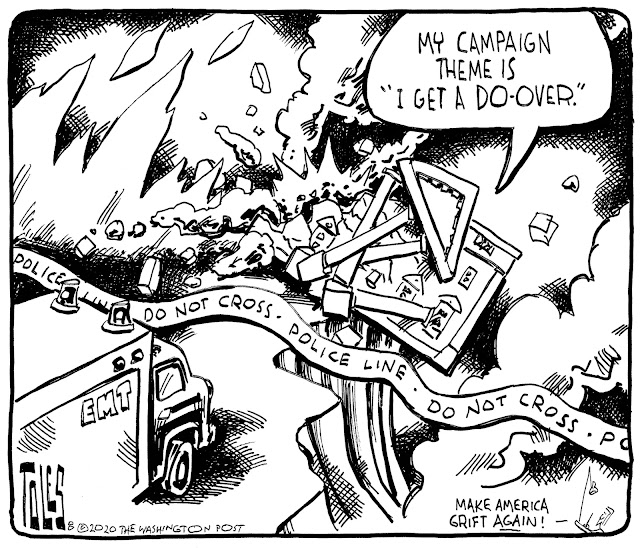

The Democrats Better Wake Up

Violence in Kenosha could be turning point in presidential election

Lawless barbarity is tearing apart cities across the nation.

By Steve Huntley Aug 28, 2020, 3:34pm CDT

The remains of cars burned by protestors the previous night, on Aug. 25, during a demonstration against the shooting of Jacob Blake, are seen on a used-cars lot in Kenosha. Kerem Yucel/Getty

If Donald Trump wins reelection after trailing so badly in the polls, Kenosha may go down in history as a turning point.

The violence there got so bad that Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden finally had to acknowledge what was plain to everyone but hands-over-their-eyes Democrats — lawless barbarity is tearing apart cities across the nation.

Biden condemned “needless violence.” Makes you wonder what kind of violence he thinks is needed.

Kenosha is what happens when law and order retreat, it’s a preview of life in a defund-the-police world.

If police aren’t there to defend lives and property, someone else will eventually step in. In the Wisconsin town, it turned out to be a vigilante type who’s allegedly killed two people. Liberals cry “right wing fanatics.” But that’s more of the Democrat hands-over-their-eyes syndrome.

Don’t think for a minute that the suburban gated enclaves of the wealthy and the upscale condo towers in places like Chicago’s lakeshore neighborhoods aren’t reviewing their security systems and beefing them up. City government moved homeless people, who defecated in the street and harassed area residents, into a hotel in the affluent, overwhelming Democratic Upper West Side of Manhattan, and the locals rose “up in arms,” reported the New York Times.

Americans saw Adam Haner beaten unconscious by a mob in Portland and headed for the gun shop. Firearm background checks by the FBI exploded by 79% in July alone. Nearly 5 million Americans bought a gun for the first time in 2020, reports the National Sports Shooting Foundation — and the year is not over. Guess who’s buying those guns? According to the group’s survey, 58% of all gun sales were by African Americans, and women were 40 percent of first-time gun buyers.

Until Kenosha, even as the fires raged, businesses were plundered and crime skyrocketed, Democrats harped time and time again about “mostly peaceful protests,” insinuating that anyone not falling in line was somehow against First Amendment freedoms. “Mostly peaceful protests” was the evasive response when Trump pointed out the obvious: looting, rioting, arson, beatings and murders were engulfing cities almost exclusively run by Democrats.

Another uncomfortable truth is that the rioting is just the latest manifestation of Democrat-run cities retreating from the “broken windows” theory of policing that made possible the urban renaissance of the last couple of decades. That concept says if you let minor law breaking go unpunished, more serious crime follows. Then came a foolish assertion that the nation is too tough on criminals. The consequences followed.

One of the stark examples was the Sun-Times analysis by Frank Main showing that Chicago’s soaring murder rate came as shockingly high numbers of criminal defendants were let out of jail on electronic-monitoring bracelets. That included more than 1,000 charged with murder, robbery or illegal possession of guns. The stunning revelation that 43 people accused of murder were out on electronic monitoring on one August day came with the even more astonishing disclosure that this was only 40% higher than a year ago.

When Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx dropped all charges against actor Jessie Smollett for his false claim of being a hate crime victim, the message was clear: There’s no rule of law, only the rules Democrat Foxx wants to enforce.

