When A.I. Took My Job, I Bought a Chain Saw

Dec. 28, 2025

By Brian Groh

Mr. Groh is writing a book about the disappearance of a man in Lawrenceburg, Ind.

Some of the best career advice I’ve received didn’t come from a mentor — or even a human. I told a chatbot that A.I. was swallowing more and more of my work as a copywriter and that I needed a way to survive. The bot paused, processing my situation, and then suggested I buy a chain saw.

This advice would have seemed absurd back when I lived in Washington, D.C., in a dense neighborhood of rowhouses. But for the past 25 years, I’ve lived in Lawrenceburg, Ind., a small, working-class town where my grandparents once ran a bakery.

After my widowed grandmother died, I wanted to be closer to family and to live inexpensively while I wrote a novel. So I moved into her empty farmhouse on a hill overlooking the Ohio River, several smokestacks and the modest grid of downtown. Taxes from a casino help keep our Main Street looking quaint. But beneath that appearance lies a dark, familiar story: After factory jobs disappeared, neighbors without college degrees began dying in disproportionate numbers. In 2017, as opioid deaths reached a record high nationwide, a local radio station, Eagle Country, reported that county residents were “taking their own lives at a startling rate.”

Preoccupied with my challenges and those of the people I cared most about, I rarely gave much thought to this crisis. For most of my adult life, I wrote nonfiction and novels, making ends meet as a freelance copywriter. I assumed I was protected from the outsourcing and automation that had left so many of my neighbors unmoored.

Over time, however, marketing departments began hiring contractors overseas for a small fraction of my rate. Then they turned to artificial intelligence, which could spit out something good enough — or even exceptional — in seconds.

Maybe I should have seen it coming. I had hired a woman in the Philippines to do transcription work, but once A.I. proved just as capable, I began using the transcriptionist less often, then not at all. When my own work was being replaced, though, I felt shocked and ashamed. I was like a factory worker who had watched manufacturing jobs disappear for years yet, after decades on a production line, still couldn’t believe that he, too, was being let go.

A new and disquieting thought confronted me: What if, despite my college degree, I wasn’t more capable than my neighbors but merely capable in a different way? And what if the world was telling me — as it had told them — that my way of being capable, and of contributing, was no longer much valued? Whatever answers I told myself, I was now facing the same reality my working-class neighbors knew well: The world had changed, my work had all but disappeared, and still the bills wouldn’t stop coming.

And so it was that one anxious night, after staring at the due date for my property tax, I asked a chatbot what it thought would be the best work for me, exactly the way — if I’d had more money — I might have sought help from a counselor: I explained my work experience, where I lived and how urgently I needed income.

Of the options it provided, cutting and trimming trees for local homeowners was listed as No. 1.

I asked if that was seriously my best option.

“Yes,” the bot wrote. “Based on your situation, skills and urgent need for income, tree work sales is almost certainly your fastest path to real money.”

It told me what equipment I’d need, where to buy it, which neighborhoods to canvass, what times of day to knock on doors and even the nearest landfills where I could drop off brush.

Never mind the irony of taking career advice from the kind of machine that was replacing me. I felt increasingly hopeful. I love being outdoors, and soon I discovered I loved the clarity of the work. Unlike with copywriting, clients could never ask me to do the job over in a different way. The dead tree they’d wanted gone was now gone. And seeing them happy, handing me money, always made me happy, too.

Every so often, in a client’s eyes, I thought I caught a flicker of condescension — the kind that confuses education with moral virtue and people’s income with their worth. But it didn’t bother me much. I’d been guilty of that perspective myself, and the more I talked with my neighbors, the more deeply I knew it was wrong. On good days, I earned more doing tree work than I ever had writing copy. And after decades of staring at a computer screen, moving only to peck a keyboard, it felt invigorating to cut through logs and wrestle branches, breathing deep lungfuls of open air.

At 52, however, I sometimes found the work challenging. When I began doing it full time last spring, I was often sore for days straight. I told myself that by stretching more in the mornings or perhaps investing in lighter equipment, I could make it sustainable. Gradually, a pain settled in one elbow: a dull ache when I gripped the chain saw.

One afternoon, while I was knocking on doors, a man stepped onto his porch, shirtless, and pointed to the Bradford pears in his yard. “I paid an old friend to cut these trees,” he said. “He did a little, but then he killed himself.”

In that moment, I saw before me — with an inner tremor — the path that too many of my neighbors had taken. Without steady, decently paying employment, they took on physically demanding day labor, got hurt, relied on painkillers and slid into a downward spiral.

My chatbot, with its relentless optimism, had failed to mention this possibility. When the pain in my arm made it impossible to work a full day, I often found myself in my living room, scrolling for jobs on my phone. For years, politicians and pundits had told displaced factory workers to retrain and adapt. I’d done that once already, and now, if I didn’t heal soon, I’d have to try something else. I like to think of myself as an optimist, but at night, kept awake by the throbbing in my arm, I sometimes wondered: What new skill should I spend months — maybe years — learning? And how long before A.I. could do that, too?

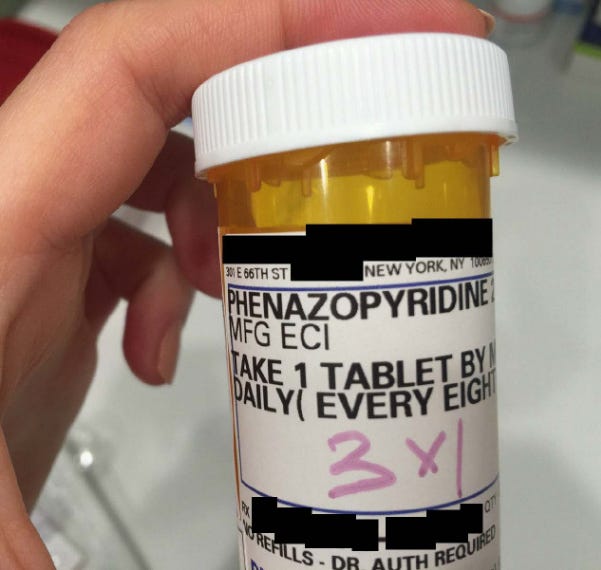

My arm still hasn’t healed. And recently while tearing out roots, I badly injured my back. A neighbor offered me prescription painkillers to help me get through the work. And I’m writing this, at least in part, to resist taking more of them. Even when I recover, I’m not sure how long this solution will last. I hope I’ll be able to get back to cutting trees for longer hours. But I suspect I’ll soon face increasing competition, as many people — especially recent college graduates — look for ways to make money that A.I. can’t yet replace.

In towns like mine, outsourcing and automation consumed jobs. Then purpose. Then people. Now the same forces are climbing the economic ladder. Yet Washington remains fixated on global competition and growth, as if new work will always appear to replace what’s been lost. Maybe it will. But given A.I.’s rapacity, it seems far more likely that it won’t. If our leaders fail to prepare, the silence that once followed the closing of factory doors will spread through office parks and home offices — and the grief long borne by the working class may soon be borne by us all.