The Trump-hating virus that infects Democrats have them condemning the president for the rioting. Another Chicago example came in Mayor Lori Lightfoot claiming Chicago’s gun violence was the fault of Trump’s failure to enact the kind of gun laws she favors. Pass-the-buck Democrats like Lightfoot, who want the power of government but not the responsibility, will always find a Republican to blame. If Trump is defeated, it will be Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell or a Red State governor or a GOP legislature somewhere.

No one is against peaceful protests. No one wants police brutality to go unpunished. But the overwhelming majority of cops do an impossibly tough job with professionalism and honor.

The Democrats’ retreat from proven police practices set the stage for the riots, chaos and anarchy, reasonably opening them up to the charge that they are soft on crime.

Voters will look at the record and wonder this: If the Democrats are so wrong on the fundamental issue of safe streets, safe neighborhoods and safe communities, how can they be right on Biden’s far left goal to radically transform America with new taxes, intrusive healthcare initiatives and crazy climate change ideas like those have have left California reeling from power outages?

Add to this the Republicans’ successful convention that, among other things, showcased minorities and women not as victims, but as successful achievers and defenders of American ideals, and Trump’s chances start looking better for November.

Steve Huntley is a former editorial page editor and columnist for the Chicago Sun-Times. He can be reached at shuntley.cst@gmail.com.

The five dumbest Republican arguments for Rump

The five dumbest Republican arguments for Trump

Opinion by

Columnist

August 30, 2020 at 9:00 a.m. CDT

None of

Republicans’ commonly deployed arguments for reelecting President Trump are

tethered to reality. The paucity of logic and factual support for their

rationales suggests many on the right, even “respectable” columnists and

elected officials, actually support him for reasons they’re loath to admit,

whether it’s because they share his apocalyptic view of crime encroaching on

the suburbs or are eager to see a country purged of immigrants.

He will

give us law and order: If public safety is the concern, the

unnecessary deaths from covid-19, which might exceed 200,000 by Election

Day, and the anxiety over leaving our homes for fear of joining 6 million

infected Americans surely make Trump’s tenure the most dangerous for ordinary

Americans. Each week, we have been losing twice the number of Americans killed

on Sept. 11.

No

wonder Trump loves to highlight any domestic scene of disorder, mayhem and

looting he can to frighten White Americans, arguing that if law enforcement

“dominates the streets,” we will have public order. This is preposterous. We

cannot go to war with millions of demonstrators. That’s simply impossible, not

to mention morally objectionable. The demands of the protesters, among them

police reform and voting rights legislation are entirely legitimate. But so

long as Trump denies the legitimacy of these concerns and the presence of

systemic racism, we will not have domestic tranquility.

Trump celebrates violence,

encourages police misconduct,

honors Whites indicted for brandishing guns at marchers and tear-gassed peaceful protesters in Lafayette

Square. Senior adviser Kellyanne Conway let on that the

administration believes that the more violence happens in the streets, the better chance Trump has of

being reelected.

Meanwhile,

Trump smears our intelligence community, spinning false conspiracy theories and

adopting Vladimir Putin’s version of the 2016 plot to interfere with our

election. Trump tramples on laws and precedents ranging from the Hatch Act to turning over his tax returns to

the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee upon

request. There is no president in recent memory who has hired and associated

with so many convicted felons. He personally is under investigation by multiple

authorities for potential financial crimes. He is his own crime spree.

He has

vanquished the pandemic: The level of delusion necessary to sustain

the fiction that Trump has handled the pandemic well is unfathomable. We have more deaths due

to the disease than any other country on the planet, many more deaths per capita than many advanced countries and no national

testing-and-tracing program. We remain cloistered at home and children cannot

attend school in person in most places after weeks of shutdowns, largely

because Trumped egged officials into reopening prematurely. He has hawked

dangerous and unproven remedies and pressured government health experts to

weaken or change guidelines to minimize dangers and restrictions on activities.

As he did Thursday night, he gathers large crowds without

masks and social distancing, creating his very own potential

superspreading events.

He has

been great for the economy: Multiple fact-checkers have repeatedly

demonstrated that the economic successes Trump claims were questionable

relative to the economy President Barack Obama built before Trump took office.

This disparity was due in part to tariffs Trump imposed, which amount to a tax

hike for U.S. consumers. If Trump falsely thinks he inherited a rotten economy,

it’s inarguable that he crashed it by attempting to ignore a pandemic. It is

now evident that some jobs lost will not return when — and if — the coronavirus is

vanquished. Hundreds, if not thousands, of businesses have closed. Companies

will not all emerge from bankruptcy. Trump ends his four years with record

unemployment and debt — and without a plan to reduce either.

Joe

Biden is a socialist: Not even the Republicans have the nerve to make that argument.

Instead, they argue that Biden will be tricked or led around by the nose by

forces on the left. This is entirely speculative and ignores Biden’s

decades-long record in office (remember the 1994 crime bill?) and policy

choices during the campaign, among them his opposition to Medicare-for-all.

Moreover, we have yet to see in American politics a situation in which the wing

of a party defeated in the presidential primary magically controls the

executive branch after their rivals from the same party assume office.

Moreover,

if “conservatives” are worried about the expansion of government, then Trump’s

widespread abuse of executive power, meddling in investigations and enforcement

actions to benefit cronies and punish enemies, threats to harm certain

companies (as in his call for a boycott of Goodyear), protectionism

and capitulation to illiberal regimes, as well as the mammoth debt he’s run up,

his indiscriminate use of federal forces against protesters, his misuse of government property and

government employees to serve his personal interests, and

attacks on the courts and free press make Trump the least conservative

president ever (if that word has any meaning anymore).

“Life”:

One can respect those deeply opposed to abortion in evaluating the candidates,

but by the same token, a president who prioritizes the economy over preventing

a pandemic, rips children from the arms of their mothers, refuses to denounce

killings of unarmed Black Americans and willfully declines to protect the lives

of our troops on whose heads Russia

placed bounties is not respectful of human life in any

meaningful sense. Indeed, Trump has turned the party into a vicious death cult

that trivializes the nearly 180,000 deaths caused by covid-19 to date.

When you create superspreader crowds to soothe

your ego, you are endangering human life.

When

one party willfully ignores a pandemic and treats Black lives as expendable, it

loses any moral authority regarding the sanctity of human life. In refusing to

be guided by scientific facts (be it on air and water quality,

climate change or covid-19), Trump puts at risk the health and lives of

millions of people here and around the world. Those who value the essential

worth of every human being should be repulsed by this administration.

Donald Trump’s Greatest Escape

Donald

Trump’s Greatest Escape

His

critics assume this crisis has to take Trump down, whether for the bungled

response or the economic collapse. They’re missing something important: He’s

been training for this moment his entire life.

04/17/2020 05:06 AM EDT

Michael Kruse is a senior staff writer for POLITICO.

His audacity masked his desperation.

It was the spring of 1995. Donald Trump was this close to

finished. He had spent the previous five years constantly, and barely, avoiding

financial ruin and what he worried would be a permanent stain of personal

bankruptcy. In that time, his marriage had collapsed, he himself had incurred

debts of almost a billion dollars, all three of his casinos in Atlantic City

had filed for

bankruptcy, and the best of the three, Trump Plaza, was losing almost $9

million a year.

The aura

of success was gone. Banks wouldn’t anymore lend him the kind of money he

needed. From this crouch, Trump hatched a bold, almost absurd plan: He chose

this moment to take his company public—and sell stock in his casinos. He

created a new company, Trump Hotels & Casino Resorts, Inc., and hoped

to rustle up about $300 million from stock and junk bonds to expand the Plaza,

develop a riverboat casino in Indiana and reduce his personal debt.

Analysts

frowned on the idea. “We are not entirely confident,” one from Standard & Poor’s

warned, “that Mr. Trump will respect the interests and preserve the capital of

equity investors in his properties.” The media was harsher, a columnist

at Newsday portraying Trump as part carny, part con man. “Step

right up, cries the barker with the jaunty derby and twirling cane,” Sydney

Schanberg wrote that April. “Donald Trump has a deal for you.”

A quarter of a century has passed. Trump, of course, is no longer

the cash-strapped operator of gaudy gambling halls on the New Jersey shore but

the president of the United States. Once again, though, he is in dire straits.

Thanks to the coronavirus pandemic and its attendant economic wreckage, the

possibility that he could be reelected has never seemed less certain. The

annals of American history are littered with presidents brought down by their

failures to deal with a national crisis, from Herbert Hoover and the Great

Depression to Lyndon B. Johnson and the Vietnam War to Jimmy Carter and the

Iran hostage affair and the oil shock.

Those presidents, though, had something else in common, too. They

were not Donald Trump.

Because from the early ‘90s, when bankers and lenders in New York

and state regulators in New Jersey could have all but ended him, to his

herky-jerky presidential campaign in 2015 and ’16, to his aberrant, hyperactive

presidency, Trump has built an astonishingly consistent record of surviving

crises, of dodging the comeuppance everyone assumes is coming his way, and then

turning seeming calamity into his next great opportunity—and emerging not just

intact but emboldened.

He dodged the “Access Hollywood” tape fiasco. He evaded the noose

of impeachment over the Ukraine deal. Those might now seem minor compared to

the challenge of trying to get reelected during a worldwide health crisis and a

looming depression—but if one acknowledges that he has been training in some

sense for this sort of a jam for the bulk of his adult existence, then this

nightmarish predicament starts to look less like an uncrackable problem than a

potential capstone accomplishment.

“He’s a magician that way,” said Jennifer Mercieca, a professor at

Texas A&M University and the author of the forthcoming Demagogue

for President: The Rhetorical Genius of Donald Trump. “Other people would

stop and recognize that they were defeated. Or that they should be shamed. He

refuses.”

George Arzt, a Democratic consultant in New York, who’s known

Trump for going on 50 years, likens him to the world’s most noted escape

artist.

“Houdini,” he said.

Few

chapters exhibit this talent of Trump’s better than what happened in 1995.

In the first week of June, Trump stood on the floor of the New York Stock

Exchange and watched over the successful debut of his publicly traded casino

company, the stock symbol his initials—DJT. He got the low end of the price he

wanted, $14 per share, but enough to bring in $140 million, plus an additional

$155 million in 10-year junk bond notes for a total haul of just shy of $300

million.

Trump’s casinos could have been concrete blocks lashed to his

ankles. But at that perilous juncture, he somehow transformed them into a

personal lifeline. From that point until 2009, when Trump stepped down as the

company’s chair, his Trump Hotels & Casino Resorts would pay him $44

million in salary and $82 million overall. The people who invested, who threw

him that lifeline, didn’t do so well: The company lost $1.1 billion over that

time, filing for bankruptcy twice. The stock price would peak at $35.50 in

1996—and ultimately fall to as low as 17 cents a share. “People who believed in

him, that listened to his siren song,” the uber-investor Warren Buffett

would say, “came away losing

well over 90 cents on the dollar. They got back less than a dime.”

That day on Wall Street, though, was nothing short of a

bounce-back win. The government-mandated “quiet period” surrounding an initial

public offering meant Trump couldn’t make any comments. But he didn’t have to.

The look on his face, according to reporting at the time, was all that needed

to be said. He beamed. “He was,” said somebody who was there, “absolutely

ebullient.”

And now, in his scattershot response to this once-in-a-lifetime

crisis—his shoutfests with reporters, his back-and-forth proclamations and

policy impulses, his odd tweets about miracle drugs—Trump’s aghast critics see

a president backed into a corner, desperate and unmanned, in a frantic, final

freefall. But people who’ve watched him for years, who’ve witnessed the

dizzying pivots, the great escapes, the gobsmacking victories in the face of

arguably more unforgiving audiences than American voters—what they see is Trump

deploying tools and tactics that have worked before and could work again.

Before his campaign (calling John McCain

“not a war hero,” stating he could

shoot somebody and not lose supporters, boasting that he could “grab ‘em by the pussy”),

and before his presidency (the Mueller report, his impeachment, so much

of everything else over these last three years and not quite three months),

Trump had no shortage of experience doing things that could have spelled

doom—but did not.

He spent too much money that

wasn’t his on too much stuff he didn’t need. The Plaza Hotel. The airline. The yacht. And by the

early ‘90s it became exasperatingly clear to the bankers that Trump’s

debilitating issues weren’t just his. They were theirs, too. His creditors had

so enabled him that they were now “partners,” as a bankruptcy lawyer put it to

the Boston Globe. “Because he owed all this money,” his longtime

political adviser Roger Stone once said, “he had the leverage!” He had, thanks to

the banks, gotten bigger and bigger and bigger—until he was “too big to fail.”

For Trump, though, this was not an admonishment. It was a revelation. I’m

in trouble. But so are you. And so you can’t get rid of me now.

Ditto for the New Jersey gaming regulators.

Throughout the first half of the ‘90s, they could have stripped Trump of his

casinos, on account of his manifest lack of “financial stability.” The

assessments of Trump by the Casino Control Commission and the Division of

Gaming Enforcement were stark. The Trump Organization was “near insolvent.” His

“fiscal health” was “worrisome.” His casinos’ ability to obtain the necessary

credit and funds was “significantly diminished.” Trump, the division reported

to the commission, was on track to have personal income of $1.7 million in ’91.

Then $700,000 in ‘92. Then $300,000 in ’93. Trump was, the numbers made plain,

in the throes of financial death. “Unsettling,” understated one member of the

commission. In the end, though, the gatekeepers always gave Trump green lights,

granted leeway, extended deadlines. They cited his “progress,” which always was

more wishful thinking than defensible fact. They let Trump live because they

feared a dead Trump would lead to a dead or at least severely staggered

Atlantic City. “Too big to fail”—again.

What

played out around this time on Manhattan’s Upper West Side was

a version of the same. Trump had tried for years to put on a sprawling tract of

land that he owned a mammoth development anchored by the tallest building in

the world. He wanted to call it Trump City. But he was stymied by neighborhood

resistance and his own persistent spats with government officials. This

property, like his casinos, could have been a waterloo. Thanks, though, to

investors from Hong Kong, it proved to be the opposite. His grandiose vision

had to be ratcheted down to a more modest project, but the collection of

buildings (formerly) known as Trump

Place made the plot a moneymaker instead of a money loser. Here, too, Trump had

jimmied his way out of a tight spot, and with a product to promote.

“Donald is pretty fast on his feet,” Kent Barwick, who clashed

with Trump as the president of the Municipal Art Society at the time, told me.

“I mean, he may not be a Mensa candidate, but he’s shrewd.”

“The dodging and the weaving and the bullshit,” said Steve

Robinson, an architect involved in the Upper West Side resistance, recounting

Trump’s methods.

Indeed, Trump spent the first half of his worst decade not just

scrambling to survive but constructing a runway of rhetoric for what he

eventually was able to pull off with the IPO of ’95.

“What Donald Trump has done, essentially, is sell some assets and

reduce debt,” Trump wrote in 1991 in a letter to the editor in the Washington

Post. “Donald Trump is doing very well.”

The Taj filed for bankruptcy that year. The Plaza did the next

year. So did the Castle. It didn’t matter. Trump, undaunted and unabashed,

began hammering away about a “comeback.” And he didn’t do it on his own. He had

help. Because for all of the media’s harder-hitting, stacks-of-facts

chronicling of his failures, and for all the many occasions Trump disparaged

“sick” and “nasty” reporters who “should be ashamed,” journalists at times also

helped push his preferred version of himself. “He’s Ba-ack,” Business

Week said as early as 1992. “You’ve got to hand it to Donald Trump.

He’s one of the few shooting stars from the ‘80s who can boast of a comeback in

the ‘90s,” ABC News’ Sam Donaldson said on “Primetime Live” in 1994.

“I think

he is the world’s greatest promoter and P.R. person,” Wilbur Ross, who is the

Secretary of Commerce now but was a prominent investment banker then,

told Vanity Fair that year. “He has captured the public

imagination and turned it into a resource for himself. People may joke that

he’s always promoting himself, but he’s figured out a way to make it more than

an ego trip.”

Underwriters of the stock deal had promoted the sheen of Trump’s

well-known name and the sway it held with his typical day-tripping, relatively

small-sum customers. “Defying reason,” Forbes said that fall,

investors bit. “There’s a lot of brand equity in Trump’s name,” a stock analyst

told USA Today in November of 1995, “in middle America.” Trump

was quoted in the article, too. “The general public loves Trump again. They

really never stopped loving Trump,” he said.

Trump spun from the confidence of a certain portion of the

population money for himself. “The ’95 thing injected him with new cash,” said

David Cay Johnston, the Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter who covered Trump and

his casinos for the Philadelphia Inquirer and then the New

York Times, “and allowed him to argue that he was this great genius.”

That in turn allowed him in ’96 to fold into his publicly traded

company his other two Atlantic City casinos, first his Taj Mahal, then his

Castle. And maybe equally importantly, people buying what Trump was selling

let him buy time—time, it turned out, until 2004,

when television impresario Mark Burnett began

to re-pitch him to watchers of “The Apprentice” on

primetime as the epitome of American business brawn. Buffed and on screen,

Trump appeared to be an infallible, decisive CEO with a Midas touch past.

That catchy pop-culture depiction buried the much less flattering

reporting repeatedly laid out in the business pages of the biggest and most

mainstream newspapers and magazines. Gauged as a whole, Trump Hotels &

Casino Resorts was “a flop,” Shawn Tully of Fortune wrote in March of

2016, as Trump as a presidential candidate left in his wake the Republican

primary pack and began to take aim at Hillary Clinton. It

“damaged thousands of shareholders, bondholders, and workers.” Losers

everywhere. “The sole ‘winner,’” explained Tully, an experienced financial

scribe, “now packs arenas across America, mesmerizing tens of thousands of

cheering fans with tales of his business triumphs.”

Tales remains the operative term. Because

the contest at hand is not only between Trump and the ravages of Covid-19, or

Trump and “Democrat” governors, or Trump and any of the reporters spread out in

the seats in the briefing room these evenings at the White House. All of it is

part of the larger war for Trump between the numbers and the narrative. Will

this president, as has been the case with other presidents, be punished at the

ballot box for a woeful reality, not always of their making—or will enough of

the voters of 2020, like the investors of the mid-1990s, be susceptible to

Trump’s proven brand of brazen persuasion?

There are people I talked with for this story who side with the

implacable numbers. Death tolls and unemployment and impossibly long lines at food

banks, they say, simply can’t be swamped by even the most tenacious attempts to

scramble storylines.

“I am definitely in the camp of not this time,” said

political scientist Rachel Bitecofer, who

predicted with startling accuracy the results of the 2018 midterms. “Body

bags,” she said, leave “an indelible impression.”

“The Trump magic only works if he’s got gullible audiences, or at

least curious audiences,” said Mercieca. She’s the

author of the book due out this

summer about the “rhetorical genius” of Trump. But she still thinks this skill

set has its limits. “And if we’re really miserable in November and we may well

be very miserable, then I think people probably are going to associate that

with Trump.”

There are also, though, those I spoke with who believe Trump has

the capacity to cloak the numbers and recast them as positives, not

negatives—that he, in essence, totally could talk his way out of this by

telling a better story. Could Trump get reelected? In spite of a plague?

In the midst of wide-ranging economic devastation? These people all but sighed

when I asked.

“Yes,” said former Trump casino executive Jack O’Donnell.

“Yes,” said Tim O’Brien, the Trump biographer who’s a

columnist for Bloomberg Opinion and served as a senior adviser for Mike

Bloomberg’s presidential bid. “He is so uniquely pathologic and uniquely

remorseless, and I think it gives him this reptilian energy to continuously

deny, spin and move forward,” O’Brien continued. “And November’s a long way

off.”

O’Donnell, O’Brien and others see him doing what he did in those

years leading up to that spring and summer of 1995.

“Trump is a simple guy with a few basic moves,” former Trump P.R.

man Alan Marcus told me. “He always goes back to what’s worked in the past.”

“He’s obviously positioning himself for the long haul here,”

O’Donnell said. “For all his lack of knowledge about so many things, he’s

pretty darn media-savvy, and he’s working this right now almost brilliantly to

the extent that he realizes the value of putting himself out there every day,

and even if he doesn’t say the right thing every day, and even if he

contradicts himself, what he’s doing is he’s laying a framework to defend

himself. He’s spinning this every day now: 2 million would have died if it

wasn’t for me—and it’s pretty clear it’s not going to get to 2 million—so

whatever that number is beneath it, whether it’s 100,000 or 200,000, which is

just horrible, to him it’s a victory. And he’s going to present it as that.”

It’s what he’s done for decades, hawking these kinds of

alternative narratives—first and foremost the lie that he’s a

self-made man—and these narratives have been remarkably successful, and

protective, too.

“He also has been uniquely insulated from the consequences of his

own mistakes his entire life,” O’Brien explained, “first by his father’s wealth

that insulated him from his educational and then business mistakes; and then

celebrity, which insulated him from being forgotten, even though he was a joke

as a businessman at that point; and then this third ring of fire—the

presidency—which has insulated him legally from the consequences of his corrupt

behavior. And I would say there’s a likelihood that in 2020 he gets insulated

from being defeated because he’s able to make a pandemic a winner for himself.”

Many

people I talked with said Trump’s already turned this calamity into

opportunity, pointing to his nearly daily briefings, which by some

accounts are like his rallies only better—because they happen more often and

are watched by more people. Their efficacy is very much an open question.

Polling is showing the

benefits are fading, as the briefings have grown longer, less focused and more

contentious. Struggling with mounting coverage painting

him as a heedless, feckless ditherer who ignored numerous dire warnings, Trump

has stuck unwaveringly to a characteristic P.R. offensive, accepting no “responsibility,”

claiming “total” authority, and

presenting himself as an on-it and unassailable manager—putting his name on mailed-out CDC guidelines and stimulus checks while

relentlessly shifting blame for this “invisible enemy” to the

World Health Organization, China, states he says weren’t prepared enough,

governors he thinks don’t thank him enough.

“Never underestimate Donald Trump,” said Sam Nunberg, a Trump

adviser during the 2016 campaign. “He’s able to adapt to any situation.”

In the past, too, Trump stared down these existential threats with

small, sometimes seat-of-the-pants teams on the 26th floor of Trump Tower, not

as an incumbent president backed by a sweeping, sophisticated, funds-flush

reelection operation—his campaign and adjacent entities raised $212 million

in the first quarter and have raked in more than $1 billion

overall—well-equipped, ready and willing to fight these next six and a half

months on a narrowed, drastically altered front, a “virtual” campaign that

could be defined by screens and fear.

Come November, Trump could win again, say political strategists

associated with both major parties, not in spite of the coronavirus but because

of it.

“If I

was Brad Parscale,” Greta

Carnes, the national organizing director for Pete Buttigieg’s presidential

campaign, told me, referring to Trump’s campaign manager, “I would be

salivating right now, because this is the exact kind of

environment where Trump will do well.”

Anger, anxiety and an onslaught of misinformation online were

engines of Trump’s political ascent, and this unprecedented, disjointed general

election is shaping up to be rife with all three.

“This year is going to be so scary, so volatile, so anxiety-inducing,”

Carnes said, “I just think in my heart of hearts that it’s going to take a

really uphill battle for people to want to pick somebody else”—an extreme

version, perhaps, of what saved post-Sept. 11 George W. Bush in 2004, the

strong pull to not change course even during a deeply unpopular war.

Presumptive Democratic nominee Joe Biden “before Covid

actually had a better chance of being elected than he does now,” Rick Wilson,

an anti-Trump Republican strategist, told me. Wilson’s reasoning: Biden’s comparatively

absent from the national conversation right now—and Trump is making sure of it.

“Trump’s numbers depend in part on Trump absorbing all of the spotlight. We

learned this in ’16,” Wilson said, “and right now he’s absorbing all of it.”

Attention can be good or bad, but a central gambit of the life of

Trump is that that’s actually not true. That it’s all good. That attention is

power. That if you’re watching, he’s winning.

“Anybody who studies him and studies the nature of power and

propaganda when melded together should understand that this is not going to be

easy,” veteran Democratic strategist Hank Sheinkopf said of his party’s shot to

make Trump a one-term president.

“Americans are suckers for a good story,” he said. “Donald Trump

is going to give ‘em a good story.”

And that story is?

“The story is,” he said, shifting into the ominous voice of a classic political ad narrator, “the nation faced its greatest crisis since the Second World War. And we were led by a president who had been hobbled by people who had tried to destroy him from Day One.

The

economy was in tatters. Millions were out of work. What did Donald Trump do? He

did what all great American leaders have done. X, Y, Z. Now,

despite what we’ve been through, this most extraordinary nation, blessed by

God, is on its way back. It won’t be easy, but we’re going to get there,

because Donald Trump is leading the way.”

The video the president showed at the

beginning of Monday’s briefing that many described as propaganda marked an

escalation in this effort and a likely preview of what’s to come. “PRESIDENT

TRUMP TOOK DECISIVE ACTION,” the screen said.

And on Thursday, on the heels of the latest dismal unemployment

numbers, the Trump campaign blasted out an email, with a quote attributable to

its communications director, trying to flip the narrative. It echoed Sheinkopf’s

mock script. “Under the president’s leadership the economy reached

unprecedented heights before it was artificially interrupted and it will be

though his guidance that we’ll restore it to greatness …”

Don’t believe this can work?

Don’t believe Trump can win?

“Talk to

President Hillary Clinton,” Sheinkopf said.

Fact-checking Rump

Fact-checking Trump’s lies is essential. It’s also

increasingly fruitless.

By

Media columnist

August 29, 2020 at 6:00 a.m. CDT

Daniel

Dale met President Trump’s convention speech with a tirade of truth Thursday

night — a tour de force of fact-checking that left CNN anchor Anderson Cooper

looking slightly stunned.

The

cable network’s resident fact-checker motored through at least 21 falsehoods and misstatements he

had found in Trump’s 70-minute speech, breathlessly debunking them at such a

pace that when he finished, Cooper, looking bemused, paused for a moment and

then deadpanned, “Oh, that’s it?”

So, so

much was simply wrong. Claims about the border wall, about drug prices, about

unemployment, about his response to the pandemic, about rival Joe Biden’s

supposed desire to defund the police (which Biden has said he opposes).

Dale is

a national treasure, imported last year from the Toronto Star, where he won

accolades for bravely tackling the Sisyphean task of fact-checking Trump. My

skilled colleagues of The Washington Post Fact-Checker team, who recently published

a whole book on the

president’s lies, have similarly done their best to hold back the

tide of Trumpian falsehoods.

Dozens

of organizations, from Snopes.com to FactCheck.org and many others, are kept

busy chasing political lies, so many of which come from the current White

House. But here’s the rub. More than a decade after the innovative

Florida-based fact-checking organization Politifact.org won a

Pulitzer Prize, fact-checking may make less of a difference

than ever.

More

and more, fact-checkers seem to be trying to bail out an ancient, rusty and

sinking freighter with the energetic use of measuring cups and thimbles.

“My

biggest takeaway of the last four years is probably realizing the extent to

which big chunks of America are living in a different universe of news/facts

with basically no shared reality,” was how Charlie Warzel, who writes about the

information wars for the New York Times put it last week.

I

happened to be sitting in the WAMU studio in late 2016 when Scottie Nell Hughes

— then a frequent surrogate for President-elect Donald Trump and a paid

commentator for CNN during the 2016 campaign — said something startling, live

on the Diane Rehm radio show: “There’s no such

thing, unfortunately, anymore, (as) facts.”

Rehm

had pressed her about Trump’s false assertion that he, not Hillary Clinton,

would have won the popular vote if millions of immigrants had not voted

illegally. That was a claim he seemingly had heard on Infowars — the conspiracy-theory-crazed

site run by Alex Jones, who at one time claimed that the 2012 massacre of 20

children and six staff members at an Connecticut elementary school was a

government-sponsored hoax.

Hughes

gave not an inch of ground: Trump’s false claims, she insisted, “amongst a

certain crowd . . . a large part of the

population, are truth.”

Belief,

therefore, takes the place of fact.

The

situation has only become worse since then. And as scholars have observed,

calling out falsehoods forcefully may actually cause people to hold tighter to

their beliefs.

That’s

the “backfire effect” that

academics Brendan Nyhan and Jason Reifler wrote about in their study “When

Corrections Fail” about the persistence of political misperceptions: “Direct

factual contradictions can actually strengthen ideologically grounded factual

beliefs.”

Not

knowing what media sources to believe — and the growing mistrust in the press

among many segments of the public — has added to the problem of politicians who

lie.

Last

week, I was asked to settle a family dispute about the believability of a news

report that had been circulating on a group text-message chain.

One

family member (I’m being vague since I hope to continue to be invited to

Thanksgiving dinner) was outraged by the supposed revelations in a Newsweek

article whose headline read “Brand New Mail Sorting Machine Thrown Out at USPS

Center, Leaving Workers Sorting by Hand.”

Another

family member had serious doubts about whether this was true. He dismissed it

as “hearsay.”

And a

third asked me to take a look: Would I have published the article?

It

didn’t take me long to decide it wasn’t credible or publication-worthy.

Newsweek, despite its legacy name, is suspect from the start these

days. The article’s sourcing was thin. And a hyperlink, its main piece of

evidence, led me to a local news site that already corrected the main element

of its story. (Days later, Newsweek still hadn’t updated its story.)

These

family members care about the facts, and were engaged enough to be curious

about whether a report is accurate. And while it may have suited their politics

better if it were true, they were open to hearing that it

wasn’t.

But

most people don’t have the time or energy to do research projects on the news

they are reading, or the claims they are hearing from the White House, or the

conspiracy theories that flood their Facebook feeds.

Most

people no longer share with their fellow citizens the trust in news organizations

— or in political actors — that would give them confidence in a shared basis of

reality. And worst of all, the flow of disinformation on social media is both

vile and unstoppable.

In this

world, challenging official lies and seeking truth remains necessary, even

essential. The yeoman’s work of Daniel Dale, and others like him, remains

appreciated.

But I’m

with Warzel on this: As Americans, we’re in trouble when it comes to a common

ground of reality on which to stand.

And no

amount of fact-checking is going to solve that overwhelming problem.